Lauretta Bender (courtesy of Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections, Papers of Dr. Lauretta Bender)

Lauretta Bender repeated first grade three times in her home town of Butte, Montana during the first decade of the twentieth century. Teachers considered her mentally defective and she worried that she would never learn. This turned out not to be true, but Bender’s fear and frustration as a young girl may have influenced her decision to become a child psychiatrist. It certainly shaped her belief that developmental and learning problems were rooted in neurological differences, or what we now call neurodiversity. “We all have a bit of cellular loss, brain damage, deviations here and there,” she said in 1960. “This is something that is hard for people to accept.”

Bender was one of the first American physicians to treat and study children with schizophrenia and severe emotional disturbance, terms that were common at the time. She encountered hundreds of severely effected children, including children with autism, during her long career as a researcher and clinician. She also applied her professional perspective to her own children, two of whom had difficulties with writing and spelling. Bender was convinced they had inherited these traits, which would be eventually be recognized as learning disabilities, from her.

Lauretta Bender with her three children, Long Beach, NY. She was certain that two of them had inherited her learning disabilities. (courtesy of Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections, Papers of Dr. Lauretta Bender)

Bender’s biological orientation as a psychiatrist made her a maverick during much of her career, especially after 1945, when psychoanalytic perspectives dominated psychiatry in the United States and psychogenesis was the dominant theory about autism. During her lifetime, Bender was well known and widely respected, above all for developing a neuropsychiatric exam, the Bender-Gestalt Visual Motor Test. First published in 1938 by the American Orthopsychiatric Association, the Bender-Gestalt test was one of the most frequently used tests for assessing brain damage and developmental disorders.

Bender’s important role in the history of autism has largely been forgotten, at least in comparison to Leo Kanner, whose 1943 article on autism is invariably credited with making autism visible as a clinical syndrome. During her lifetime, however, Bender was considered a national and international expert, and Leo Kanner and other leading child psychiatrists regularly sought her out for advice. In 1942, Bender called childhood schizophrenia, as autism was then often called, “a definite syndrome,” a “pathology at every level and in every field of integration within the functioning of the central nervous system, be this vegetative, motor, perceptive, intellectual, emotional, or social.” Before he published his famous article about autism, Leo Kanner consulted Bender about eight cases of early life regression that she had described at a meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Several of Kanner’s and Bender’s cases overlapped.

Lauretta Bender, during her training in Amsterdam in 1927-28 (courtesy of Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections, Papers of Dr. Lauretta Bender)

Bender attended the University of Chicago as an undergraduate, where she also earned an MA in Pathology in 1923. She completed her MD at the University of Iowa in 1926. After a year of laboratory training in neuroanatomy in Amsterdam, she worked at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital and then in the Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins University. At Johns Hopkins in 1929-1930, Bender conducted a detailed case study of 90 women with schizophrenia, all residents of Springfield State Hospital in Sykesville, Maryland. Many of the women were mute. Encountering patients with whom she had to communicate non-verbally sensitized Bender to visual cues, such as body language and posture. These would serve her well in her work with children.

During her year at Phipps, Bender worked with Adolf Meyer, the most prominent psychiatrist in the country, and also got to know Leo Kanner. At a clinic staff conference, Bender met Paul Schilder, an émigré psychoanalyst and contemporary of Sigmund Freud’s. Schilder was married at the time, but Bender followed him to Bellevue Hospital in New York in 1930. After his divorce in 1936, they married. Schilder died just four years later, in a tragic car accident, shortly after Bender delivered their third child.

Bender’s education had not prepared her to work with children, but no real training in child psychiatry existed in 1934, when Bender became the first director of the children’s inpatient ward at Bellevue Hospital. She remained at Bellevue until 1956, when she was appointed Director of Research in the new children’s unit at Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens. She retired from Creedmoor in 1964 and remarried in 1965. Her second husband, historian Henry Benford Parkes, died in 1973.

