A new approach: Lane County’s efforts to find effective solutions to sex trafficking

For the past year, Lane County has been developing a multidisciplinary team to combat sex trafficking under a statewide push to respond to the elusive problem. [Photo via kidsfirstcenter.net]

By Aubrey Bulkeley, Sydney Dauphinais and Isabella Garcia

An arsonist sets fire to your house, then you get arrested for letting it burn down. That’s how police in Oregon used to treat people being prostituted by sex traffickers.

But now, Oregon is currently in a statewide push to address sex trafficking—defined as the coercion of children and adults to perform commercial sex acts against their will—in a survivor-informed approach. Instead of stings to arrest people being prostituted, police are developing investigations to catch pimps and traffickers. Instead of adding another charge to a trafficked person’s criminal record, survivor support organizations are finding ways to interrupt cycles of abuse and help survivors out of the life.

Lane County is one of 11 counties joining the statewide effort to develop effective responses to sex trafficking. Funded by the Oregon Department of Justice, the Lane County Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children Multidisciplinary Team is an emerging network of agencies aiming to provide resources and support to survivors.

Sex trafficking is difficult to address because of its chameleon-like nature. Sitting at the intersection of sexual assault and domestic violence, trafficking can often look like other forms of abuse and be mislabeled, and mistreated, by professionals because of a lack of training about the signs of trafficking. Trafficking can also create intense psychological bonds between trafficker and survivor stemming from traumatic experiences and a survivor’s dependency on the trafficker to survive, which can be manipulated and used to keep survivors from reaching out for help. In other cases, survivors might not even recognize that they are being trafficked because their experience doesn’t reflect the dramatic depictions of trafficking they’ve seen in the media due to a lack of accurate public awareness.

This complicated entanglement of challenges and educational shortcomings is why Oregon is using a multidisciplinary approach in its statewide efforts.

Multidisciplinary teams are a network of organizations that provide varying resources and expert services to support survivors. The executive directors of Sexual Assault Services and the Kids’ FIRST Center, two survivor support organizations in Eugene, established the beginnings of the Lane County sex trafficking multidisciplinary team in 2017, allowing the team to receive funding from the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA), the federal grant attached to the statewide push for combating trafficking.

Once the Lane County team was approved for the three-year grant in April of 2018, Tamara LeRoy, the multidisciplinary team lead, was brought on to develop a network of organizations. LeRoy is currently working through the beginning stages of solidifying that network.

“What we’re doing is laying the groundwork and foundation for these [responses to trafficking] to be incorporated into the bureaucratic system and the agency protocols as we move forward,” LeRoy said.

Laying the foundation means resource mapping—identifying existing organizations within the county that can provide a service to survivors. The task isn’t a simple phone call to local agencies asking if they want to sign up for a call tree, but rather a long process of developing the way in which the agencies work together and rely on each other to most effectively help survivors out of ‘the life.’

Currently, the team is comprised of stand-alone organizations like Sexual Assault Services, Kids’ FIRST and Looking Glass, as well as government agencies like the Eugene and Springfield Police Departments, Department of Human Services and Welfare, and the Lane County District Attorney Office.

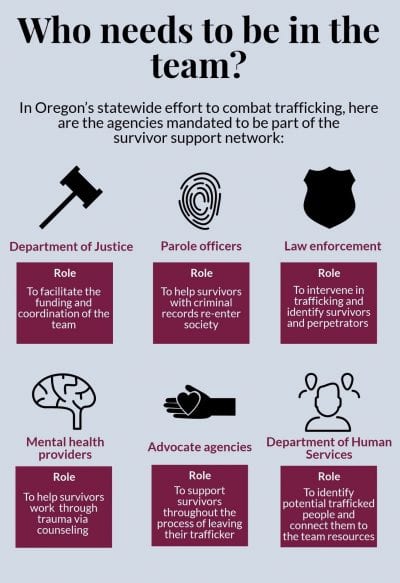

The agencies included in the network are chosen by what services the survivors of a specific county require, what organizations are available in the county and the agencies that are required to include in the multidisciplinary team, as mandated by the state. The agencies that need to be involved in order for a team’s basic bases to be covered are an advocate agency, the Department of Justice office, law enforcement, the Department of Human Services, parole officers and mental health services providers.

These agencies required for a multidisciplinary team to form have been identified through trial and error, with much of that trial and error happening in Multnomah County, Oregon’s first county to form a collaborative effort to combat sex trafficking. The state has since used Multnomah County as a model, including hiring Oregon’s statewide trafficking intervention coordinator, Amanda Swanson, from the county.

These agencies required for a multidisciplinary team to form have been identified through trial and error, with much of that trial and error happening in Multnomah County, Oregon’s first county to form a collaborative effort to combat sex trafficking. The state has since used Multnomah County as a model, including hiring Oregon’s statewide trafficking intervention coordinator, Amanda Swanson, from the county.

Swanson has been working on the shift in Oregon’s sex trafficking intervention from the beginning, starting as one of the first case workers for the Multnomah County collaborative in 2009. After helping develop 11 multidisciplinary teams with a couple more in the works, Swanson has learned the importance of distinguishing clear roles within the collaborative effort.

“It takes a lot of understanding one another’s position,” Swanson said. “Law enforcement is there to recover the victims and get the bad guys, because somebody needs to get the bad guys. The DA is there because they need to prosecute—that’s their job. The DA is not the one the survivor is going to call at 2 a.m. because they’re having PTSD or they’re being triggered, just like the advocate is not the one that’s going to be able to arrest the bad guy or prosecute them.”

There is a dedicated reason that each organization is part of the network: to provide medical services, to pursue legal action, to advocate for the survivor’s wellbeing, to influence the change of related laws and so on. That’s what makes the approach effective.

