Hans Asperger is famous for giving his name to “Asperger syndrome,” or high-functioning autism. Asperger described this syndrome in 1944, one year after Leo Kanner published his iconic article on autism. Asperger, an Austrian physician, presented case studies, just as Kanner had, about “a particularly interesting and highly recognisable type of child.” In 1950, Asperger visited the United States to meet other pioneers in child psychiatry and autism research. He wrote in German, however, so his influence outside of continental Europe was limited to specialized professional circles during his lifetime. He did not live to see the global impact of his ideas or his name.

Asperger’s work was brought to wider attention in the English-speaking world by British autism researcher Lorna Wing in the early 1980s, who wrote about Asperger’s concept of “autistic psychopathy.” His 1944 article was translated into English in 1991 by Uta Frith, a German-born autism researcher who worked in England. Asperger syndrome was included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) for the first time in 1993 and in the DSM for the first time in 1994.

After that, Aspeger was often portrayed as a champion of neurodiversity far ahead of his time. Recent scholarship, however, has revealed Asperger’s ties to the genocidal medicine of the German Third Reich. Asperger did not belong to the Nazi Party, but he referred disabled children to the Am Spiegelgrund clinic in Vienna’s Am Steinhof psychiatric hospital, where almost 800 children were murdered between 1940 and 1945 as part of the regime’s euthanasia program. This discovery has provoked debate about the degree of Asperger’s complicity and questions about why his involvement remained secret for so long.

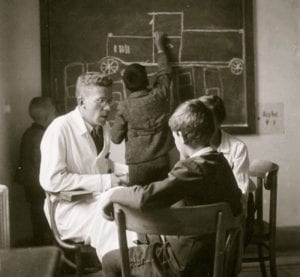

Born and educated in Vienna, Asperger spent virtually his entire career there. He held a chair in pediatrics at the University of Vienna and also taught at the University of Innsbruck. Toward the end of World War II, during the Nazi occupation, he ran a clinic for children with autism at the University Pediatric Clinic; it doubled as a residential school. In this setting, Asperger collaborated with Sister Viktorine Zak, a talented nurse. Zak may have been among the first to devise customized therapies—incorporating music, movement, and speech—for children with autism. (Interestingly, there is some evidence that a Dutch nun, Ida Frye, known as Sister Gaudia, worked with autistic children almost a decade earlier at the Catholic University in Nijmegen.) Zak was killed and the clinic destroyed when the clinic building was bombed in 1944.

Asperger’s interest in the developmental characteristics he documented was autobiographical, and he scattered tidbits about his own experience throughout his writing. As a child, Asperger was solitary, found it challenging to make friends, and was so interested in the poems of Franz Grillparzer that he recited them obsessively, alienating many of the children and adults around him. By the time he was nine, he had read all of Grillparzer’s plays. Asperger referred to himself in the third-person.

In spite of these eccentricities, Asperger achieved educational and professional success as an adult. He married and had four children. But his own childhood surely helped him empathize with the children he wrote about in 1944. His article described four boys in detail but noted that he had seen more than 200 cases of autistic psychopathy over a ten-year period. It was possible “to consider such individuals both as child prodigies and as imbeciles with ample justification,” he commented at the outset. Two of the boys were exceptionally gifted at math and two had unusual verbal facility, but all of them found simple daily routines, easily comprehended by most young children, mysterious. That they were eventually able to master any of them indicated their “delightful” originality, Asperger wrote, since they could not rely on conventional methods of social learning that were second nature to most children. The implications for education were clear. Children who had to learn from their own experiences rather than by imitating others explained why some very smart students performed poorly in school.

Indeed, “extraordinary levels of performance in certain areas” were characteristic even as “the special abilities and disabilities of autistic people are interwoven.” Unlike Leo Kanner, Asperger believed that autism could be present either in highly intelligent children or in children with mental retardation. Social disabilities could be so profound in some individuals with autism that they made independence literally impossible, regardless of intellectual ability. Others, however, could hope for independent lives. It was precisely their autistic characteristics that would help these fortunate individuals achieve educational and occupational success. Autism spared them from ordinary distractions and allowed them to focus their efforts single-mindedly on artistic, scientific, or other pursuits.

Autistic psychopathy was a permanent condition, Asperger believed, and probably a genetic one. Although he lived in the same city that made Sigmund Freud famous, Asperger had little use for psychoanalysis. Instead of delving into dreams or memories, he emphasized children’s inability to maintain direct eye contact or understand others’ facial expressions, their linguistic abnormalities, and their variety of strange fixations. He noticed that they were often hypersensitive to taste, touch, and sound. He also noticed that these children were frequently born to parents who displayed milder versions of the same behaviors. All of these pointed toward hereditary factors.

So too did autism’s gender gap. Many more boys have always been categorized as autistic and several of the syndrome’s telltale symptoms resemble caricatures of conventional masculinity. Decades before neuroscientists began thinking about gendered brains, Asperger wrote that “the autistic personality is an extreme variant of male intelligence.” Logical and abstract thinking came easily to the boys he worked with, where it lived uncomfortably alongside great voids of social competence and emotional intelligence. Asperger appreciated that autism might be a highly exaggerated expression of typical gendered behavior.

Asperger’s own experience, combined with the fact that he encountered autism in children who functioned exceptionally well in specific areas, such as math or literature, provided him with an insight we continue to wrestle with seventy-five years later. If autism shapes behavior in ways that are different in degree rather than kind, isn’t it also likely that autism is not at all rare, that all persons exist on an autism spectrum that spans humanity?