When the American Association for the Advancement of Science called for more global science engagement at their annual meeting in February, UO Chemistry and Biochemistry alum Edward Sambriski was already on it.

Now on his sixth year as an associate professor of chemistry at Delaware Valley University, Edward couples his teaching responsibilities with regular, month-long trips to Mexico to work on research projects with colleagues at the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico City and the National Autonomous University of Mexico campus in Juriquilla, Querétaro. For Edward, the U.S.-Mexican connection appears to come naturally.

Growing up in Santa Clara, California, of Mexican descent on his mother’s side, Edward is fluent in both English and Spanish. He attended school in Santa Clara through the sixth grade, and then moved to Mexico for the remainder of his middle and high school years, while his mother was teaching there. Edward returned to Santa Clara to begin his college studies, first at Mission Community College and then at San José State University, graduating in 2001 with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and minors in math and physics.

Edward then chose to pursue an advanced degree in chemistry at the University of Oregon, attracted by the variety of research and the interdisciplinary nature of many of the projects. He entered the PhD program in the fall of 2001 and joined the Marina Guenza laboratory the following year. He credits Professor Guenza’s accessibility and mentorship with helping him to develop a solid set of scientific and communication skills that have served him well as his career has progressed.

As a graduate student, Edward earned several honors, including a three-year Graduate Fellowship award from the National Science Foundation. In 2005, he traveled to Lindau, Germany, as one of a select group of students that were chosen to participate in the 55th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting. This notable interdisciplinary event gave Edward the opportunity to meet other young scientists from around the world, and take part in lectures and panel discussions presented by 44 Nobel Laureates. Edward completed his doctoral degree in 2006. His thesis project involved developing analytical coarse-grain models of polymeric liquids to address their structural and dynamic properties.

After graduation, Edward accepted a two-year post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in materials science and engineering. There, he developed a coarse-grain model for DNA, a joint project between the Department of Chemical Engineering, with Dr. Juan J. de Pablo, and the Laboratory of Genetics with Dr. David Schwartz. It was during his post-doctoral tenure at UW-Madison that he met the fellow scientists with whom he would develop his formalized research collaborations in Mexico. The interdisciplinary nature of chemistry is one of the things that Edward likes best about the field.

“The former paradigm of keeping tight borders around traditional areas of knowledge is long gone,” he explains. “It no longer makes sense to “speak chemistry” or “speak physics”. Throughout my career, I have been fortunate to collaborate with specialists in different areas, including physics, engineering, biotechnology, materials science, and mathematics.”

After completing his post-doc, Edward chose to accept a tenure-track position at Delaware Valley University, a small private institution in Pennsylvania – a decision that allowed him to follow a passion for teaching while adding to his distinguished publications list. He finds that the combination of research and teaching brings a sense of freedom and variety to his endeavors, keeping him on his toes.

When teaching at DVU, Edward seeks to challenge his students in their way of thinking about chemistry, both conceptually and practically. He will intentionally build “troubleshooting” into an experiment because it is there, he says, that students often learn important lessons about science. Whether his students are addressing an equipment-related situation in the laboratory or deciphering why an experiment has given them unintended results, watching their creativity unfold as they think outside the box and go beyond their comfort zone is a source of motivation for his instructional work.

During the university’s winter and summer breaks, Edward travels south of the border to work on research with his colleagues in Mexico and to keep up an active publication record. Over the last few years, their projects have centered on the structural and dynamic properties of liquid crystals (LCs) at the nanoscale, with a focus on determining how long a given LC arrangement is stable. Understanding LC stability can provide a means for fine-tuning LC-based applications, which have a wide variety of uses – from medical uses, to solar energy, to food safety, to electronic and optical devices.

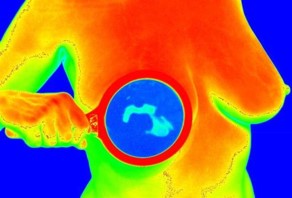

One of the LCs that Edward and his colleagues study are thermotropic (temperature-responsive), which can detect slight changes in temperature. Applications utilizing this type of LCs can have an impact on health care and disease detection in remote regions of the world. For example, in places where routine mammography is not readily available, thermotropic LC films can be used to detect breast cancer. Because cancer cells tend to be warmer than normal cells, LC films can detect temperature differences in breast tissue and produce a visual response.

“The problems of today are multifaceted and require the contributions of individuals from many fields,” Edward says. “Research projects are now inherently multidisciplinary. The drive to work closely with others to learn as well as to achieve a common goal is both inspiring and rewarding: it is no longer “my story”, but “our story” of a research problem.”

As his interdisciplinary collaborations continue to grow, Edward hopes to establish an international exchange for researchers between his institution and the universities he is associated with in Mexico. And his efforts will continue to foster just the sort of partnerships and global science engagement we’ll need to take on the challenges that face our world – today and in the years to come.

– by Leah O’Brien

UO Chemistry and Biochemistry