Learn @ the DREAM Lab Learning Resources

Copyright, Fair Use, and Licensing: A Guide for Researchers

Copyright, licensing, and fair use can be overwhelming and confusing while creating and disseminating research. This educational resource is meant to guide the University of Oregon’s research community to understand and navigate copyright complexity and empowered in making decisions in their research.

What will you find here?

The information included in this resource is for UO researchers who want to learn more about the ins and outs of copyright law and best practices when doing research.

Topics include:

- Where to find help at the University of Oregon

- Foundations of copyright, licensing, and fair use

- Foundations of public domain

- Introduction to open licensing

- Find copyright free and openly licensed materials for research (images, videos, documents, tabulated datasets, and sound recordings, etc.)

Defining Copyright

Copyright is the collections of rights related to ownership. It automatically gives an author of creative works like literacy works, photographs, songs, movies, and softwares control the rights over how the work is shared and reused.

U.S. copyright law is referred to in the Constitution, where Congress is given the power “to promote progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries,” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 8).

Though it has been revised and updated several times, most recently in the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the core rights given to creators have essentially remained the same:

- To reproduce the copyrighted work in copies

- To prepare derivative works, such as translations, dramatizations, arrangements, versions, etc.

- To distribute copies to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, such as licenses, contracts, etc.

- To perform the copyrighted work in public

- To display the copyrighted work in public

What is protected by copyright?

All original, creative works fixed in a tangible medium of expression may be protected by copyright. Copyright protection does not require publication or registration of the work with the U.S. Copyright Office. It is applied at the moment a creative work appears in fixed form. Nor are works created after 1978 required to display a © symbol.

However, registration with the Copyright Office has some advantages:

- It establishes a public record of the copyright claim

- In order to sue for infringement, a copyright claim must be registered

- Registration may be completed at any time during the life of the copyright, but registration within three months of the date of creation entitles the owner of the copyright to statutory damages and lawyers fees

What is not protected by copyright?

There are a number of areas that are not addressed by copyright law:

- Non-fixed works. To receive copyright, a work must be “fixed in a tangible medium of expression”. If it’s not, it doesn’t get a copyright.

- Ideas. From U.S. copyright law: “In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.”

- Facts. Works consisting entirely of information that is commonly known and containing no original authorship are not protected by copyright. This could include calendars, height and weight charts, tape measures and rulers, etc.

- U.S. Government Works. From U.S. copyright law: Copyright protection “is not available for any work of the United States Government.” This could include federal judicial decisions, statutes, speeches of federal government officials, press releases, census reports, etc.

- Lots of other things! There are many other things specifically not protected by copyright, including cooking recipes, fashion designs, titles and slogans, domain names, band names, genetic code, and “useful articles” that have a utilitarian function (like a lamp).

Copyright & Licensed Content

What is a copyright license agreement?

A copyright license agreement is an agreement upon which a copyright holder determines what permissions are given to share and reuse a creative work.

Where do researchers typically encounter copyright agreements?

- Publishing books, journals, and other creative academic works

- Working in special collections and archives

- Reusing published research data

- Becoming a work for hire

- University proprietary rights agreements

- Licensed publisher content found in library databases

What permissions are found in copyright licensing agreements?

Reproduction

This is the copyright owner’s right and ability to control the new makings of copies.

An example of this right: The permission to convert printed text or images into digital form.

Making Derivatives

This is the copyright holder’s right and ability to control how their creative work is made into new adaptive forms.

An example of this right: The permission to make a transcription from an interview sound recording or transforming a creative work through an editing process.

Copy Distribution

This is the ability to control how a creative work is shared through the transfer to others.

An example of this right: Uploading a copyrighted feature film to YouTube or sharing a copyrighted digital image on Instagam.

Public Performance

This is the copyright owner’s ability to control how their copyrighted work is publicly performed. Public is determined by 1) a place open to the general public; 2) a place where there is a substancial amount of people outside a family or social circle; 3) transmitted in multiple locations. This right does not relate to sound recordings.

An example of this right: Streaming a movie from Netflick at a public event.

Public Display

This is the copyright owner’s right and ability to control the public display of works like photographs, paintings, literary works, and designs. This is similar to public performance rights, but doesn’t apply to performances. It only applies to display.

An example of this right: Adding a full-length poem to a publicly available website.

Frequently Asked Questions About Understanding Copyright

Do I own my copyright?

Copyrights are generally owned by the people who create the works of expression, with some important exceptions:

- If a work is created by an employee in the course of his or her employment, the employer owns the copyright.

