From January 21 to April 8th, the UO art faculty members will be showing their work in The Long Now, an exhibition at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art from January 20 to April 8 in Eugene. Selected works by six art faculty members will be shown at the White Box in Portland from January 24 to March 24. To highlight the artists behind the art, I’m having conversations with several of the faculty in the show to hear more about their practice.

This conversation is with Surabhi Ghosh. Whether she is drawing, painting, printing, stitching, or bookmaking, Ghosh is always invested in the idiosyncrasies of visual language. Her current research centers on the meaning of pattern and decoration within spiritual, political, and domestic narratives. Focusing on ubiquitous motifs like the circle and the dot, she creates abstract compositions that blur the lines between painting, sculpture, and textile design.

Ghosh is also co-director of an international artists’ collective and annual publication project known as ‘Bailliwik,’ which she cofounded in 2004. Her work and collaborative projects have been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues including Western Gallery at Western Washington University (Bellingham, WA), NEXT Art Fair, MDW Art Fair, and Lillstreet Art Center (Chicago, IL). Her books are included in several collections worldwide. She has an upcoming exhibition at SideCar Gallery in Hammond, Indiana.

Dave Amos, A&AA writer: You’re the fibers professor, but a lot of your work is not in fibers. Why?

Surabhi Ghosh: My background is in fibers; I have a BFA and an MFA in fibers. I’ve been teaching in that field for the last six years at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. About three years ago I switched my focus from working with fabric and textiles.

I’m particularly interested in repeat pattern design. I started doing small-scale drawings and paintings, approaching them as sketches or experiments about color and pattern. I realized I liked doing those and that I wanted to get bigger, focus, and improve on my technique. Since about 2008, I’ve mainly worked in painting, so now I’m as much a painter as a fiber artist. I don’t mean to imply that I’m never going to go back to fibers. It’s in my bones at this point.

And I paint using a somewhat non-traditional process: I use paint as liquid color. All of my recent work is made up of accumulations of dots, and each dot is made by putting a little drop of paint down. I use a really small brush, load it up with paint, and make a little drop instead of a stroke.

DA: Why use this technique? Is it fibers related?

SG: Yes, the very small, repetitive mark that I’m drawing on is related to various fiber techniques. I connect it to embroidered stitches as well as quilt-making, where patterns are pieced together by combining many different pieces of fabric. I also think about crochet structures and woven structures when I make my work. I create these swirling micro patterns within the larger form, and I relate that process formally to crochet, which is really important to my experience with fibers.

DA: That makes sense. Are the designs themselves inspired by fibers?

SG: They grew out of my interest in decorative border patterns. In Indian textiles decorative borders are very common. Saris always have borders around the edge, and they are often very abstract, very geometric, very decorative. The edges are embellished, and that edge is embellished, and then that edge is embellished–a motif is always edged with another decorative motif.

In my work, I reflect on the way patterns build incrementally. I never have a plan, but I use a roughly geometric system, which, when applied dozens or hundreds of times, creates unpredictable patterns. These patterns emerge out of the simple system of dot placement I use. I’m interested in that process of handmade geometry.

DA: How do you choose the colors in your piece?

SG: My color decisions are intuitive. Because of how the dots are built, each line is building on what came before each. With each subsequent line I make a decision about color. Sometimes I decide I want it to be a gradation, and sometimes I decide I want a contrast.

DA: So you don’t decide exactly what the finished piece will look like ahead of time?

SG: I draw out the basic contours and make that shape into a stencil. I often work in series, so I like to have them as stencils so I can use that exact same shape again but in a different way. If you look at my work chronologically, you can see that I have been simplifying and simplifying, and what I’m doing right now is purely focusing on the circle and the oval.

This piece was a huge change (Orb 1, above). This happened at the beginning of last year. It’s essentially a circle I’m filling in with dots. I’m interested in evoking the similarity between macro and micro views. This piece can suggest a map of continents and bodies of water or an orbital view of a planet of some sort, while it also resembles a view through a microscope of a sample.

DA: You have also used formats and techniques beyond fibers and paint in the past. Do you still?

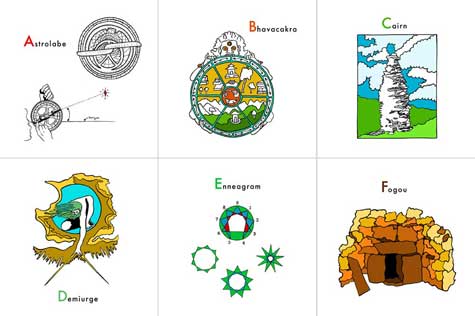

SG: I’m interested in the book form and I always make books; it’s a regular part of my practice. I tend to use them to conduct experiments, create samples, or research ideas. For example, when I started using the circle primarily in my work, I wanted to know more about the circle as a decorative motif. I did this project with my husband, partner, and collaborator called See Ouroboros Run (below), where we researched circular motifs and how they recur in obscure or ancient belief systems, what various meanings circles hold, and if is there a universal meaning behind the circle. Those ideas were housed in a book made to look like a teaching tool, maybe for kids, which established a fictitious belief system from a conglomeration of sources. I’m interested in visual storytelling and comic books are a big influence on my work. I tend to make two or three books a year like this, in small editions.

I’m also coeditor of Bailliwik. It’s an annual anthology that works as an artist cooperative — everyone in it submits work and chips in some money. My partner and I do the layout and have it printed. We encourage special projects and limited edition works to include along with the printed book and once everything is assembled we send copies to the contributors, who then distribute them however they like. All of the work is also published online on our website. It’s a total DIY artist project. We’ve been publishing since 2005 with eight issues so far. At first we put out two a year, but it almost killed us, so now it’s annual.

I love books as a venue for the arts – as an alternative to a gallery or museum. It’s something that people can take home and sit on their couch and look at. Maybe we can reach a different audience than people who go to galleries or museums. It’s more personal, more intimate.