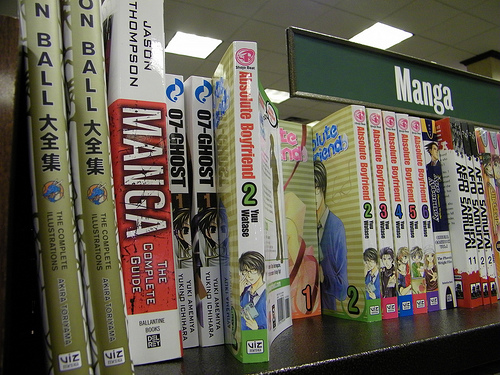

Walk into a Barnes & Noble, Borders, or almost any other American bookstore, and you are certain to find a section labeled “Manga.” Often two or three times the amount of shelf space devoted to the comics of the United States is given over to the small thick booklets filled with Japanese drawings. Why have the adventures of aspiring ninjas and timid schoolgirls taken over displays once devoted to Superman and Captain America? For the stores stocking manga the answer is simple: economics.

In 2007, Publisher’s Weekly reported the previous year’s sales figures for graphic novels in the United States and Canada. The results were staggering. The comic stories were worth approximately $330 million, with manga making up $170 – $200 million of that total.1 Manga made up better than half of the total graphic novel profit, and additionally there were simply more titles published. In the same report Publisher’s Weekly noted, “There were about 2,800 book format comics published in 2006, up 12% from 2005. Out of that total, 1,200 are manga titles and 965 are American genre comics.”1 With these numbers increasing every year manga is both more prevalent and more profitable in the United States – something that bears a stark contrast to its success in its home nation.

Even as Publisher’s Weekly reported manga’s success in the United States, USA Today reported the troubles it faces in Japan. “Sales of manga fell 4% in Japan last year to 481 billion yen ($4.1 billion) — the fifth straight annual drop, according to the Tokyo-based Research Institute for Publications.”2 Citing the prevalence of cell phones, video games, and a lack of variety in the comics for the decline, the article nevertheless concludes with a quote from Tufts’ Professor Napier, “They [manga] are still a staple of Japanese life.”2

This raises the question of why this struggling Japanese staple is making such a huge splash in the United States. What is it that has attracted Americans away from their own comic culture and drawn them to one so different? The first answer to this question lies precisely in that difference. When Roland Kelts interviewed Studio Ghibli Director of International Relations Steve Alpert, he asked what first attracted him to the Japanese style. Alpert replied “The way they used the frame – they weren’t afraid to break it… The perspectives are so evocative.”3 Kelts similarly writes of the works of Osamu Tezuka as “the beginning of what is referred to today by… Matt Alt as ‘the Mobius Strip’ of interrelations between Japanese and American artists – a crosspollination of influences.”3 Thus manga provides American audiences with a visual medium that initially seems extremely different, yet has been consistently and heavily influenced by their own culture.

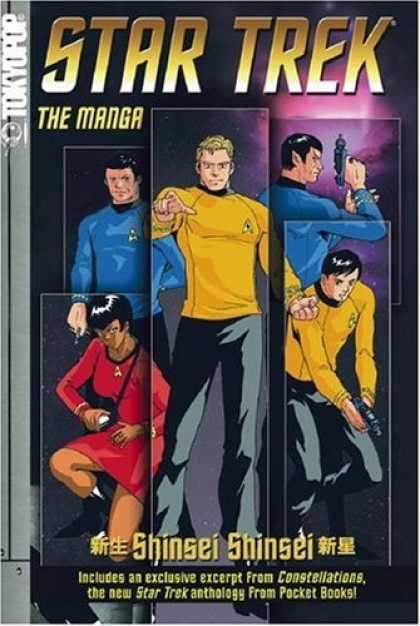

This combination has allowed Americans to enjoy manga as an inherently “cool” other. Kelts notes, “Even the manga that is translated into English today retains certain Japanese phrases and writing in the native characters – undecipherable and illegible to most U.S. readers, but still considered cool.” This tendency can be seen in its extreme in the publication of American stories in manga form. Multiple Star Trek series have had new stories published in manga form, and even the classic Canadian superhero Wolverine has garnered his own manga. Therefore, manga is at once familiar and alien to Americans. Its otherness is exotic, cool, and comfortable – and so it sells.

In his article “A History of Manga,” first published in Viz Media’s Animerica: Anime & Manga Monthly, Matt Thorn similarly cites Tezuka’s work as one of the great turning points for the sale of manga. “Tezuka’s innovations led to a broadening of the manga market and had a consequence that would inevitably force a radical restructuring of the market: the children who were raised on the manga of Tezuka and his followers, unlike their predecessors, didn’t stop reading manga when they got to middle school. Or high school. Or college.”4 What happened in Japan decades ago has now happened in the United States. This training of the American consumer goes fundamentally against traditional American perception of comics as children’s reading. In the U.S. traditional times to outgrow comics – high school, college – have become essential growth times for American interest in manga. Entire websites such as www.bleachexile.com and www.onemanga.com are devoted to providing English language access to manga – sometimes releasing translations months, even years, ahead of a U.S. print release. Manga keeps its cool long after other comics have been left behind.

