Note: This is a fairly expansive piece but it became a little long. That said, worth the time.

Introduction

In the wake of the less-than-spectacular though I think underrated November employment report research shops are rushing to tell clients that the Fed will most certainly shift the pattern of asset purchases out toward the longer end of the yield curve. I find this to be a curious position given that Fed speakers have literally said both implicitly and explicitly not to expect changes to the asset purchase program at this next Fed meeting. I have written on this once already but the topic deserves another examination given what will be increased attention on the Fed’s upcoming meeting. From my perch, there appears to be a communication error in the making. That said, I am going to lay out (again) the case for additional Fed easing and the alternative, and I think more likely, scenario.

Recent Fed Communications

Here are what I see as the prominent elements of the Fed’s recent communications:

First, the Fed wants to emphasize they are not considering raising interest rates. This is fairly straightforward. The Fed does not want to repeat the mistakes of the last cycle and engender expectations that its fundamental focus is policy normalization.

Second, the Fed’s new strategy suggests that public comments from FOMC participants will have a downward forecast bias, particularly for the near term. In one of my classes, we do an exercise in which the forecaster has an asymmetric loss function such that errors on one side of the forecast are more costly than errors on the other side. As a consequence, the forecaster should bias their forecast to minimize the odds of a forecast error on the “wrong” side of the distribution. The Fed has explicitly adopted an asymmetric loss function in its policy framework:

Owing in part to the proximity of interest rates to the effective lower bound, the Committee judges that downward risks to employment and inflation have increased.

The rational thing to do when you have such a loss function is to emphasize the downside risk. In other words, when making policy considerations, the Fed is biasing their forecasts down to mitigate the risk associated with being close to the effective lower bound. This supports an excessively pessimistic public position and one in which the Fed will say more policy support is likely needed even if an unbiased forecast says no such support is needed. This will encourage market participants to look for reasons to expect easing even if no such reasons exist.

Third, the Fed is “woke.” The Fed has long ignored the micro-consequences of its actions, choosing instead to focus on the macro story. In my opinion, this focus has in the past led the Fed to embrace the risk of higher unemployment in order to reduce the risk of inflation even though the latter hasn’t really been a problem. With the help of the Fed Listens events, the Fed now understands its error and how it inadvertently contributed to persistently high unemployment. The Fed now consistently reminds us that it has learned its errors with talking points such as this from the minutes:

Many participants observed that high rates of job losses had been especially prevalent among lower-wage workers, particularly in the services sector, and among women, African Americans, and Hispanics. A few participants noted that these trends, if slow to reverse, could exacerbate racial, gender, and other social-economic disparities. In addition, a slow job market recovery would cause particular hardship for those with less educational attainment, less access to childcare or broadband, or greater need for retraining.

This language, while accurate, contributes to a perceived negative bias in the Fed’s outlook. Note also that while some of these problems are cyclical in nature (a persistently strong job market will help alleviate the stress on lower-wage households) many are structural in nature. To some (large?) extent, they will not go away entirely even with a strong job market and require fiscal policy fixes. The Fed can’t fix everything. It’s going to be interesting how they at some point explain pulling back on policy when these equity issues haven’t been resolved.

Fourth, the Fed really, really wants more fiscal support for the economy. The Fed, rightly in my opinion, believes the immediate problems facing the economy require a fiscal response rather than a monetary response. My sense is that the Fed’s oft-stated concerns regarding the near-term outlook have more to do about maintaining public pressure on Congress to act rather than signaling a monetary policy response. Market participants, however, I think interpret the Fed as indicating they will attempt to compensate for a failure of Congress to reach a fiscal policy compromise.

Fifth, the Fed insists that its tools remain effective and it will use all available tools to support the recovery. Vice Chair Richard Clarida, recently said:

These large-scale asset purchases are providing substantial support to the economic recovery by sustaining smooth market functioning and fostering accommodative financial conditions, thereby supporting the flow of credit to households and businesses. At our November FOMC meeting, we discussed our asset purchases and the critical role they are playing in supporting the economic recovery. Looking ahead, we will continue to monitor developments and assess how our ongoing asset purchases can best support achieving our maximum-employment and price-stability objectives.

This seems to indicate that the Fed believes that can turn up the dial on asset purchases to support accelerate the recovery (but that’s wrong).

Sixth, the Fed is becoming increasingly aware of the medium-term upside risks to the forecast but often downplays those risks. Chair Jerome Powell, for example, in recent testimony:

Recent news on the vaccine front is very positive for the medium term.

