Assistant Professor Philip Speranza’s fall studio “Public Use of Private Space,” was a unique collaboration between the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts and a private owner in Detroit and her architect brother in New York City. The students’ work provided design development for a proposed community food market and its associated exterior space for a variety of uses.

At the time students enrolled in the studio they were not aware they would be traveling to Detroit, Michigan, as part of the course. However, for the students to visit the project’s site and fully grasp how their proposed urban design installations will aid the client’s community food business, it proved invaluable.

“The trip snapped the students out of their comfort zones and allowed them to better know the space at which they were working. Going to a place creates a connection between what you see as the culture seen from a distance, and then actually experiencing the urban space and getting to know the people,” said Speranza.

“It also allowed the students to better understand the project as a system of connections between the city, the community, the site, and the entrepreneur. It’s not an abstract single thing. They must deal with all of these connections to have a successful project. This allowed the students to be part of the process.”

The project site contains a former bank building and an adjoining parking lot. The designs varied but the goal was to connect the private building to the community at the grass roots level by inviting them into the public space, testing Speranza’s research ideas of “bottom up urban design” acknowledging conditions of the site as a system over time.

The class traveled to Detroit as part of the midterm review following weekly teleconference meetings with the client team throughout the term. The trip’s cost was split between the client and Speranza’s UO research funding. In addition to the midterm review and site visit, the students traveled throughout the region and met many residents of this “shrinking” city.

Speranza was amazed at the disparity between blocks surrounding the project’s site. “Within a block or two of the site, the blocks are totally abandoned with empty lots–what we know of Detroit. And then a block or two on the other side there are large gated houses on one-acre lots. It was bizarre,” he said.

Madison Jackson, a second-year master of architecture student, was impressed by the strong sense of community within the neighborhood and throughout the whole city. “Everyone we met was so invested in the city. I believe this is because it’s easier to move out to the suburbs and not deal with the collapse of the city. Therefore, the people who have stayed behind or moved back all care, want to work hard, and do what they love in their city,” she said.

The studio provided Jackson and her peers a unique experience not available in other courses. “The fact that the studio was an actual project with a real client was the biggest difference and the most important part for me. It was useful to experience pitching an idea to a client and getting their feedback. That it is such a big part of an architect’s job and something that can’t easily be taught in school,” said Jackson.

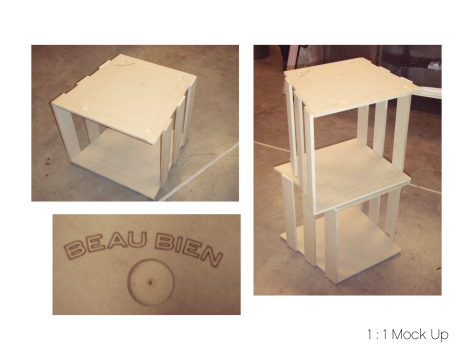

In addition to fostering the students’ designs for the food market, the client also seeks a fully fabricated installation. They selected Jackson’s “Adaptive Market” design as the preferred option for the space. Just like Detroit as a city is learning to adapt and change, Jackson sees her design allowing for the installation to shift as the client, community or seasonal needs change and adapt. “Seasonally the shelves would be converted from seating, to workspace, to shelves, and be further reconfigured throughout the space in the market to best suit the needs of the client and her vendors,” she said.

The client, Jackson, and Speranza will collaborate with the architecture department student group the Digital Media Collaborative (DMC) to fabricate and deploy the “Adaptive Market” design during the upcoming winter and spring terms. Jackson will be part of the group and is looking forward to this opportunity. “Having a studio project deployed is something that does not happen often in school, so I can’t wait to move forward with it,” said Jackson.

The next phase of the project will be the deployment and installation of the group’s design this spring. However, before it makes its way to the project site in Detroit, Speranza has plans to deploy the installation in Eugene. “I’m speaking with local food organizations, property owners, and area farmer markets to deploy the installation,” he said. An independent study of national food desert criteria and neighborhood planning with student Aliza Tuttle, an undergraduate geography student, has been done in parallel to the studio, identifying neighborhood spaces of deployment and installation west of Skinner’s Butte and the Whitaker as places of deployment in the spring.

The studio was just the beginning of the year-long project, but it has provided the students exceptional lessons that didn’t end with its final review. “The studio gave the students the knowledge and experience of what it means to make something, whether that is the software, the fabrication tools, or the physical making of the object in a 1-to-1 scale – not a representation of the idea, but an actual experience of the idea,” said Speranza. “This connects the students to a real experience, both for the individual understanding of art, architecture and design, and also a connection to the community.”

Jackson agrees with her professor and says she found a real connection with Detroit, as did many of her peers. “The studio has inspired me and many of the students to become more involved in Detroit in the future because it is such an amazing city and we all fell in love with it,” she said.

Story by Joe McAndrew

—–

For more information about the “Public Use of Private Space” studio, please visit the studio’s blog here.