- If the work is created by an independent contractor and the independent contractor signs a written agreement stating that the work shall be “made for hire,” the commissioning person or organization owns the copyright only if the work is (1) a part of a larger literary work, such as an article in a magazine or a poem or story in an anthology; (2) part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, such as a screenplay; (3) a translation; (4) a supplementary work such as an afterword, an introduction, chart, editorial note, bibliography, appendix or index; (5) a compilation; (6) an instructional text; (7) a test or answer material for a test; or (8) an atlas. Works that don’t fall within one of these eight categories constitute works made for hire only if created by an employee within the scope of his or her employment.

- If the creator has sold the entire copyright, the purchasing business or person becomes the copyright owner.

As a UO researcher, am I required to follow United States copyright law?

Yes.

Who at the UO can advise me on copyright?

If you need consultation support regarding creator or author rights then you can reach out to the UO Libraries. The UO Libraries have a number of library faculty who specialize in copyright. To reach a librarian connect with them through the DREAM Lab’s consultation services.

What is Fair Use?

Fair Use (Section 107) is a provision written into U.S. Copyright Law that strives to promote the creation of new culture by balancing the public interest in discovery and production of new works, against the rights of the creator of that work. It allows the use of copyrighted works “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research” without the permission of the copyright owner. A Fair Use evaluation is conducted by the user of the work and is based on examining four factors and taking into consideration supporting common law and best practices. It is recommended that Fair Use evaluations be documented and retained by the user of the work.

Fair Use in Seven Words by the University of Virginia Libraries.

The policy behind copyright law is not simply to protect the rights of those who produce content, but to “promote the progress of science and useful arts.” U.S. Const. Art. I, § 8, cl. 8. Because allowing authors to enforce their copyrights in all cases would actually hamper this end, first the courts and then Congress have adopted the fair use doctrine in order to permit uses of copyrighted materials considered beneficial to society, many of which are also entitled to First Amendment protection. Fair use will not permit you to merely copy another’s work and profit from it, but when your use contributes to society by continuing the public discourse or creating a new work in the process, fair use may protect you.

Section 107 of the Copyright Act defines fair use as follows:

[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include —

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

- and the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Unfortunately, there is no clear formula that you can use to determine the boundaries of fair use. Instead, a court will weigh these four factors holistically in order to determine whether the use in question is a fair use. In order for you to assess whether your use of another’s copyrighted work will be permitted, you will need an understanding of why fair use applies, and how courts interpret each part of the test.

Making a Fair Use Judgement Call

Making a fair use judgement is more of an art than a science. It’s a balancing act performed case by case. All judgement calls must consider the 4 Factors of Fair Use.

It is important to note the following practices that could be used to help make fair use judgements:

- Best practice is to always kind the original creator and ask if you can use their work

- Because you work or go to school at an academic institution does not mean you can use any creative works in any way you like regardless if it is for educational or non-commercial purposes

- There are myths around how much of a creative work you are allowed to use. For example: If you are using only a short duration or clip of a film, video music, and sound recording, this does not mean you are protected by fair use

- It is recommended to document your fair use judgements and keep track of research materials copyright information

- Linking or embedding (with attribution) YouTube videos or other videos on content streaming platforms could give you a stronger fair use argument

- If you are reusing research materials that will not be publicly shared and access is controlled then this could benefit your fair use argument

The 4 Factors of Fair Use

What are they and how are they defined?

Purpose and Character of Use

This is the copyright owner’s right and ability to control the new makings of copies.

An example of this right: The permission to convert printed text or images into digital form.

Amount Used

This is the copyright holder’s right and ability to control how their creative work is made into new adaptive forms.

An example of this right: The permission to make a transcription from an interview sound recording or transforming a creative work through an editing process.

Nature of the Copyrighted Work

This is the copyright holder’s right and ability to control how their creative work is made into new adaptive forms.

An example of this right: The permission to make a transcription from an interview sound recording or transforming a creative work through an editing process.

Market Impact

This is the ability to control how a creative work is shared through the transfer to others.

An example of this right: Uploading a copyrighted feature film to YouTube or sharing a copyrighted digital image on Instagam.

Fair Use Case Law: Use it to help you make judgements

The case law listed below are examples of legal cases where fair use was challenged. Reviewing case law ca be helpful when learning how the United States legal system has made judgements about fair use. They can aid in your fair use arguments.

Case Law Examples: Yes, Fair Use

- The makers of a movie biography of Muhammad Ali used 41 seconds from a boxing match film in their biography. Important factors: A small portion of film was taken and the purpose was informational. (Monster Communications, Inc. v. Turner Broadcasting Sys. Inc., 935 F.Supp. 490 (S.D. N.Y., 1996).)

