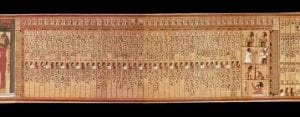

The scales of Ma’at

In Egypt: Ancient History of African Philosophy, Théophile Obenga argues that African philosophy, or more specifically, Egyptian philosophy has been wrongfully excluded from philosophical canon, and more than simple inclusion, the study of Ma’at ought to be one of the most respected and well taught schools of philosophical thought.

One of the first issues Obenga approaches is that Egypt has been considered something other than African historically, either being considered the Near-East or Sub-Asian. The author doesn’t expressly address that the reason for this omission of Egypt as African was to justify the viewing of African people by Europeans as being lesser, while simultaneously being in awe of the Egypt’s progress as a civilization, though I’m sure in that debate he would have a more nuanced and vehement argument than I just gave.

Obenga goes on to express that in his view (though the essay is presented entirely as facts not up for debate) the first use of a word equivalent to philosopher was used in Egypt and written in hieroglyphics. He then spends several pages describing the form and meanings of many hieroglyphics while attempting to convince the reader that hieroglyphics are the only, best, and most effective way to convey meaning; for example, the symbols for “mouth”, “placenta”, and “papyrus, rolled up, tied and sealed” when combined mean “to know”. Get it?

I feel that if the essay were written by someone else or written as if it were a theory up for debate rather than a declaration of truth or a polemic against the prevailing academic thought of the time I would be far more likely to find it somewhat convincing. The central point that studies of philosophy have been euro-centric is absolutely true, the idea of philosophy very likely came about with the growth of city-states wherever they rose, including Egypt, but claims such as Egypt having no jails or social distinction between men and women for 35 centuries because of the power of Ma’at is too unbelievable and discredits the rest of Obenga’s work. (Not to say jails and social distinction among genders is innate to humans, but that’s another discussion for another time).