Behind the Scene: Processing President Dave Frohnmayer’s Papers

This blog post highlights the recent project to complete the processing of Dave Frohnmayer’s presidential and personal papers by Caroline McNabb, Project Archivist, who took over the processing project after several staff and students previously completed most of the accessioning, preliminary inventory, and initial arrangement. The Special Collections and University Archives staff wish to thank Caroline and the entire staff and students for their hard work and dedication to this project.

This blog post highlights the recent project to complete the processing of Dave Frohnmayer’s presidential and personal papers by Caroline McNabb, Project Archivist, who took over the processing project after several staff and students previously completed most of the accessioning, preliminary inventory, and initial arrangement. The Special Collections and University Archives staff wish to thank Caroline and the entire staff and students for their hard work and dedication to this project.

__________________________

About the Collections

Dave Frohnmayer is a University of Oregon Law professor, former dean, and the 15th President at the University of Oregon, among other varied career arcs. He has been active on our campus for over 40 years, from his first year teaching in 1970 to his last year as President in 2009—and is currently back to teaching his popular Freshman seminar, “Theories of Leadership.”

His archival materials have been separated into two collections: Faculty papers and Office of the President records. The faculty papers collection spans Mr. Frohnmayer’s entire life and includes materials from his tenure at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; three terms as State Representative; UO professorship; Special Assistant to two UO Presidents; three terms as Attorney General; one unsuccessful campaign for Governor; and Dean of the School of Law. Besides this dizzying array of professional artifacts, the collection also includes a wealth of personal materials, including family photographs and items from his childhood.

The Office of the President records focus exclusively on Mr. Frohnmayer’s tenure as President of the University of Oregon, beginning in 1994 and ending in 2009. Materials include speech transcripts, recordings, and notes; documentation of various campus controversies and important issues; administrative materials, and an incredible assortment of visual and audiovisual materials. This collection documents Mr. Frohnmayer’s Presidential work, but is also a slice of University history. Of particular import is the fact that the Internet emerged in the early years of his presidency, so communication and information dissemination was rapidly changing during this time.

Processing Work

Processing work involved inventorying each box, intellectual organization, preservation, and researching David Frohnmayer and the cultural-historical events of the time periods. I began by conducting a thorough inventory of the dozens of boxes located at Knight Library and the Baker Downtown Center. Some boxes came with contents lists from Mr. Frohnmayer’s secretary, Carol Rydbom, but many of these were no longer accurate, since materials had been shifted since donation. Looking through these boxes—some quite old and mysterious—was akin to an archaeological dig or detective work. I found surprising, fascinating items and learned a lot about University history and Mr. Frohnmayer’s life.

Once I had a handle on exactly what the materials were, I organized them by time period, theme, and collection. I used a spreadsheet for this, and spent many hours moving items around and arranging them into series and subseries. This method of sense-making is called “intellectual organization,” and is very important to make a collection understandable and accessible.

While going through the materials, I came across a great many items that had preservation concerns—photographs rubbing against each other in envelopes, rusty staples—even some insects! I took note of preservation needs and took care of the most egregious concerns. Sadly, some items had to be deaccessioned (removed) due to their poor condition.

Finally, I began researching David Frohnmayer’s life in order to better understand his career paths, motivations, personal life, and family history. I used this data to begin writing what are called scope notes—contextual information on a finding aid that gives researchers insight into the history, value, and meaning of the materials in a collection. Many times throughout this process I learned something interesting that changed my perception of some portion of the materials.

Challenges

The major challenges I came across during processing were related to preservation and intellectual organization. Some larger visual materials had been tightly rolled for years and needed to be flattened; I had the opportunity to learn some new preservation strategies. In addition, it was sometimes difficult to select the proper enclosures for different items. Should I use a buffered paper envelope or a polymer pouch? A flat museum box or an upright manuscript box? Luckily, most of these questions were answered by looking at archival best practices documentation, but there were times that I had to use my best judgment.

In terms of intellectual organization challenges, there were several items that could have gone in either collection. I had to really consider the historical context, surrounding materials, and how they were used to determine whether the Faculty papers collection or Office of the President records collection was more appropriate. David Frohnmayer’s career has been incredibly complex, and there was a lot of overlap with personal and Presidential materials. I hope that researchers take the time to peruse both collections to get a good idea of the work he did.