But market participants can be forgiven if they can’t focus on that point given that Powell can’t either as the above points force him back to the near-term risks:

For now, significant challenges and uncertainties remain, including timing, production and distribution, and efficacy across different groups. It remains difficult to assess the timing and scope of the economic implications of these developments with any degree of confidence.

Altogether, the Fed’s messaging has been tilted toward a focus on the imminent downside risks to the economy, a need to avoid anything that might sound like they are revising the path of interest rates, that the economy needs more support, and that they have the tools to further support the economy.

The Fed Minutes Give Clear Guidance

The next step is to take the above communications and link them to the relevant forward-looking policy statements from the November Fed minutes:

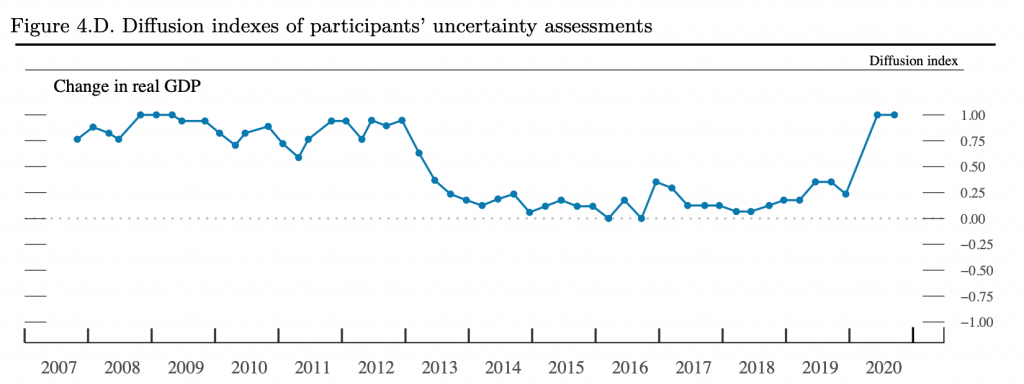

Participants agreed that monetary policy was providing substantial accommodation, and most concurred that, with the federal funds rate at the ELB, much of that accommodation was due to the Committee’s forward guidance and increases in securities holdings. They judged that the current stance of monetary policy remained appropriate, as both employment and inflation remained well short of the Committee’s goals and the uncertainty about the course of the virus and the outlook for the economy continued to be very elevated. Participants viewed the resurgence of COVID-19 cases in the United States and abroad as a downside risk to the recovery; a few participants noted that diminished odds for further significant fiscal support also increased downside risks and added to uncertainty about the economic outlook.

Regarding asset purchases, participants judged that it would be appropriate over coming months for the Federal Reserve to increase its holdings of Treasury securities and agency MBS at least at the current pace. These actions would continue to help sustain smooth market functioning and help foster accommodative financial conditions, thereby supporting the flow of credit to households and businesses. Many participants judged that the Committee might want to enhance its guidance for asset purchases fairly soon. Most participants favored moving to qualitative outcome-based guidance for asset purchases that links the horizon over which the Committee anticipates it would be conducting asset purchases to economic conditions. A few participants were hesitant to make changes in the near term to the guidance for asset purchases and pointed to considerable uncertainty about the economic outlook and the appropriate use of balance sheet policies given that uncertainty.

One way to read this is simply that “more is better.” The Fed believes its policies are effective and that in the coming months they will maintain the pace of asset purchases “at least at the current pace.” The modifier “at least” implies that the Fed is biased toward more easing in the form of alterations to the asset purchase program. Via its communications the Fed has repeatedly agonized over the downside risks to the outlook and the costs of the recession to low wage workers and permanent scarring to the labor markets. By all appearances then it follows easily that with risks of rising Covid-19 cases now realized, the uncertainty of fiscal policy, and the slowdown in job growth in November, the case for revising the asset purchase program is clear. The Fed will thus shift the pattern of asset purchases out toward the longer end of the curve.

If you are happy with that conclusion, you can stop reading here. But another way to read this section is to focus on what the Fed told you is going to happen next:

Many participants judged that the Committee might want to enhance its guidance for asset purchases fairly soon.

Is the Guidance In The Minutes Really Clear?

If you think the Fed is telling us that more easing is coming, a number of questions quickly leap to mind. If the Fed was so concerned about the pace of the labor market recovery and they had the power to accelerate the recovery, why has it not already acted? Moreover, if the reason they maintained the current policy was the risks to the outlook, doesn’t that mean they thought the current policy was too easy in the absence of such risks? With those risks realized, is current policy just right then? Does the Fed really believe that additional policy easing will ease conditions in such a way as to hasten the return to 2% inflation? Clearly given their medium-term forecasts they should already have done so. And what really can the Fed do to improve the economy in the near-term when we know policy acts with a lag?

