Pulp Time Machines: Flash creator Gardner Fox’s comics collection

The past meets the present in our Friday File series, where we delve through artifacts housed at the UO Libraries and let them talk.

He created the Flash, molded Batman, and wrote the first Justice League comic, but Gardner Fox didn’t care about being famous. That’s why his name isn’t in many of the more than 600 comics in Special Collections and University Archives.

“He believed in comics,” said Jennifer DeRoss, a University of Oregon Master’s student in English who has studied Fox. “He supported the genre of comics itself. Fame wasn’t important to him.”

Fox could have been famous; entering the field at its infancy in the Golden Age, Fox began writing even before Action Comics #1 and Superman’s debut. His contributions to the fledgling cultural phenomenon put him in a category with Bob Kane, Stan Lee, and Jack Kirby.

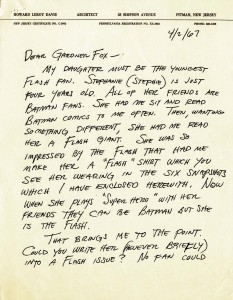

In 1967, Fox contributed old comics, notes, scrapbooks, and letters to the University of Oregon, creating SCUA’s Gardner Fox Papers. The Gardner Fox Papers provide not only artifacts from the Golden Age of a modern cultural phenomenon, but a unique look into one of the men who shaped generations of imaginations.

Fox practiced law, but jumped into comics writing on the tail end of the Great Depression to supplement his income. After Action Comics #1 came out, the genre exploded: In just six years, more than 700 costumed crimefighters popped into the world, according to Ben Saunders, founder and director of UO’s Comics and Cartoon Studies minor. The industry needed people who were somewhat creative and very prolific.

Fox was both. In his life, he wrote more than 4,200 comics with more than 100 characters, as well as more than 140 books. There wasn’t a genre he wouldn’t write, from science fiction to detective stories and even porn. This made him an ideal superhero creator, according to Saunders.

After their debut, superhero stories quickly became an intersection of genres. They blended Greek myth with science fiction, or detective stories with spy thrillers, or sword and sorcery with crime stories.

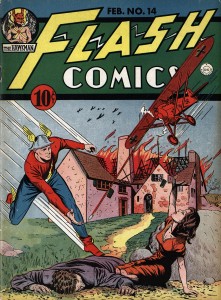

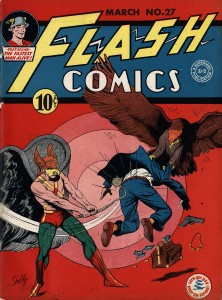

In the spirit of genre-bending, Fox took Batman in his third issue and gave him his utility belt, a “Batarang,” and his first flying machine. Fox took his love for archaeology and Egyptian myth and created Hawkman. And, in a creative move that secured his place in comics history, he took inspiration from the Roman god Mercury, added a lab accident, and created the Flash.

“He tended to make things more magical, insert more science,” DeRoss said. “It’s hard to get out from under the influence of Fox.”

Fox also built ideas that would define comics writing, introducing parallel universes and superhero team-ups to comics. He was the first writer on the Justice League of America strip.

(The one big blot on Fox’s record, Saunders said, is that he made Wonder Woman the Justice League’s secretary.)

Fox was constantly coaching himself to write better. His collection is full of notebooks punctuated with notes to himself like “My characters must be HUMAN!”

Comics, at the time, were sold in packages: A superhero story would be sold couched between a detective story and a jungle tale or a domestic comedy and a horror piece. These packaged comics aren’t saved anywhere but in Special Collections, Saunders said.

“The most valuable thing about the collection is the prints,” Saunders said. “They’re pulp time machines.”

Information for this article was collected from the following source:

Scott Greenstone

Student Editorial Assistant

UO Libraries

Are any of the notes (plots, unsed scripts) scanned? most of his comics are already on line.

Thanks for the interest, Lawrence. None of the collection items are currently digitized. Information on requesting digitization is available on our website here: https://library.uoregon.edu/digital-library-services/digitization