Bender’s research on childhood schizophrenia and psychosis was important. Her exploration of the genetic and neurological origins of autism was unusual at the time. Bender believed that the seriously affected children she saw at Bellevue all had one thing in common: “maturational lags.” These lags prevented children from growing by inhibiting normal patterns of language, perception, motor coordination, and interpersonal relationships.

The severe behavioral symptoms presented by autistic children resulted from these lags. From the 1930s through the 1960s, Bender saw many children who would now be placed on the autism spectrum as well as others who would be diagnosed with ADHD, fetal alcohol syndrome, and learning disabilities. They showed signs of abrupt developmental regression or exhibited behaviors like whirling, head-banging, mutism, echolalia, and obsessions with inanimate objects. They had sleeping, feeding, and respiratory problems. All of them departed from developmental norms standardized during the 1920s, paralleling the rise of standardized height and weight tables in pediatrics.

When Bender used the term autism, she treated it as part of a larger spectrum of childhood schizophrenia. Autism rarely occurred in pure form, but typically combined with other developmental and psychiatric symptoms, including mental retardation, hyperactivity, and aggression. She had no patience for the mother-blame that was central to psychogenesis. Instead of scrutinizing parents for signs of emotional sabotage, she urged sympathy for parents who faced the challenge of caring for unresponsive, unpredictable offspring. By the time children arrived on her ward, Bender believed they suffered from “a psychoneurobiologic entity determined by heredity,” caused by an “organic insult with a maturational lag in all areas of functioning.” Such comprehensive failure of normal development qualified as “encephalopathy.” If Bender located autism anywhere, it was in the brain.