An Alternative Take

The alternative take is fairly simple. With its focus on the downside risks the Fed has misled market participants into thinking the Fed will take action to counter those risks. The Fed instead see the risks as reason to retain the current pace and pattern of asset purchases but does not believe that anything they do now will help cushion the economy in the critical near-term time frame and is not yet certain whether additional easing is needed or helpful in the medium-term. Moreover, financial conditions are already accommodative and there seems little reason to think they need to be even more accommodative. Some points to consider:

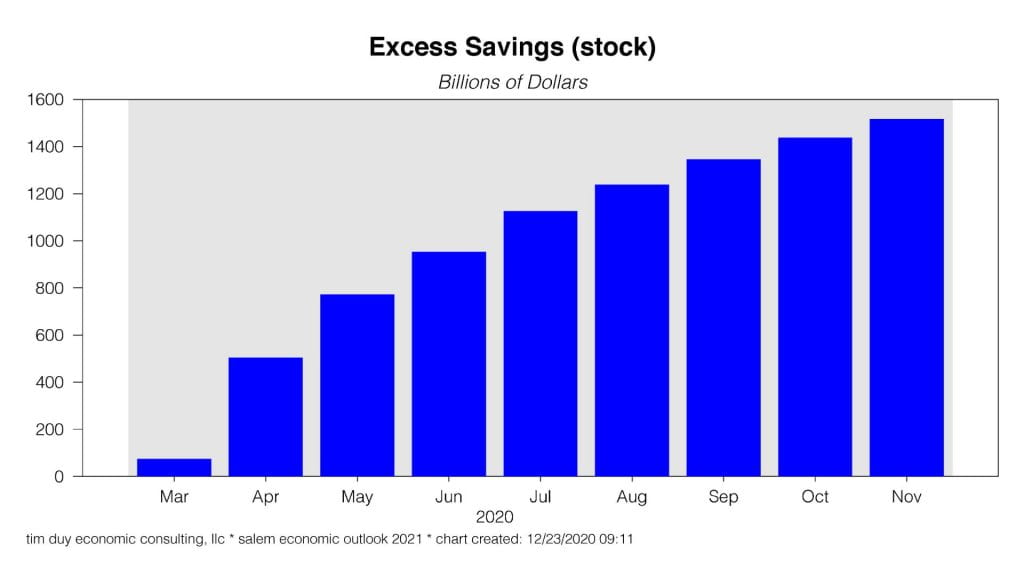

First, with vaccine distribution now imminent, the medium-term upside risks looks increasingly likely to be realized. Everyone expects difficulty for the next two or three months, but the light at the end of the tunnel is now more clearly not an oncoming train. The Fed will have a clearer picture of the economy in just a few months.