Successes

Successes were far more significant and satisfying than the challenges. I located interesting and important items that nobody knew were in the collections. I personally learned a lot about Mr. Frohnmayer and University of Oregon history and am excited that future researchers will have the chance to do the same. I had the opportunity to collaborate with several librarians to discuss best practices and explore processing strategies. And my favorite part: that moment when the intellectual organization came together and the disparate materials suddenly made perfect sense.

Items of Note

There are so many interesting items in the Frohnmayer collections, including a beautiful wooden scrapbook from one of the Attorney General campaigns, an adorable 1st grade class photo, songs that Mr. Frohnmayer wrote and sang at various events, photographs with President Bush from a National Association of Attorneys General trip, photographs with Tom Cruise from the “Without Limits” movie premier in Eugene, a historical essay about the beard styles worn by early University of Oregon professors, and materials documenting various campus controversies.

Here are just a few of my favorite items:

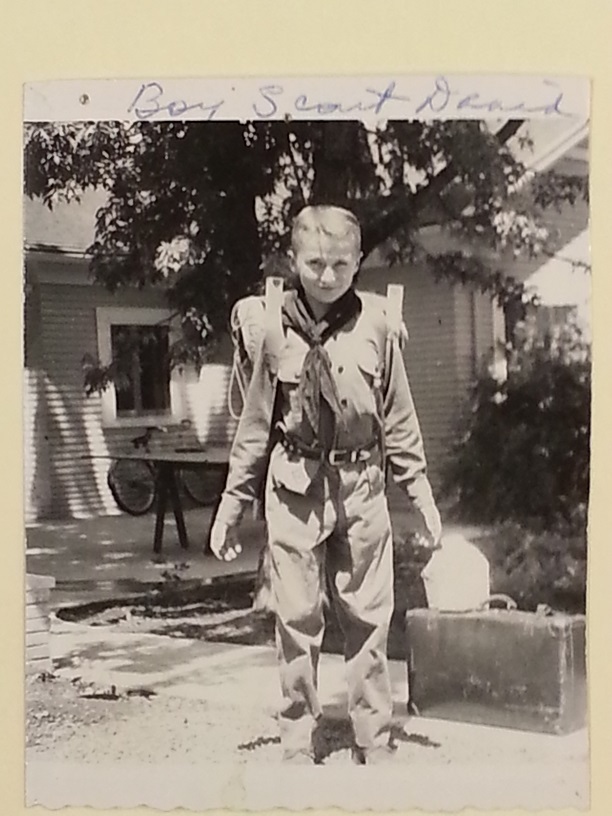

Here is a delightful undated photograph of a very young David Frohnmayer in his Boy Scout regalia.

As a high school student in 1957, Mr. Frohnmayer took a trip to Hamburg, Germany through the American Field Service program.

This intriguing event program is from a satirical play put on by Mr. Frohnmayer’s law school cohort.

This black and white photograph was taken during Mr. Frohnmayer’s first year of teaching at UO, in 1970.

Here are several pieces of ephemera from Mr. Frohnmayer’s Attorney General campaigns.

To celebrate the University of Oregon’s 125th anniversary, several staff members collaborated on a commemorative quilt, which was finished in September 2001.

What’s Left

There is a lot left to do to process these collections—physical organization, rehousing, preservation measures, and creating finding aids. Each box has a mixture of materials, sometimes from entirely different series and even from different collections. Since most of the time a researcher is interested in exploring a specific theme or time period, these collections will be more easily accessible if materials are physically organized in alignment with the intellectual organization. Along with this, most boxes are in poor condition, so materials require new boxes as well as new folders (which have to be properly labeled). The preservation concerns that I highlighted will need to be taken care of at this time, as well—housing photographs in archival enclosures, removing rusty fasteners, interleaving delicate items with tissue paper, selecting appropriate boxes for unusual sizes and shapes of materials, and so forth. Finally, robust finding aids need to be created using the spreadsheets and scope notes. All of this work will ensure that the materials remain in good condition and are described to a level that will help researchers locate and interpret them.

~Caroline McNabb, Processing Archivist