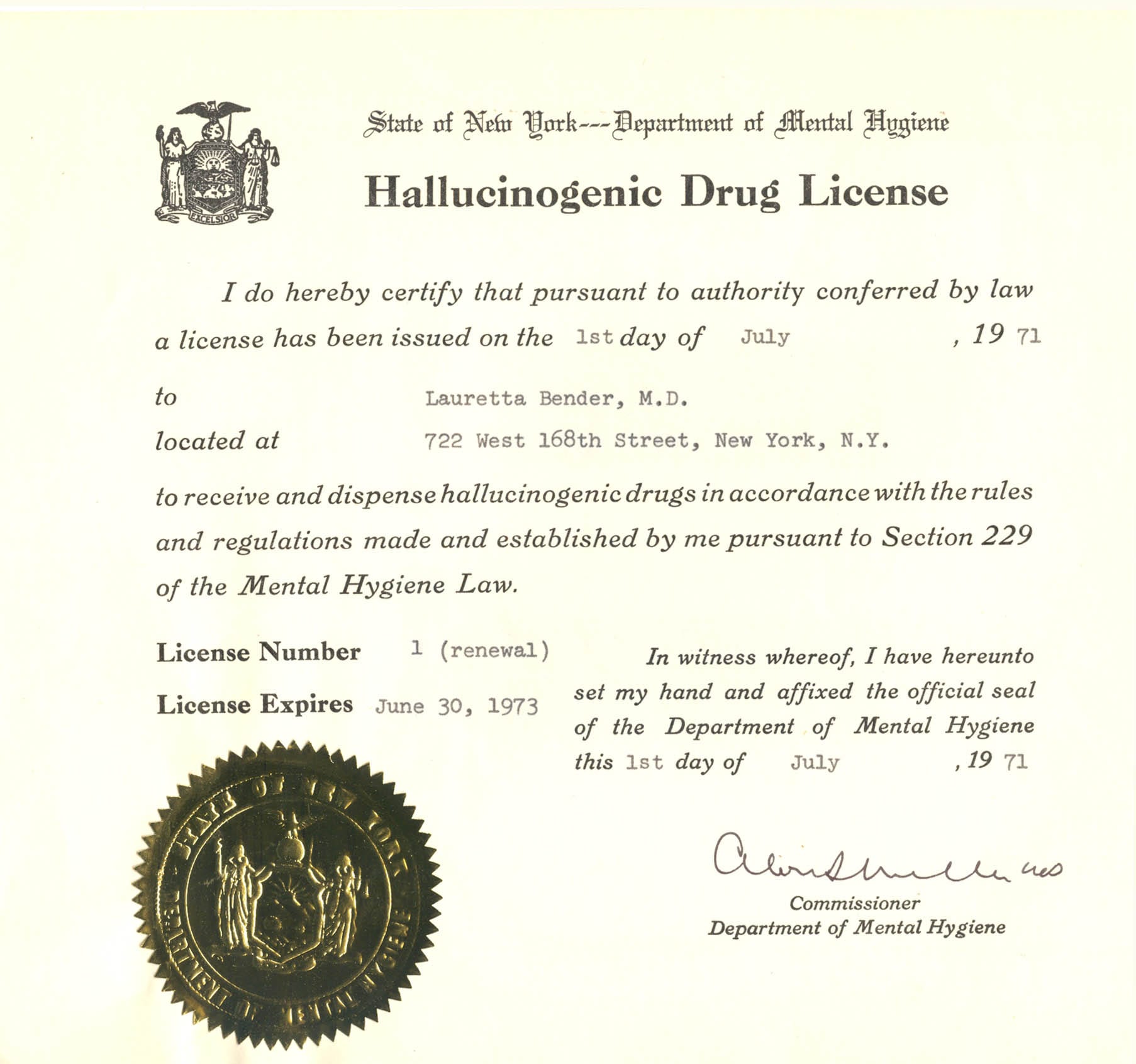

Her emphasis on brain damage pointed toward neurological and psychopharmacological interventions as productive avenues of treatment and research. Bender administered ECT, major tranquilizers like thorazine, hallucinogens like LSD, and other psychoactive drugs to children as young as three years of age. By the mid-1950s, Bender estimated that more than 500 children at Bellevue had received ECT, typically daily for a period of 20 days. She always maintained that shock was safe and effective in eliciting more appropriate behavior from children, and her follow-up studies of children treated with shock never caused her to reconsider this practice. As for drugs, Bender hoped that LSD and a derivative, UML (brand name: Sansert) might benefit autistic children by providing psychedelic experiences that would mobilize perceptual growth and reduce developmental lags. She began testing that theory on children at Creedmoor in 1961, where she administered these drugs daily to almost 100 children. Many of them took these drugs for months at a time and several for years. Bender considered the outcomes positive.

Lauretta Bender at Creedmoor State Hospital Children’s Unit for the 1961 football team award. During her years at Creedmoor, Bender’s research included administering shock and psychoactive drugs, including LSD, to autistic children. Dr. Harry LaBurt, Director of Creedmoor, is on the right. (courtesy of Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections, Papers of Dr. Lauretta Bender)

Lauretta Bender’s license to administer hallucinogenic drugs (courtesy of Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections, Papers of Dr. Lauretta Bender)

Most of Bender’s career unfolded during an era when clinical experimentation in institutions (orphanages, state hospitals, and prisons) was routine and before stricter regulations of biomedical research and requirements for informed consent were put into place by the federal government. From today’s vantage point, her use of shock and drugs appears shocking, in spite of the recent trend toward using psychoactive substances to treat serious cases of depression and addiction. Research ethics and protocols have changed significantly since the 1960s, and Bender’s research on children could not be justified today.

Her basic perspective on autism and her views about what autistic children need most, however, have endured. She called autism “one of the most challenging problems in psychiatry…short of actual suicide” and demanded “energetic treatment” for children otherwise destined to become “lost souls.” She also took a very forceful position on the rights of developmentally disabled children. After Brown v. Board of Education, which made racial segregation in American schools unconstitutional, she called for “a new bill of rights which will say that no child will be discriminated against because of a medical or psychiatric diagnosis.” Bender argued for equal opportunities not only in health care and social services but in education as well. She may be little known today, but Loretta Bender was a key figure in autism history.