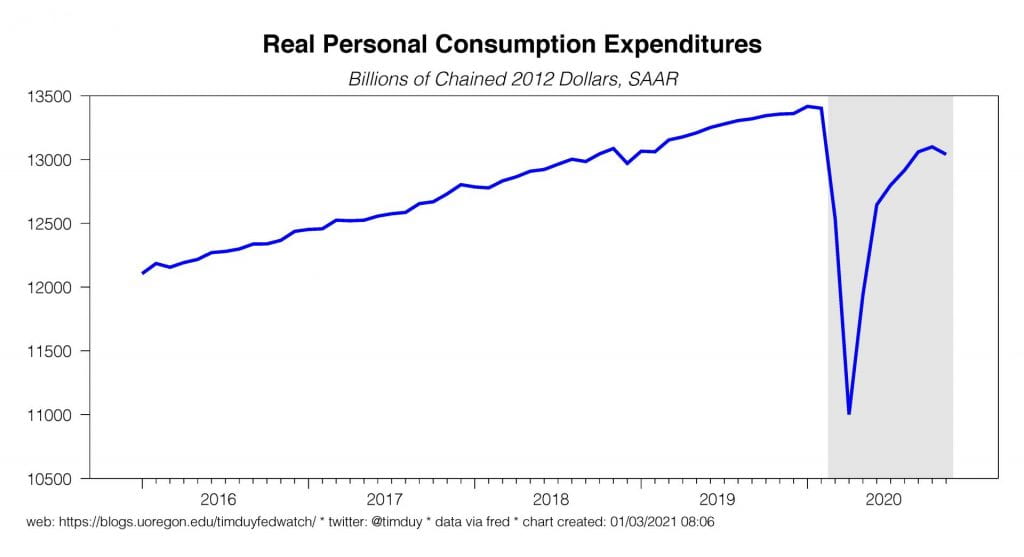

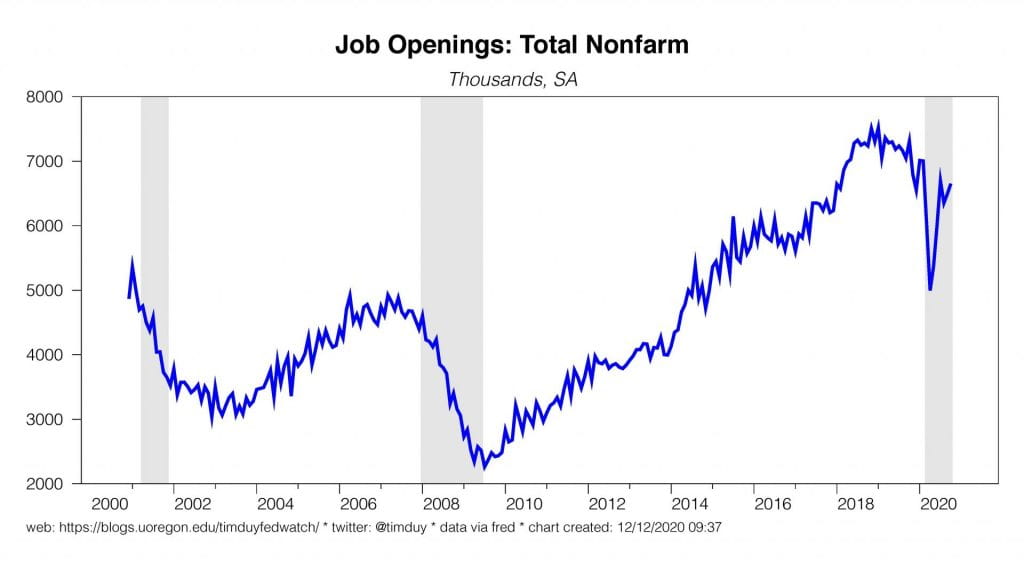

Second, the Fed will be looking beyond the employment report to a wide array of indictors which have been sufficiently positive to drive the Atlanta Fed GDP estimate to 11.2% for the fourth quarter with two thirds of the quarter already complete. To be sure a weak-December will pull this estimate down, but much is already baked in the cake. The economy has more underlying strength and momentum than is commonly believed. Remember, it is not insightful to say the economy is slowing down from the third quarter crazy rebound growth.

Third, the employment report reveals not the weakness of the economy but its potential to rebound. Private sector job growth in November was 344k even after three months of rising Covid-19 cases. Considering the circumstances, that’s a win. Even a flat number for December would be a win in this environment. The Fed must be thinking if we can pull off these numbers with the virus, what is going to happen when the virus is in decline? You should be.

Fourth, if monetary policy acts with a lag, and we all agree it does, easier policy won’t do anything to help the economy right now when it’s needed the most. The Fed can’t do anything to ease the immediate pain. That’s why they want fiscal policy.

