By Riki Saltzman, Folklore Specialist and retired Executive Director

When I started at OFN in the spring of 2012, I didn’t know much about Oregon, and I found that there hadn’t been a lot of recent fieldwork to identify and document folk and traditional artists. Under OFN’s then program manager, Emily Hartlerode (acting director), OFN had a Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program, which lent itself to documenting the master artist culture keepers who were entrusted with passing their cultural traditions to apprentices. And there was some collaborative work with Oregon’s Tribes in process. These were both great ways to document at least some of our state’s traditional knowledge and skills. But OFN needed to get to some deeper and more community-based work to fulfill its role as the state’s designated folk & traditional arts program.

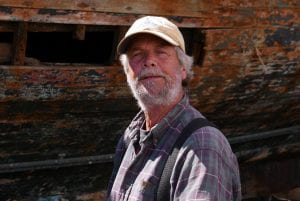

Knute Nemeth, commercial fisherman and marine storyteller. Photo, Douglas Manger

OFN’s operational partners—the Oregon Arts Commission, Oregon Cultural Trust, Historical Society, Oregon State Library, Humanities Oregon, and the Oregon Heritage Commission—agreed that starting a comprehensive, years’ long statewide folklife survey was the way to go. I’d learned in my nearly 18 years as Iowa’s state folklorist and in public folklore positions in several east coasts and southern states that research should drive public programs. Bess Lomax Hawes, the long-time director of the NEA’s Folk & Traditional Arts Program, always emphasized that there was no substitute for fieldwork. Getting out there to talk to communities—from those who have been here since time immemorial to those whose ancestors had come in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, to the newest of twenty-first-century immigrants—was the best way to learn who the culture keepers were and what their and their communities’ needs might be. Chris D’Arcy, then ED for the OAC and the OCT, recommended that we start with the most underserved and undocumented counties in southern and eastern Oregon: Klamath, Lake, Harney, and Malheur. We talked to folks in the Klamath Tribes and the Burns Paiute Tribe as well as county cultural commissions, historical societies, and local arts organizations. And we looked at census data to determine the cultural background of residents, their occupations, and the local natural resources likely to result in particular kinds of folklife. We also consulted the records of the former Oregon Folklife Program, now digitized at UO SCUA. And then we applied for NEA funding to hire independent folklorists to identify and document those traditional artists who would drive our programming.

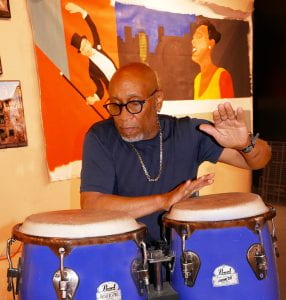

Jardin Kazaar (African American chef, nurse, storyteller, and musician) plays conga drums. Photo, Douglas Manger

Between 2013 through 2022, we’ve documented well over 400 tradition keepers. The many folklorists we’ve hired over the years (LuAnne Kozma, Douglas Manger, Joe O’Connell, Debbie Fant, Nancy Nusz, Makaela Kroin, Alina Mansfield, Amy Howard, Thomas Grant Richardson) have introduced us to so many incredible Oregon artists, many of whom have taken part in TAAP and public programs in their own communities and Tribes as well as in Salem, Bend, Ontario, and elsewhere. Over half of those interviewed have become part of the Culture Keepers Roster, which enables libraries, arts and cultural organizations, museums, festivals, and schools to access and hire some of the over 250 culture keepers for their programs. OFN’s Culture Fest Partnerships provide yet another way to promote Oregon’s diverse traditional cultures and provides funded partnerships with cultural organizations and Tribes to feature rostered artists—from cooks, saddle makers, quilters, Native basket makers and bead workers, to coopers, Persian storytellers, folklórico dancers, fisherpoets, and more—for public programs.

Storyteller, Andrew “Drew” Viles (Siletz), weaves baskets and gayu (baby baskets). Photo, Douglas Manger

OFN’s mission also includes educating the next generation of folklorists for which we partner with UO’s Folklife and Public Culture program. One of my great joys has been taking students on fieldtrips with our independent folklorists who provide mentorship in best documentation practices. Students have listened to hair-raising accounts from Columbia River Bar pilots (one of the most dangerous jobs in the world) and learned how to ty flies from anglers, how quilters select fabrics, and how sheep farmers also shear, clean, card, weave, and knit the wool from their own animals. They’ve also experienced witching for water, bidding for pies at a community fund raiser, documented rodeo and cemetery stone carvers, and so much more. Our independent folklorists have been incredibly generous with their knowledge as they introduce emerging folklorists to a vast array of Oregon culture keepers.

Lisa J. Taylor is a machine quilter. Photo, Douglas Manger

And then life changed with the pandemic. For the past two years, OFN, like so many organizations, has had to pivot to virtual activities. And I’ve ended up being the one to document culture keepers on Oregon’s south coast (FY21) and this year (FY22) in southern Oregon’s Douglas, Josephine, and Jackson counties and the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians. Virtual fieldwork starts the same way as in-person—with the demographic data and with press releases, emails, and phone calls. But it also does not include in-person visits, which limits photo documentation as well as long conversations. And not everyone has access to a strong enough signal to make a zoom interview possible. Despite drawbacks, there have been high notes, and I’ve been thrilled to be able to conduct several interviews this past year with quilters and fishing guides as well as a Hawai’ian hula kumu (teacher), ballet folklorico director, basket weaver from the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, stone wall builder, and a Kalapuya drummer, artist, and storyteller. While this kind of fieldwork is not the same as in-person, and I don’t get to drive all over this beautiful state, I do have the opportunity to learn about traditional Mexican musical instruments from a mariachi band leader in Talent and the holistic approach of a vaccaro-style rawhide braider and saddle maker outside of Roseburg. And on days when I’m dragging, there is always the uplifting feeling that I experience when those I’ve been talking to thank me for listening.

Homemade bagels by Stacy Rose, culture keeper of traditional Israeli foodways and folk dance. Photo, Douglas Manger

Instruments of Bob Shaffar, old time, blue grass, and western swing fiddle player and fiddle repairman. Photo, Douglas Manger

I always end an interview by asking people why they do what they do. It’s never about the money; instead, it comes down to their passion for their traditions and cultural heritage, about how they have to do what they do. Whether I’m talking to a steelhead fly-tier and one-time Umpqua River fishing guide, a seamstress who designs and sews both folklórico and quinceañera dresses, a Siletz baby carrier weaver, or an old time musician–it’s always an honor to hear their stories and learn how they continue to keep their cultural heritage alive, which sustains not only the individuals but also their communities and Tribes.

An extraordinary accomplishment under the leadership of Emily West Hartlerode and Riki Saltzman, current and former OFN directors.

Douglas Manger

HeritageWorks