Ronald Emick III

ENG 486

Professor Fickle

3/21/17

The Mass Effect Theory

Literature and film have often been used to discuss controversial issues, and even influence the public’s opinion on the matters, pushing a society’s culture towards radical ideas and away from old ones. Video games have been doing the very same thing, and the Mass Effect trilogy is a perfect example of this. Each of the games has generated controversy around the charged topics that they discuss, and it’s up to the player to decide how to handle the situations. During my last play through of the games, I took time to think about just how many issues from the real world that have been re-framed within Mass Effect’s universe, and it is staggering. I found myself making moral decisions on the justification of genocide (in multiple differing situations), AI and its relationship to organic life, heterosexual/homosexual relationships, human and alien relationships, elitism, racism, sexism, speciesism, gender fluidity, genetic modification, and ultimately the death of life as the galaxy knows it. And I left twice as many smaller issues out of that list. All of this packed into three games of fast paced third person shooting across the galaxy to save it from destruction via Reapers (more on them later). I will discuss several of these issues as they appear in the games, and their implications in the real world, as well as why Mass Effect is the perfect game space for the discussion of these big issues.

The Mass Effect universe is a violent place, with one form or another of conflict always taking place. Throughout the course of the series, genocide is a recurring topic, and the narrative forces the main character, Commander Shepard, into deciding whether it is justified in differing situations. During a mission in the first Mass Effect game, Shepard must decide whether to kill the last remaining queen, and only hope for the Rachni species. The complication here is that five hundred years’ prior, the Rachni had waged galactic war, and nearly annihilated all the other spacefaring races. So, the moral question becomes “do you kill the last hope of an entire species for mistakes that are still felt five hundred years later, or do you give them a chance to redeem themselves, despite a violent history?

Rachni Queen awaiting Shepard’s Judgement:

Link to Video: https://youtu.be/IymgIxeRskw?t=7s

The second game in the series presents the issue of Genocide multiple times, in the form of both the Krogan and the Geth. The Krogan were the race that saved the galaxy from the Rachni all those years ago, but their warlike culture (and massive birth rates, considering in a single birth, there can be a thousand children) led other races to fear that they would turn around and destroy the other races. In response to these fears, to keep the Krogan population in check, two races (the Salarians and Turians) designed a genetic modification (known as the genophage) that altered the viable birth rates of the Krogan, so that only a few in their millions of births survive. The Salarians see this as a simple adjustment of fertility, but most of the other races, the foremost being the Krogan, see this act as a form of genocide. Mass Effect 2 has you team up with one of the scientists who help modify the genophage, which naturally leads Shepard into a heated debate over whether this act was justified or not. The third game then puts the player into the position of deciding to cure the Krogan of the genophage, or letting them continue to have the genophage. Again, Bioware is asking the player whether this form of genocide is justifiable or not.

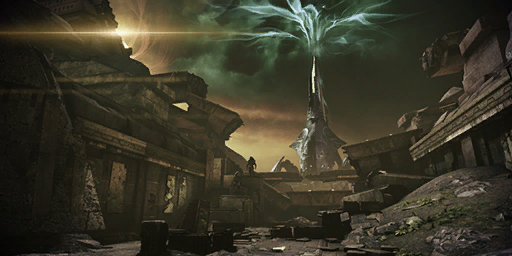

The location where Shepard can choose whether or not to cure the Krogan of the Genophage.

Link to discussion about the Genophage: https://youtu.be/W0vFvEgZpXk

Lastly is the issue of the Geth, a race of machines that had been designed by Quarians, but their AI became too complicated and they began asking questions about the nature of themselves (for example, “Does this unit have a soul?”). They are the main antagonist faction during the first game, ensuring that the player has major grievances with their kind when entering the second and third games. However, things change when you discover that they were the victim in their conflict with the Quarians, and manipulated by outside forces in the first game. When the player makes it to the third game, they are asked to decide between sacrificing the Quarians or the Geth in the interest of gaining the other one for an alliance. Yet again, the question is being asked, is genocide ever justifiable, even if it is an AI race that you have understood as a bad guy for a significant portion of your experiences in this universe?