“There’s all these different puzzle pieces and when they are staying in their role, they come together beautifully, but it does take a lot of time and energy,” Swanson said.

As LeRoy, the Lane County team lead, continues to map the resources available to survivors in the county, she is looking for gaps in the services provided and how to mend them.

One gap in Lane County’s developing network is the lack of emergency housing that can be provided to survivors. It has been well-documented that traffickers control the people they traffic by maintaining control over their finances and, by extension, their living situation. A successful way to interrupt that control is to provide survivors with safe housing or money for rent. But the multidisciplinary team can only connect survivors to preexisting services within the community.

Because Lane County lacks an agency that provides emergency housing, LeRoy and the team cannot provide that service to survivors.

“The multidisciplinary team itself doesn’t provide anything, it’s just a network,” LeRoy said.

Another gap is that professionals who unknowingly interact with people being trafficked often don’t know what to look for and how to report a possible instance of trafficking.

“There’s lots of information about what trafficking looks like, but a lot of it is misinformation or disinformation or incomplete information,” said LeRoy. “There hasn’t been a lot of formal training available for people to understand.”

Trafficking situations often look a lot like domestic violence and can be mislabeled when survivors encounter professionals who have the power to help. A 2016 study by University of Kansas professors and medical professionals reported that at least 50 percent of trafficked individuals encountered health care providers while they were being exploited. If those health care professionals had the training to recognize the signs of trafficking and communicate resources to potential trafficked people, those survivors could have been provided an opportunity to leave their trafficker much earlier.

LeRoy hopes to establish a training program with Planned Parenthood and Lane County Public Health to better prepare medical professionals for how to recognize and work with survivors, as well as creating a reporting process for data collection. The Springfield Planned Parenthood has taken action in response to working with LeRoy and the team, reaching out to the national organization to set up a training program.

LeRoy has also found success with her role as a certified confidential advocate, meaning that she is not required to report to law enforcement when she observes or suspects abuse. This position allows her to speak honestly with survivors in a way that does not place blame or judgement on them. LeRoy is able to learn about a survivor’s situation and identify how to best help them, which often includes helping the survivor secure their safety prior to involving law enforcement.

Helping a survivor move forward at their own pace is essential to actually removing them from the life of trafficking.

“There’s research that shows if anything is mandated or pushed upon somebody, they are less likely to internalize it,” Natalie Weaver, sex trafficking program strategist for the Multnomah County Department of Community Justice, said. “What we find is, across the board, if someone is not in a state where they’re ready, then trying to force anyone to do anything doesn’t work.”

Forcing a survivor to leave their trafficker can have the opposite effect, sending them right back into their trafficker’s arms. One way this happens is through a psychological phenomenon called trauma bonding. Psychologists have found that when an abuser makes a survivor fear for their life, over time the survivor becomes grateful for their abuser allowing them to live. The severe power imbalance and erratic fluctuation of positive and negative interactions can create an intense bond for the survivor to their trafficker. This bond can prevent survivors from being able to accept help from outside sources and maintain the trafficker’s power over a survivor. It’s also the reason that survivors are manipulated into returning after an attempt to exit the trafficking situation.

This intense bond is also why survivors need to be the ones seeking a way out. LeRoy has found through interviewing survivors that it’s crucial to not be another person that is controlling their life, but instead act as an optional exit ramp.

“In our advocacy for trafficking survivors, we create a pathway for them to exit if that’s what they want to do,” LeRoy said. “I don’t advise people what to do or what not to do. If they come and they want to make changes to how things are going, then I direct them to resources.”

Empowering the survivors through education is often a crucial first step for building an exit strategy. People may not know that they are in a trafficking situation until they hear another story about it on the news, online or in an awareness-boosting community workshop and are able to draw parallels to their own experience. LeRoy believes that awareness is an effective deterrent for trafficking.

“Once they can put that label on for themselves, then they’re able to engage resources and they find their way to our office,” says LeRoy. “That’s been more of a slow trickle, but we do have traction in the community now, so we do have survivors who are coming and identifying as being trafficked and looking for support.”

Looking forward, it’s unclear if the Lane County multidisciplinary team will develop into a self-sustaining collaborative effort, but that’s Swanson’s goal for all of the participating counties.

“We are taking our time because we want to do this right, we don’t want to just be reactionary,” Swanson said. “We’re changing systems, we’re changing the way we’re approaching this issue and doing that takes a lot of time. It’s a slow process, but we’re doing it and overcoming a lot of obstacles, but it’s definitely not going to happen quickly.”

Outside of the Multidisciplinary Team

Survivor-centered organizations, outside of the county’s federally-backed network, speak to survivor experience

Survivors of sex trafficking return to their traffickers an average of five to seven times before leaving the life for good. Listen to Diana Janz, first voice and founder of Hope Ranch Ministries, and Amy-Marie Merrell, Portland director of The Cupcake Girls, speak to the need for providing ongoing support to truly help survivors escape the life.

Hope Ranch is a nonprofit organization founded by Diana Janz to support women and girls being trafficked in the Eugene-Springfield area. The organization develops personal relationships with survivors and provides emergency support, like transportation to a paid motel room for the night, as well as ongoing services that help survivors reintegrate into the Eugene-Springfield community.

The Cupcake Girls is an organization that specializes in providing support to people involved in the sex industry and those affected by domestic sex trafficking. The group, originating in Las Vegas before expanding to Portland, regularly visits strip clubs to provide services to, and build relationships with, workers. Due to the increase in strip clubs per capita in Lane County, The Cupcake Girls is looking to expand their operation into Springfield.