While there has been a good amount of speculation about how Shared AV’s (SAV) will push or hinder sprawl, little of it is based on research. This new study (presentation linked) by Wenwen Zhang and Dr. Subhrajit Guhathakurta from Georgia Tech uses a sophisticated analysis of travel datasets from Atlanta coupled with home purchase information from Zillow to predict how fleets of SAV’s might shift where people will choose to live. While the study has some aspects to work out (value of travel time, pricing effects of new mobility on housing), the takeaway is a substantial shift in residential preference.

Author Zhang states that “The transportation system we investigated is Shared Autonomous Vehicle (SAVs) which is a ubiquitous transit system. Our results show that younger households (<40 years old) will move further away from downtown for cheaper housing units and better education resources. Meanwhile, elder households (>40 years old) will move towards the downtown area to avoid long average waiting time. However, all workers will move further away from their working places. The best interpretation of our model results would be workers will have more freedom in terms of residential location choices, i.e. they can live closer to other education facilities and infrastructures that they need to consume, rather than being constrained by the location of their offices.”

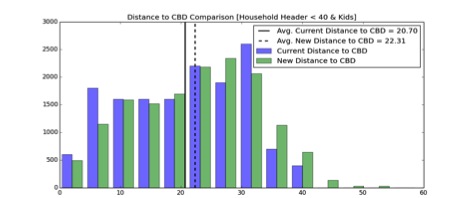

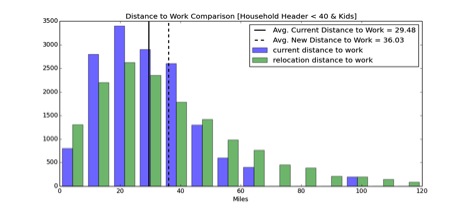

The image below – from the study – sums up how a post AV/ridesource world will have more people choosing to both live and work farther from city centers. (blue is current household distance from CBD or work, green is AV future distance from CBD or work). The charts shown are for people under 40 with kids.

It should be noted that this study focuses on SAV’s where wait times are the key factor pushing some people to live closer in and within higher densities (to avoid wait times). We might rightly assume that privately owned AVs (that eliminate wait times) could push people further out.

This should be a wake-up call to anyone worried about sprawl.

Distance of Household to CBD:

(Avg Current = 20.70 miles, Avg w/ SAV Fleets = 22.31 miles)

Distance of Household to Work:

(Avg Current = 29.48 miles, Avg w/ SAV Fleets = 36.03 miles)

Save

Save

Save

Save