Legion (one of Shepards Companions) and his fellow Geth Primes.

Link to video about the destruction of the Geth: https://youtu.be/PTmhVLj807U

Mass Effect works to not only push the player to make hard decisions in regards to warfare, but also works to push the player into having relationships with other characters. But these aren’t your standard “man and woman” relationships. Those certainly are there, but they are in the minority. A player has the option to romance the same sex, and even alien races. Each character that can be romanced has their own sexuality, some being straight, some homosexual, and some bisexual. This implies that “Mass Effect’s stance on gender and sexuality is not always straightforward, [and] is clear that the concept of race [and sexuality] becomes meaningless in the future” (Zekany 71)

Garrus and Tali: Two alien romance options for Shepard.

Link to video of the initial Tali romance discussion: https://youtu.be/1Y1bVZI6A9g?t=34s

. This attitude even extends beyond romance, and into forming friendships and attachments to things that would have been deemed unacceptable in the first game. Despite AI being the main antagonist throughout the games (namely the Reapers), “The player depends upon one [Artificial Intelligence] … and may even form an emotional attachment to it” (Geraci 744). These relationships and interactions with characters often result in changes to main story line, including party banter, or even endings being changed. A great example of this is in Mass Effect 2, Shepard can go on “loyalty” missions that each of his companions have, and depending on how the missions play out, Shepard will secure the character’s loyalty. Doing so will make it more likely that the player will succeed at the final mission. This suggests that these relationships are vital to the player’s experience, seeing as how if a player doesn’t secure every character’s loyalty, it is likely that one or even the whole team will die.

Members of Shepard’s crew during Mass Effect 2.

Link to video of Loyalty Mission for Garrus: https://youtu.be/Ezih2ausUA4

The evidence suggests that there certainly are a whole host of controversial issues discussed within these games, but why would the Mass Effect universe be a space that works so well for presenting these issues and then discussing them? I believe this for a couple different reasons. First, it is the design of the game to allow the player to make their own choices and make their own moral judgments about the issues. Another way to put this, as stated by Jenifer Martin, “players are seen to experience self-expression and agency through the narrative structures and design strategies of the game” (Martin 344). The game simply presents you with the issues and the opposing sides of the argument, then drops the player into a situation where they must make a judgement. As applied to the issue of sexuality, “I [the player] was faced with dialogue choices that allowed me to enact my sexual orientation [or that of my choosing]” (Kuling 44). The key words here are “choice” and “self-expression”. These games act as portals through which a player can make their judgments about these issues, and then see their decisions take shape in the form of consequences (for example if Shepard fails to secure the loyalty of a group member, and then they die during the last mission because of this). The game even goes as far as letting the player choose in what order they want to experience these events (except for certain key missions). This is shown through the galaxy map, “a map nominally located on the bridge of the space ship Normandy… used to travel to different locations and start or continue missions” (Punday 94). {[Insert Pic]} If certain missions are played after others, then the way that they play out is different, sometimes having dire ramifications on the final mission or even subsequent games. My second reason for seeing this game as the perfect space for these discussions is the fact that this game is a science fiction game set in a “speculative future”. This game makes its on timeline that links to the real world, and speculates how the future would unfold in a “what if” scenario. This allows for the game designers to take issues from our current time-period, and rework them in the context of the Mass Effect universe. This reason, however, is critical to the discussion of why I am even writing about this.

These games work hard to create a space the breeds and hosts controversial issues, and allows players to discuss them in an isolated environment, free from the judgments of anyone other than what the game provides. Through the discussion of these issues the player is allowed to create their own “ideal future”, where what they think of as right, becomes reality. This “utopia creation” allows a person to explore their viewpoints, and since the world of Mass Effect is very imperfect, their decisions are likely going to result in further imperfection. It essentially acts as a moral choice simulator and results generator. The creation of a true alternate space, while still being tied to the real world in a proposed future, that discusses these issues. This “distancing” of the issues through time allows for the discussion of these issues, without becoming so politically and emotionally charged. This allows for true exploration of the subject.