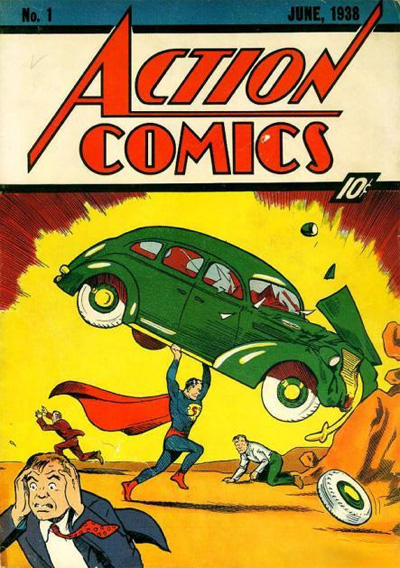

One of the problems plaguing manga at home has become a great strength for it in the United States. As reported by USA Today, Japanese consumers are “bored with the plots and characters manga offers.”2 Yet these same plots and characters that are old hat to Japanese readers are totally new to Americans. American comics, in contrast, have trouble breaking out of their own set ways. Superman was created in 1932, and though he has had many new adventures since then, the character has remained essentially the same. Thus although the adventures of Naruto and Rurouni Kenshin (both enormously popular series in both countries) may bear strong similarities to other titles, they are new stories, new heroes, and from a new land.

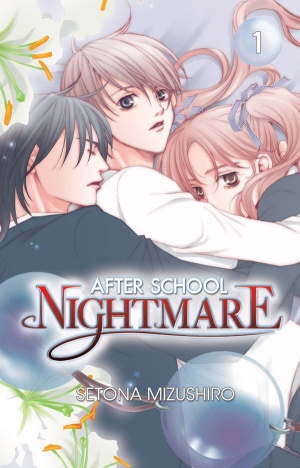

Further, manga has managed to captivate a segment of the United States market never truly captured by American comics: girls. An entire “shôjo” genre “which is created primarily by women artists explicitly for audiences of girls and young women” has quickly drawn in American girls.4 As Barnes & Noble buyer Jim Killen told USA Today, “Manga offers something they weren’t finding in popular superhero-related comics.”2 With an entire genre devoted to their interest, completely apart from American comics, it is no wonder that American girls have been drawn to manga.

Thus, in the United States manga has captured a large market because it appeals to readers on multiple levels. Telling new stories in new ways, telling stories specifically for girls, and keeping consumers interested beyond their grade-school days have allowed manga to become a cultural juggernaut, now inarguably a part of American youth culture.

Discussion Questions:

Manga is clearly a comic form like American comics, but it is also its own distinct tradition. How does the “mobius strip” factor into Japanese and American understandings of manga? To what extent is manga otherized by Americans? Is American produced manga valid, and if so does it have an American or Japanese cultural odor? Does any manga have a cultural odor?

Sources:

- Reid, Calvin. “Graphic Novel Market Hits $330 Million.” Publisher’s Weekly 23 Feb. 2007 Web. 4 Apr. 2010. <http://www.publishersweekly.com/article/391509-Graphic_Novel_Market_Hits_330_Million.php>

- Wiseman, Paul. “Manga Comics Losing Longtime Hold on Japan.” USA Today 18 Oct. 2007 Web. 4 Apr. 2010. <http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2007-10-18-manga_N.htm>

- Kelts, Roland. Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. Print. p. 24, 33, 42. <http://www.amazon.com/Japanamerica-Japanese-Culture-Invaded-U-S/dp/140398476X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1272007034&sr=8-1>

- Thorn, Matt. “A History of Manga.” Animerica: Anime & Manga Monthly. vol 4. 2, 4, 6. rev. 2007 Web. 4 Apr. 2010. <http://www.matt-thorn.com/mangagaku/history.html>

Entry contributed by Charles Fliss

Charles,

This essay is extremely informative for me, especially as I know very little about the Manga and it’s success in the United States. I found your information about the appeal that Manga has towards females in the United States particularly interesting. I was wondering if you think it could be possible for an American comic books to adapt and add a genre equivalent to the “shôjo” genre? Is it too late for American comics to try and recreate their image to be more female friendly?

Thanks Charles.

It sounds true that the Manga plots are old to Japanese but new to American readers. Do you think Manga became less attractive to American readers when the plot become old to them? Do you think they will get bored soon? I wonder how Manga can survive in America.

Max,

I think American comics have tried to create female interest, in a manner similar to the “shôjo” genre, but have largely failed. I see most “spin-off” heroines (Spider-Woman, Batgirl, etc) as such attempts. What I feel makes “shôjo” really unique is the kind of stories it tells. Batgirl’s adventures are essentially no different than Batman’s; she runs around beating up and otherwise thwarting bad guys. The stories in “shôjo” comics, by contrast, frequently focus on romance, school, or things that in American comics might seem more mundane. In an American comic, for example, romance usually complements action, while in a “shôjo” story it is more likely that the action serves to complement the romance. Can American comics figure this out and write these stories? I think they most certainly can, but I’m not convinced as to how much success they would actually have marketing it. “Kawaii” is not exactly one of the traditional traits of DC comics!

Sanami,

I think that Americans may eventually get tired of manga plots, but I think it will take a long time. It has taken nearly forty years for Japanese to get tired of manga stories, and manga has not been widely available in the U.S. for nearly that long. I think manga may be able to build a lasting fan base in the United States in ways that have not been widely accepted in Japan, specifically the growing cos-play and convention communities.