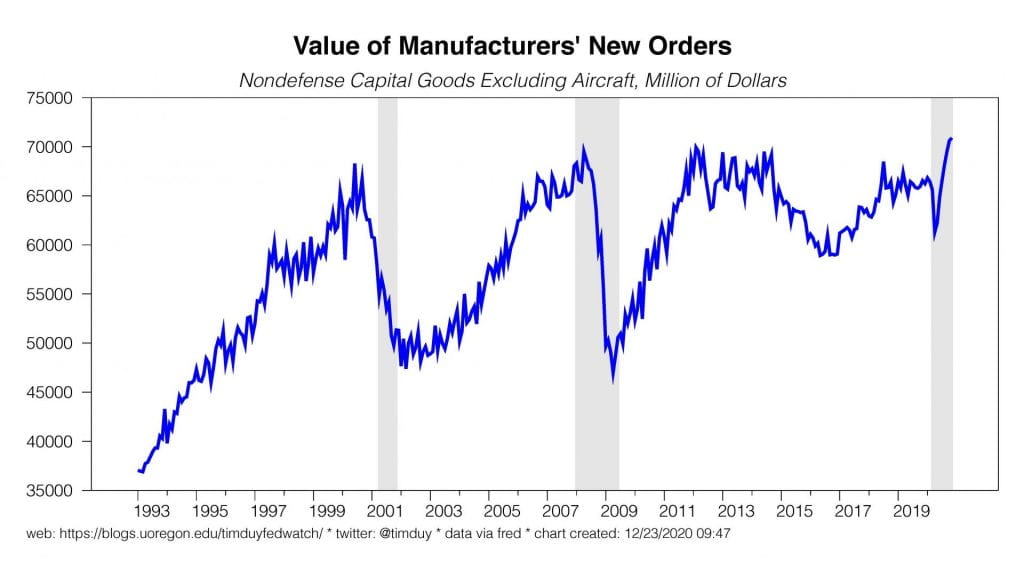

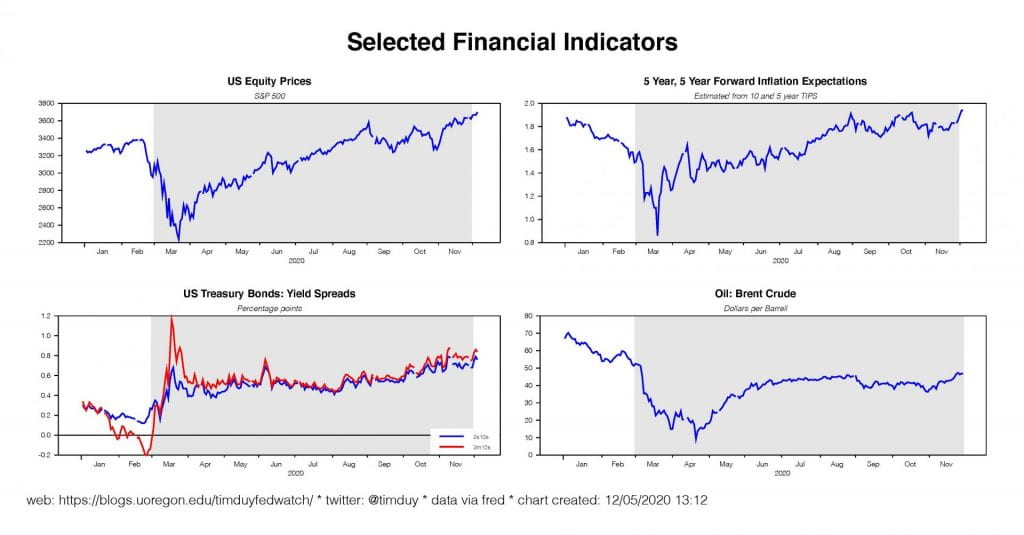

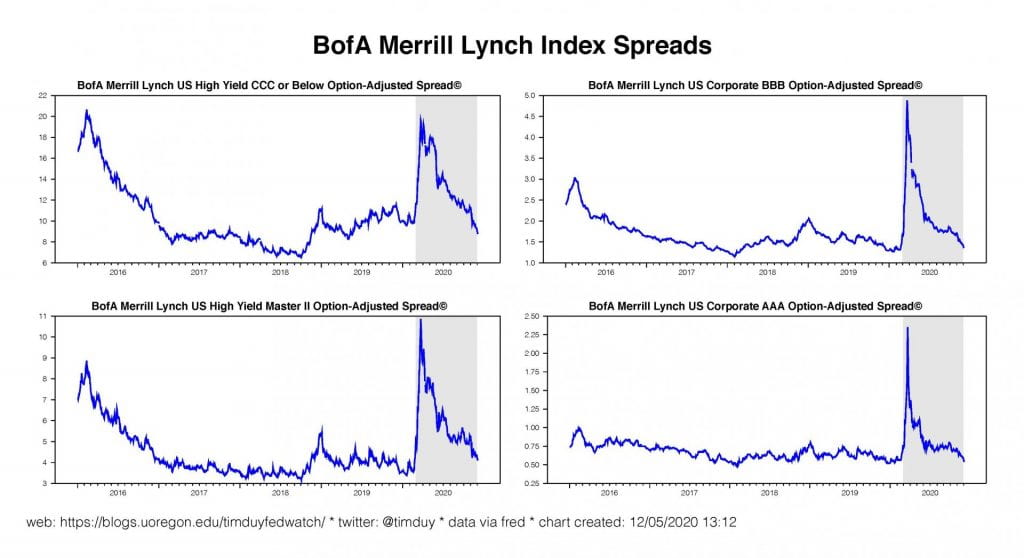

Fifth, there are essentially no signs of tight financial conditions. Financial conditions have been easing pretty much across the board:

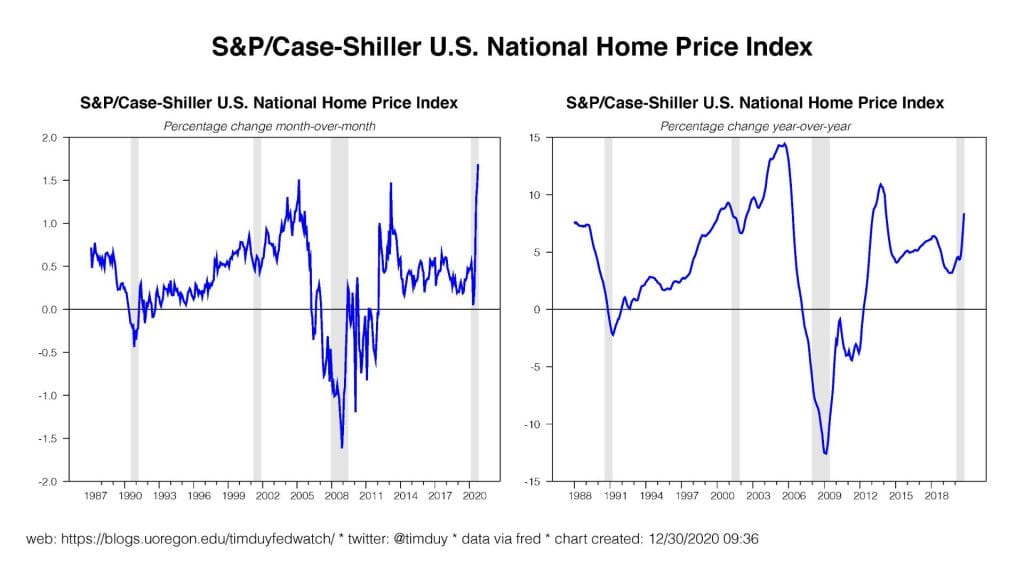

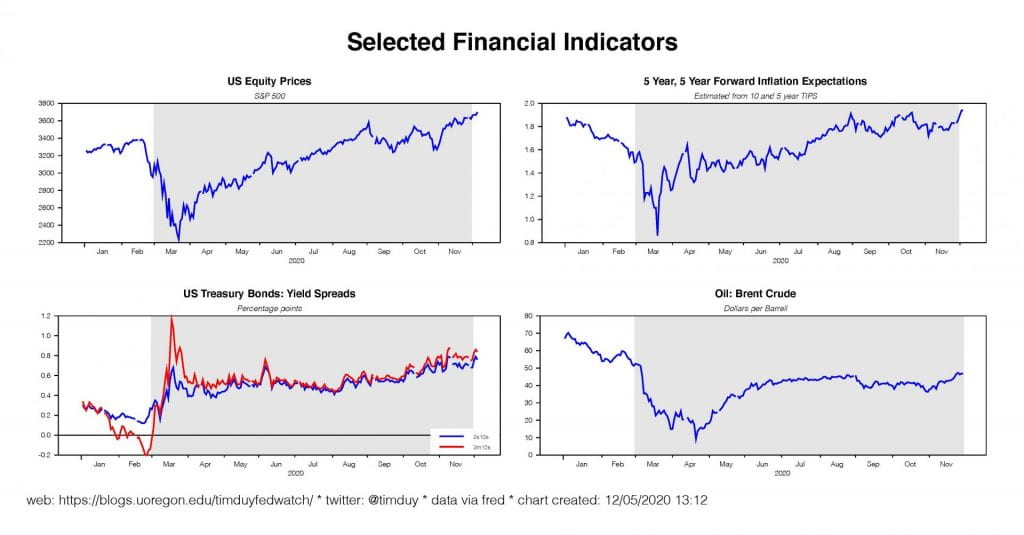

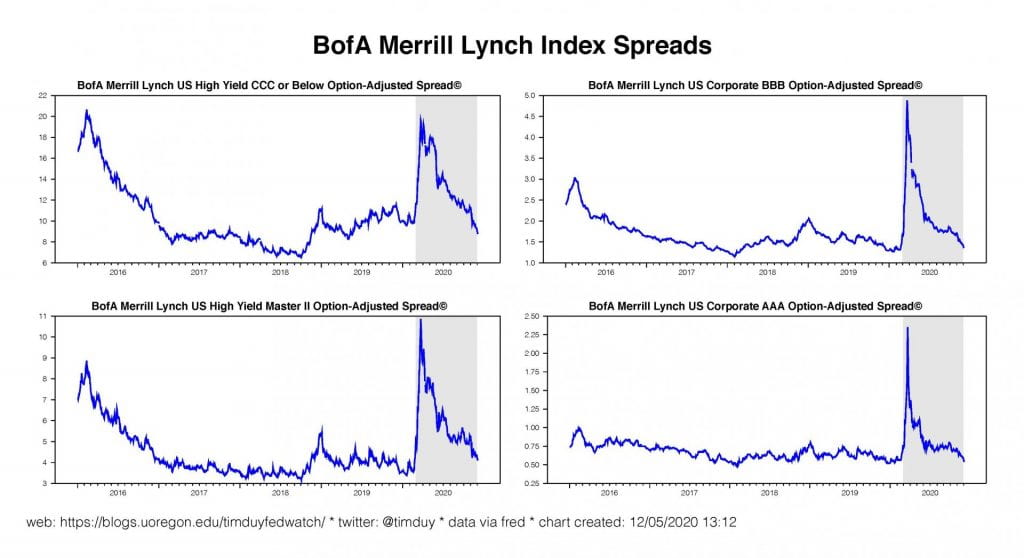

Equity prices are at record highs, inflation expectations have rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, and corporate bonds spreads have fallen to pre-pandemic levels. What is the argument for the Fed to encourage even easier financial conditions? One argument is that the steepening yield curve represents tighter conditions due to rising long-term rates. One might make that mistake given that the Fed has said they can ease conditions by sitting on the long end of the curve. But that is a conditional statement. Never reason from a price change. The Fed will more likely want to sit on the long end of the curve only if they think it stems from a disruption to the financial markets or a “taper tantrum” misunderstanding. Neither appears to be the case now. The most likely reason for a steeper yield curve is rising risk of stronger economic growth in the future. Traditionally, a steepening yield curve is associated with economic improvement.

Sixth, if the Fed really thought they could ease economic conditions further and accelerate the pace of the recovery they should have already done so given its forecasts. The fact that they haven’t done so it fairly clear evidence that they don’t see a great deal of benefit in further easing.

Simply put, an easing next week has little upside and would be only for show.

But Why Hasn’t the Fed Pushed Back On Expectations For More Easing?

I get this question often. If the Fed didn’t like where market participants were headed, why haven’t they stepped in front of that narrative? The problem with this question is the Fed has stepped in front of that narrative, but nobody wants to listen.

Clarida was on November 16 asked point-blank about altering the asset purchase program and to ease financial conditions and reduce interest rates. His answer was I thought fairly straightforward (35:55 mark):

We are buying a lot of Treasuries, we’re buying $80 billion a month, that’s comparable to the pace of QE2 and its roughly the duration pull, so these are big programs, the mortgage program is quite substantial…with long-term yields at historically low levels and below both current and projected inflation, financial conditions are accommodative…we also look more broadly at access and availability to credit and, you know, the corporate bond market is functioning and capital is being allocated…the financial system is really supporting recovery…[story about term structure of interest rates]…an assessment about what the market is telling you, you really need to dig down a little bit…I was not concerned when the yield on the ten-year went from 80bp to 92 or, or whatever, you consider the range that it is in and it certainly still in a very accommodative range.