Additionally, Mass Effect shows a change in the way that culture shifts through literature. In books and movies (and certain games that feature completely linear story lines), viewpoints are expressed by characters other than the readers, and these viewpoints affect those who read it and have differing opinions. It gives exposure to outside opinions. However, this affect is only limited to those who have differing opinions. Mass Effect is unique from other things because it allows the player to make moral judgments and then see the results, the impacts, the consequences of these decisions. It allows a player to see both sides to an argument, where in one play through they choose one option then the next they choose the other. This means that literature can literally show what the players (instead of the characters) think and what judgments they would make about these issues.

This space of experimentation within Mass Effect is a place that few video games can successfully create, but without this form of narrative, video games will always be limited to the same linear style of storytelling, found in books and movies. The interesting thing is that Mass Effect is often referred to as a “cinematic” experience, and yet the way in which it allows the player such agency is the exact opposite of a “cinematic” experience. With Mass Effect Andromeda slated to come out in days, and boasting a story line about expansionism and creating new colonies in a new galaxy, the discussion of how these games interact with modern life and the issues of the times is critical, and ultimately a welcome thing where open discussion is so hard to have.

Works Cited

Bioware. Mass Effect Companions. Digital image. Arstechnica. Arstechnica, Mar. 2013. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Conlin, Dan. Races Geth. Digital image. N7 Follower. Mass Effect Follower, 17 Feb. 2015. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Cullen, Simon. Mass Effect 2 Party. Digital image. The Aculeus. Blogspot, 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Geraci, Robert M. “Video Games And The Transhuman Inclination.” Zygon® 47.4 (2012): 735-56. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO]. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Kaiser, Rowan. Garrus and Tali. Digital image. Unwinnable. Unwinnable, 14 Apr. 2014. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Kuling, Peter. “Outing Ourselves in Outer Space: Canadian Identity Performances in BioWareâs Mass Effect Trilogy.” Canadian Theatre Review 159 (2014): 43-47. Project MUSE [Johns Hopkins UP]. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Martin, J. “Game On: The Challenges and Benefits of Video Games.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 32.5 (2012): 343-44. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO]. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Mass Effect 2 & Mass Effect 3. Prod. Bioware. Mass Effect: Complete Tali Romance. DanaDuchy, 28 July 2014. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Mass Effect 2. Bioware. January 26, 2010. Video Game

Mass Effect 2. Prod. Bioware. Mass Effect 2 – A Discussion with Mordin on Genophage. ArchiBarrel1991, 25 Feb. 2013. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Mass Effect 2. Prod. Bioware. Mass Effect 2: Garrus Loyalty Quest – Saving Sidonis. Shepardcousland, 28 Jan. 2010. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Mass Effect 3. Bioware. March 6, 2012. Video Game.

Mass Effect 3. Prod. Bioware. Mass Effect 3 – Letting the Geth Die. J.C.’s Channel, 28 Apr. 2012. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Mass Effect Andromeda. Bioware. March 21, 2017. Video Game.

Mass Effect. Bioware. November 16, 2007. Video Game

Mass Effect. Prod. Bioware. Mass Effect Paragon & Renegade Rachni Queen SPOILER. Kl1n3, 19 Dec. 2007. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Noveria Rachni Queen. Digital image. Mass Effect Wikia. Wikia.com, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Priority Tuchanka. Digital image. Mass Effect Wikia. Wikia.com, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Punday, Daniel. “Space across Narrative Media: Towards an Archaeology of Narratology.” Narrative 25.1 (2017): 92-112. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO]. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Zekany, E. “”A Horrible Interspecies Awkwardness Thing”: (Non)Human Desire in the Mass Effect Universe.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36.1 (2015): 67-77. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO]. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Thank you, good article.

–

Lesbian News

Ankara Antikacıları

Thank you for the information . Sewa mobil banyuwangi

Thanks for your information REPUBLIKGAME

Originalitatea este un aspect esențial în elaborarea lucrărilor academice. Universitățile și instituțiile de învățământ superior pun un accent deosebit pe produsele originale ale cercetării, având în vedere că plagiatul poate duce la sancțiuni severe, inclusiv respingerea lucrării sau exmatricularea pentru lucrare de licență plagiata.