- It was a fair use, not an infringement, to reproduce Grateful Dead concert posters within a book. Important factors: The Second Circuit focused on the fact that the posters were reduced to thumbnail size and reproduced within the context of a timeline. (Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd., 448 F.3d 605 (2d Cir. 2006).)

- An author created a parody of the surfer-thriller Point Break. The court found the work to be sufficiently transformative to justify fair use of the underlying movie materials. At issue in this case was the more novel question of whether the resulting parody could itself be protected under copyright. Important factors: The Second Circuit held that if the author of the unauthorized work provides sufficient original material and is otherwise qualified under fair use rules, the resulting work will be protected under copyright. Keeling v. Hars, No. 13-694 (2d Cir. 2015).

Case Law Examples: Not Fair Use

- A television news program copied one minute and 15 seconds from a 72-minute Charlie Chaplin film and used it in a news report about Chaplin’s death. Important factors: The court felt that the portions taken were substantial and part of the “heart” of the film. (Roy Export Co. Estab. of Vaduz v. Columbia Broadcasting Sys., Inc., 672 F.2d 1095, 1100 (2d Cir. 1982).)

- Several individuals without church permission posted entire publications of the Church of Scientology on the Internet. Important factors: Fair use is intended to permit the borrowing of portions of a work, not complete works. (Religious Technology Center v. Lerma, 40 U.S.P.Q.2d 1569 (E.D. Va., 1996).)

- A biographer paraphrased large portions of unpublished letters written by the famed author J.D. Salinger. Although people could read these letters at a university library, Salinger had never authorized their reproduction. In other words, the first time that the general public would see these letters was in their paraphrased form in the biography. Salinger successfully sued to prevent publication. Important factors: The letters were unpublished and were the “backbone” of the biography—so much so that without the letters the resulting biography was unsuccessful. In other words, the letters may have been taken more as a means of capitalizing on the interest in Salinger than in providing a critical study of the author. (Salinger v. Random House, 811 F.2d 90 (2d Cir. 1987).)