Clarida saw no need to increase asset purchases or sit on the long end of the curve. He clearly didn’t think additional easing was necessary and conditions have only become easier since then. What more of a signal do you want?

OK, so people want more I guess. But then comes San Francisco Federal Reserve President Mary Daly. Via Reuters:

“It is not the time to stimulate the economy aggressively and get people out in the economy because that would be unsafe,” Daly told reporters on a call after a talk at Arizona State University, held virtually. “I judge policy as in a good place.”

First, Daly is not some kind of hawk. Second, this is a strong position for a Fed president to stake out ahead of the FOMC meeting. Third, that’ some interesting logic. Daly is saying that encouraging more spending now just pushes people into contact with each other. In other words, easier monetary policy actually worsens the pandemic. This isn’t as crazy as it seems. It fits with a view that what the situation really needs is fiscal policy so that we can shut down the economy. Daly continues:

Though the Fed could deliver more support by skewing its $120 billion in monthly asset purchases to longer-maturity securities, Daly said, “I see no indication that markets are misunderstanding where we are headed and that we need to somehow do something different to get financial markets where we need them to be.”

That gets to the idea that the only reason to sit on the long end is if market participants are mistaken about the Fed’s rate path. But there isn’t a problem with market expectations. What might the Fed do instead? It’s already in the minutes, but Daly reiterates:

Though Daly said that giving more guidance on the Fed’s asset purchase program would be a “next natural step” for the Fed, she declined to give any contours of what that guidance could look like.

Ok, so maybe you don’t trust Daly’s signal. She’s newer. She’s on the west coast. I’m on the west coast too. What do we know about what’s going on? Let’s pull another dove then, this time Chicago Federal Reserve President interviewed after the labor report and via Nic Timiraos at the Wall Street Journal. Evans very clearly says they don’t need to revisit the asset purchase program until 2021:

“The risk characterization has improved,” Chicago Fed President Charles Evans said on Friday…

…“As we see progress each and every week and month, that really sets the pace for a better recovery in 2021,” said Mr. Evans. “We’re still looking to see how things are going to work themselves out” before making decisions about whether to provide additional stimulus, he said.

