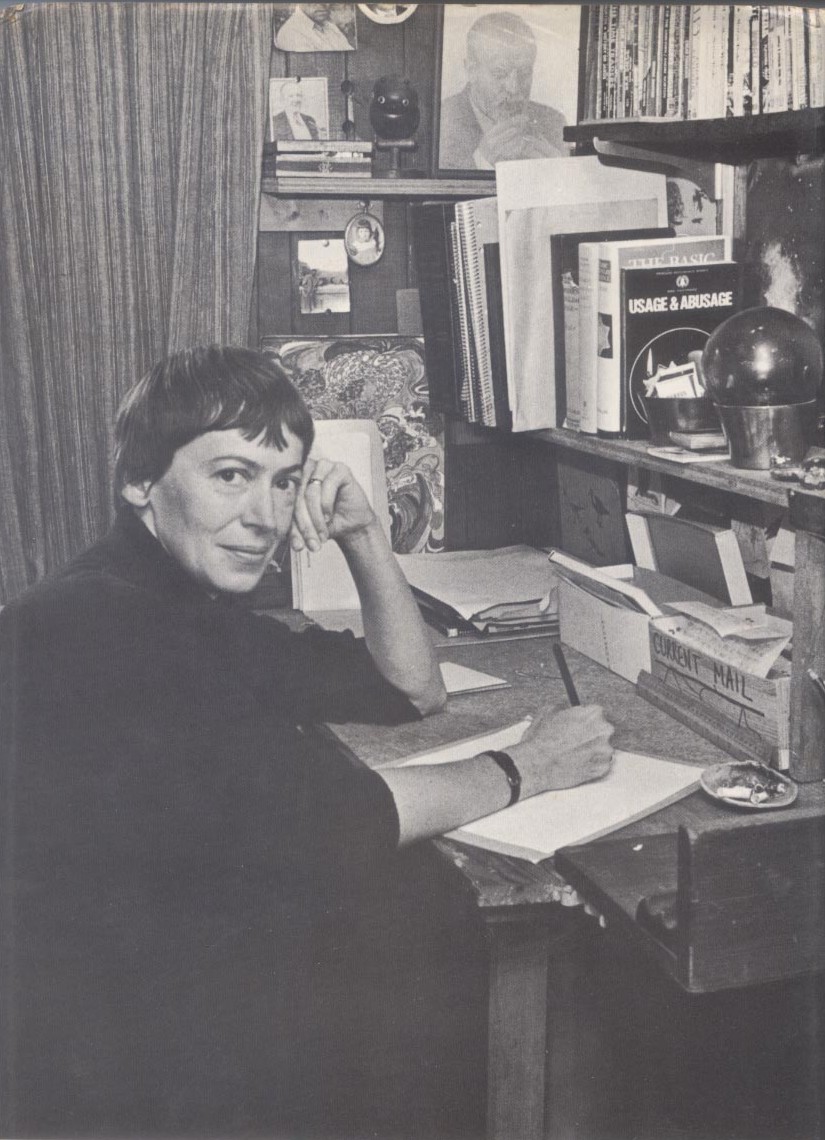

“Something Ineluctably Masculine”: Science Fiction Visionary James Tiptree, Jr.

“It has been suggested that Tiptree is female,” Robert Silverberg wrote in the introduction to a 1975 collection of stories by James Tiptree, Jr. “[It is] a theory that I find absurd, for there is to me something ineluctably masculine about Tiptree’s writing.”

A year later, the award-winning and notoriously private Tiptree was “outed” as Alice B. Sheldon—world traveler, military officer, intelligence analyst, research scientist, and undoubtedly female.

Alice did not set out to become a science fiction writer. An avid reader of Golden Age pulp adventure stories, she saw the genre as an escapist, guilty pleasure. In the 1960s, however, science fiction was changing. A new generation of writers began to take the genre seriously. In its tropes of space exploration and alien encounters, they found uniquely suitable grounds for imagining social change. Alice—who had struggled for years to be a “serious artist,” searching in vain for words to express her dreams of escape, her secret longings, and her dark despair—at last discovered her literary voice.

In 1967, even as Alice studied for psychology exams and wrote up her doctoral research, fast-paced and fantastical stories kept popping into her head. She began to write them down. Since male bylines were more common in science fiction, she thought about creating a penname. One day while grocery shopping, inspiration struck. Seeing a jar of Tiptree brand jam, Alice said, “James Tiptree!” Her husband, Huntington added “Junior!” and they laughed. Alice went home, typed cover letters as “James Tiptree, Jr.,” put the stories in envelopes, and sent them off to leading science fiction magazines. Tiptree sold three stories in six weeks.

As he published more work and his reputation grew, he began to exchange letters with some of the best writers and editors of the day. Concerning his own life, Tiptree—or “Tip,” as his many epistolary friends called him—dropped hints about working with the government, but declined to provide biographical details. His return address of McLean, Virginia had strong associations with government agencies, not least the CIA. Hints of a clandestine professional life turned out to be the perfect red herring. For a long time, it did not occur to anyone that Tiptree’s real secret lay in gender.

*****

Adopting a male persona gave Alice greater freedom than ever before for self-expression. In fiction and written correspondence, writing as “Tiptree” freed her to explore various aspects of her identity, to talk about male domains, and to express love for women. Through science fiction’s metaphors for alienation and otherness, she said things she could not express writing as a woman within the confines of “realistic” literature.

Right from the beginning, Tiptree had original ideas that defied the traditional science fiction vision of rational man and the scientist hero. In “Your Haploid Heart” (1969), an anthropologist discovers terrible truths about a planet inhabited by what seems to be two humanoid species, but is revealed to be a single race with split reproductive phases—one phase sexual and the other genderless. The story’s male protagonist and action-packed plot mask its subversive interrogation of “natural” sex roles that, Tiptree argued to the editor John W. Campbell, Jr., “destroy human identity, and reduce it to a physical breeding-phase—a ‘baby factory’ so to speak.”

Professional recognition led Alice to rethink Tiptree’s writing style. Readers were taking his stories seriously, so maybe she should as well. Alice moved away from action-adventure plots to test, as Tiptree told Philip K. Dick, “how much human reality the sci-fi fabric will

bear.”

While narrative speed and intensity remained hallmarks of Tiptree’s writing, new stories also featured unusual perspectives and an emotional tone. A major theme is sex coupled to death—the longing for union with another, and the real fear of being destroyed by that union. In the Nebula Award-winning story “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” (1973), a giant, sentient bug struggles against reproductive drives toward a higher consciousness. In “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side” (1972), humans have discovered alien life and their instinctive response is sexual. The protagonist warns readers, “Man is exogamous—all our history is one long drive to find and impregnate the stranger. Or get impregnated by him; it works for women too.”

Tiptree’s most haunting work often extrapolates the extreme edges of social norms, such as the Hugo Award-winning story “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (1973). The novella describes a horrifically deformed girl who is wired into a network in order to animate the luscious but physically numb artificial body of a movie star. In this allegory about performing the feminine–described as the first cyberpunk story–the beautiful outer shell houses the unacceptable true self.

*****

Notoriety had its rewards and its costs. Pressures increased for Tiptree to produce a novel, to receive awards in person, and to speak out as a male feminist about sexism in science fiction. Alice experimented with a second writing persona, Tiptree’s female protégé Raccoona Sheldon, and in 1977 won a third Nebula with “The Screwfly Solution,” published under that penname.

By then, however, Alice Sheldon’s double-façade had been blown open.

Comments by Tatiana Bryant