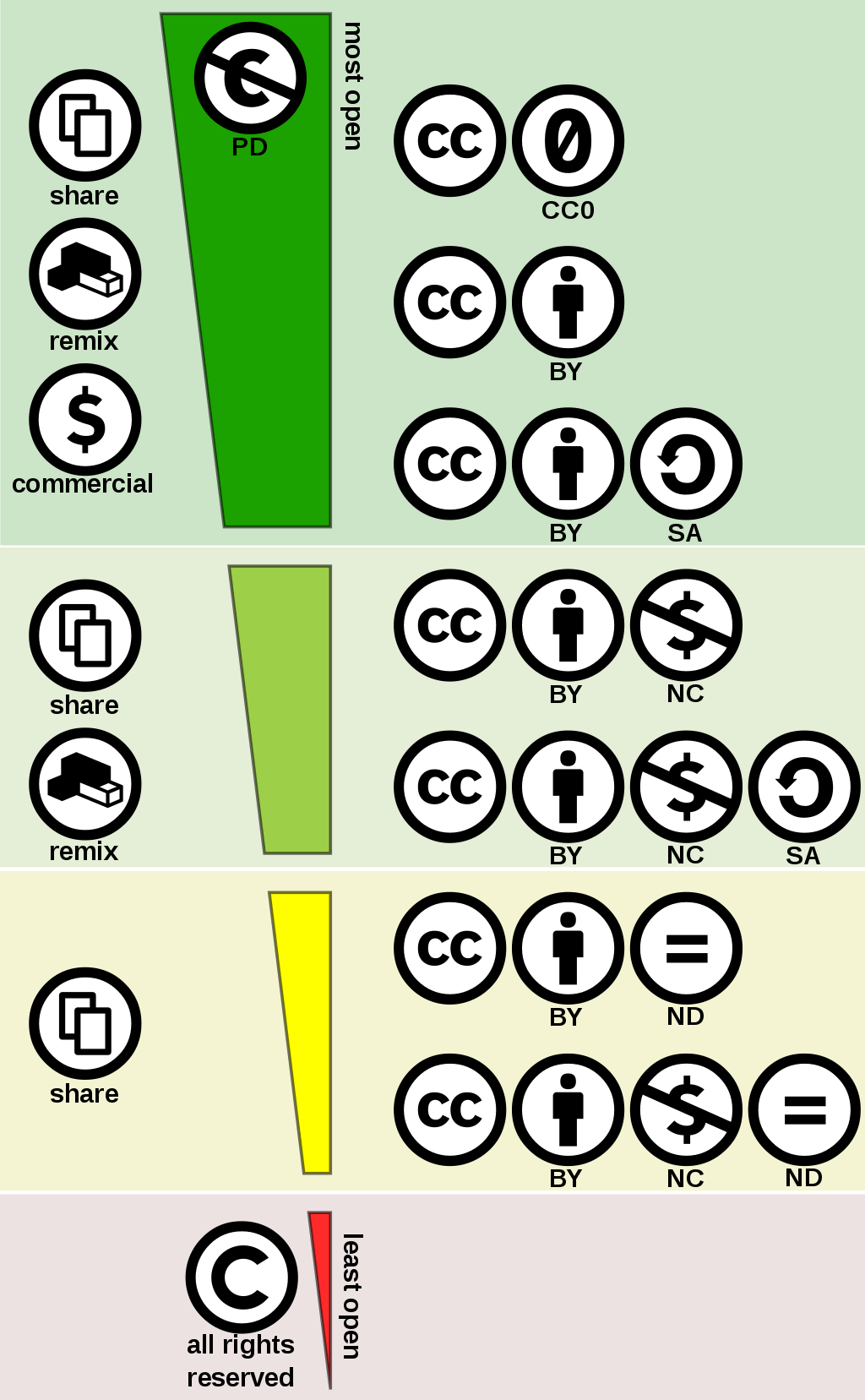

What is Public Domain?

Public domain represents creative works that are not protected by United States intellectual property rights law. The “public” in public domain means a work is owned by the public, not an individual.

Anyone can use creative works if the work is in the public domain.

Every year on January 1st new works become copyright free and in the public domain because copyright has expired.

If a work was created by the United States government then it is automatically public domain.

Works created before 1929 are in the Public Domain

Where to Find Public Domain Content

There are several places on the Internet where you can find public domain content. Usually the organizations and institutions who make public domain content available are libraries, archives, museums, governments, and non-profit organizations. The resources listed below are only a handful of online resources for finding publicly and freely available materials.

Oregon Digital is the University of Oregon Libraries and Oregon State University Libraries & Press’ cultural heritage repository for unique historical materials. There are over 100,000 objects representing Oregon’s history, the universities, and other types of special materials. Not everything in Oregon Digital is in the public domain.

Historic Oregon Newspapers provides access to almost 2,000,000 digitized pages from Oregon’s newspapers dated 1846-2021. Not everything in Historical Oregon Newspapers is in the public domain.

Digital Public Library of America

The Digital Public Library of America is where hundreds of libraries, museums, and archives have rathered all of their historical materials in one single place. There are millions of resources to explore and support your research. Not everything in DPLA is in the public domain.

Library of Congress Digital Collections

Find thousands of public domain resources through the Library of Congress. The scope of these digital collections pertain to historical topics and significance to the United States. You can find sound recordings, photographs, documents, and other resources here.

Project Gutenberg is an online eBook library that contains over 60,000 free books. All content made available through Project Gutenberg are copyright free and in the public domain.

The Getty’s Open Content Images

The Getty makes available over 160,000 digital images of artworks and manuscripts copyright free for anyone to be able to use.

The Internet Archive is a non-profit organization that’s mission is to build the world’s largest digital library for web pages, books and texts, audio recordings, videos, musical performances, images, and software. There are billions of historical materials are available through this resource. Not everything in the Internet Archive is copyright free or in the public domain.

The UO Libraries DREAM Lab can connect you with library and information scientists and other professionals on campus who can assist you with you copyright needs. You can get help with the following copyright topics:

- Identify where to find copyright free and openly licenses resources

- Use copyright evaluation tools

- Give non-legal advisement with making fair use determinations

- Select different types of licenses like Creative Commons and Traditional Knowledge Label

- Figure out how best to connect you with more support at UO through the Office of the Vice President for Research & Innovation

The DREAM Lab cannot do your copyright research for you unless there is a formal partnership and collaboration agreement.

The UO Libraries DREAM Lab can connect you with library and information scientists and other professionals on campus who can assist you with you copyright needs. You can get help with the following copyright topics:

- Identify where to find copyright free and openly licensed content

- Use copyright and fair use evaluation tools

- Give non-legal advice to help determine copyright and make fair use judgements

- Selecting an open license for your research

- Figure out how best to connect you with more research support at the UO

The DREAM Lab cannot do your copyright research for you unless there is a formal partnership and collaboration agreement.

Copyright Resource Guide Authors & Contributors

Kate Thornhill, Digital Scholarship Librarian, author

Franny Gaede, Director of Digital Scholarship Services, contributor

Office the Vice President for Research Innovative Partnership Services, contributor

University of Oregon Libraries Copyright Taskforce 2019-2022, contributor

This guide is licensed with a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Share-Alike International 4.0 License