This week, the main new computational topic is complex eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Sage finds complex eigenvalues / eigenvectors by default, so we already know how to find complex eigenvectors:

A = matrix([[1,-2],[1,3]])

A.eigenvalues()

A.eigenvectors_right()

Note that Sage uses “I” to stand for i, the square root of -1. (This choice is because “i” is often used as an index, as in “for i=1…5”.) Manipulations work as you would expect:

I^2

z=2+3*I

z

z^2

z+z

Sometimes you want to extract the real part or the imaginary part of a complex number:

z

z.real()

z.imag()

The norm of a complex number a+bi is sqrt(a^2+b^2). Sage (reasonably) calls this the “absolute value”:

z.abs()

The complex conjugate of a+bi is a-bi.

z.conjugate()

We can check some identities, like:

bool(z.abs() == sqrt(z*z.conjugate())

bool(z.real() == (z+z.conjugate())/2)

(The “bool” means we want to know if the expression is true or false, i.e., we want a “boolean“.)

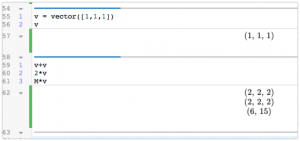

Some things work the same for vectors:

v=vector([1+I,2+3*I])

v.conjugate()

v.real()

Hmm… v.real() didn’t work. We can get around this by using the identity above:

(v+v.conjugate())/2

Another way is to use a bit more Python:

vector([x.real() for x in v])

You can also use exponential (or polar) notation for complex numbers. Use exp(x) for e^x. So:

exp(pi*i)

exp(2*pi*I)

4*exp(pi*I/4)

If we want to convert rectangular representations of complex number to polar ones, we already know how to get the length, with z.abs(). The angle is the argument, so use arg(z). (Why this isn’t z.arg() is a mystery to me.)

arg(z)

arg(i)

arg(1+I)

arg(1+sqrt(3)*I)

As you’ll notice, Sage is remarkably bad at doing this symbolically: it just sort of throws up its hands at 1+sqrt(3)i, where we (of course) know the answer is pi/3. You can always get it to give you a numerical answer, by typing:

float(arg(1+sqrt(3)*I))

We can even torture it into admitting that this is pi/3:

bool(float(arg(1+sqrt(3)*I))==float(pi/3))