Ann Saphir at Reuters has more from Evans:

“I am not opposed to more accommodation,” Chicago Federal Reserve Bank President Charles Evans told reporters on Friday. But it won’t be until springtime, with the vaccine rollout underway and more clarity on the economic outlook, that “we’ll be able to make the judgment as to exactly what the pace of asset purchases should be, what the duration that we might want to think about taking out should be, and issues like that.”

Back to the Wall Street Journal on what is needed now:

Mr. Evans said he thinks it would be better to revisit any refinements next spring. If growth slows in the coming months, it would be better for Congress and the White House to agree on new relief funding. “Fiscal policy holds the promise to do something more quickly,” he said.

As I said earlier, monetary policy works with a lag. They can’t do anything about the immediate problem. Evans also sees the rise in yields as a positive thing:

“We’re trying to reduce borrowing costs” with asset purchases, said Mr. Evans. “But when the economy is stronger and everybody is demanding more and it’s easier to make good loans at slightly higher payoff rates, that’s actually a good thing for the economy.”

As I said earlier, a steeper yield curve is traditionally an indicator of stronger economic activity. This isn’t some new line of thinking. It’s old as the hills.

So that’s three FOMC speakers that have signaled that the Fed isn’t prepared to change the asset purchase program. A fourth is Dallas Federal Reserve President Robert Kaplan (a voting member). In an interview with the Nick Timiraos of the Wall Street Journal, Kaplan says his near term focus is on the financial markets:

What happens beyond the first quarter of next year will be something that we’ve got to be very cognizant of in thinking about the stance of monetary policy. So in the short run, I’m going to be monitoring to make sure that we don’t have a negative change in financial conditions so that we can help get through this next three to six months. But over the horizon, assuming that doesn’t happen, I’m more focused over on recovery heading into next year.

Again, all the Fed can do right now to support the economy is to ensure that financial conditions don’t tighten. And conditions are loose. Asked point-blank about changing the asset purchase program, Kaplan gives a straight answer:

WSJ: So assuming that financial conditions do not tighten in some extremely unwelcome way, would that call them for just keeping monetary policy where it is over the next three to six months?

KAPLAN: Yes, I think for now, there are some issues we’re going to have to decide on. What is appropriate timing of forward guidance regarding our asset purchases? We’ll have to decide when it’s appropriate to give that communication. Otherwise I’m not inclined to make changes to the stance of monetary policy unless there’s some change in the short run.

Think this through: Evans, Daly, and Kaplan were all at the November FOMC meeting and knew where the discussion was heading. Do you think any of them, especially noted doves Evans and Daly, are staking out super-strong hawkish positions relative to expectations in the week ahead of a controversial FOMC meeting when they expect to be on the losing side of the debate? Or do you think that they are staking out super-strong positions ahead of an uncontroversial meeting when they already know the outcome and want you to know the outcome? Do you really think they are playing some kind of three-dimensional chess by misleading us? And is it a coincidence that Evans stakes out that position literally the day before the blackout period begins?

None of this seems that hard. The Fed kind of screwed up the communications with all the emphasis on downside risk. They didn’t spend enough time explaining that the downside risk was very short-term and they really couldn’t do anything about it. They didn’t spend enough time saying that their tools are still powerful in response to a tightening of financial conditions but the economy fell into a deep hole and they can’t do much beyond create accommodative financial conditions that allow the economy to heal but that healing takes time. They have spent time explaining the importance of fiscal policy in the near term but haven’t until last week explained they couldn’t compensate for a lack of that policy because monetary policy works with a lag and by the time it kicks in we will be on the other side of the surge. That said, last month Clarida was very clear that financial conditions were accommodative and that more wasn’t necessary. I don’t know that anyone was paying attention.

Bottom Line: I don’t have some secret source that is telling me what is going to happen next week and I understand the inclination to think more easing is coming but I really don’t like predicting something that is the exact opposite what multiple Fed speakers are saying. It seems to me that the Fed is telling us they are going after the low-hanging fruit of putting some guidance on the asset purchase program at this next meeting. The Fed did discuss in November potential changes such as the duration mix or the size of asset purchase but this discussion regarded policy beyond the current surge of Covid-19 cases. With financial conditions currently easy and the Fed literally unable to impact near-term economic outcomes, there doesn’t seem any reason to change policy next week. Of course, an unexpected tightening of financial conditions would be something that the Fed could address should that occur between now and the meeting.