In the past twenty years, the co nsumption of Japanese products in America has grown exponentially, and the consumption of its food is no exception. However, it is not simply the food that is desired in the West – it is the aspect of Japanese “cool” that surrounds it. In his article “Japan’s Gross National Cool,” Douglas McGray writes that Japanese products are desirable because they contain a “whiff of Japanese cool,” meaning they have something novel, something “Japanese,” that makes them more attractive to the West. This “Japaneseness,” whether authentic or not, is what is desired and paid for in the West as much as the food itself. Through examining the way Japanese food-related products are marketed and perceived in the West, one may see that while the food may be delicious, it is the “whiff of Japanese cool” that strongly appeals to Western tastes.

nsumption of Japanese products in America has grown exponentially, and the consumption of its food is no exception. However, it is not simply the food that is desired in the West – it is the aspect of Japanese “cool” that surrounds it. In his article “Japan’s Gross National Cool,” Douglas McGray writes that Japanese products are desirable because they contain a “whiff of Japanese cool,” meaning they have something novel, something “Japanese,” that makes them more attractive to the West. This “Japaneseness,” whether authentic or not, is what is desired and paid for in the West as much as the food itself. Through examining the way Japanese food-related products are marketed and perceived in the West, one may see that while the food may be delicious, it is the “whiff of Japanese cool” that strongly appeals to Western tastes.

The growth of Japanese cuisine’s popularity in America can be easily tracked over the last few decades, with the surge of Japanese food in the West beginning near the crash of Japan’s “bubble economy” in the early 1990s. The loss of economic power was replaced with cultural dominance in other countries, and Japanese food in the West is an example of Japan’s increased presence in foreign markets. According to Ray Isle in his Food & Wine article “Sushi in America,” the number of sushi restaurants has quintupled in 1988. Benihana, one of the most well-known Japanese steakhouses in the United States, grew from twenty restaurants to eighty-eight since 1995.

Benihana, a Japanese steakhouse chain founded in New York in 1964 by Tokyo-born Rocky Aoki, exemplifies the success of utilizing Japanese cool in the marketing of a product, even if the product may not be essentially Japanese. On the company website, Benihana restaurants are called “traditional Japanese hibachi steakhouses.” However, the first teppanyaki-style restaurant in Tokyo, Misono, was not founded until 1945. Even then, such steak houses in Japan were meant to cater to foreigners (Steinberg 157). Currently, teppanyaki cooking in Japan is most often a “do-it-yourself” process in which the diner is responsible for cooking his or her own food.

Despite the lack of authenticity of Japanese steakhouses in general, Benihana places a strong focus on its roots in Japanese culture. Customers are not simply paying for food – they are paying for the Benihana “experience,” which the company asserts is very Japanese. The company has an entire section of its website devoted to the aspects of the restaurant that are seen as Japanese in nature, from its use of bamboo in its tables to the chopsticks offered to guests. The over-the-top performances of their chefs are said to be inspired by “the art of performance” in Japan, with a paragraph about Kabuki following even though Kabuki has little to do with the spatula-swirling and onion volcanoes associated with the restaurant. The attempt establish a sense of Japanese tradition extends even further, as one even sees Japanese steakhouse chefs being compared to samurai or ninjas, with various videoson Youtube promoting that image. While the “Japaneseness” of these restaurants is often vague or even manufactured, such aspects are emphasized because they appeal to the consumer of Japanese cool.

The description of Japanese cooking in books and articles targeted towards Western audiences also contributes to this desirability of Japanese foods. Traditional Japanese cooking is almost always presented as mysterious, beautiful, ancient and even spiritual in these texts, as exemplified in Byalan Brown’s article “Zen Palate.” He describes a trip to Kyoto, which he praises as a picturesque “window to the past,” with architecture, traditions and cuisine infused with the spirit of Zen Buddhism. He focuses on the kaiseki, the multi-course meal served to tea ceremony attendants. The cuisine and customs are regularly contrasted with the West – the portion sizes are tiny in comparison, Western dishes are dull and unimaginative compared to the seasonal Japanese ones, the slurping of tea is polite — all the while painting Japan as an exotic and novel place where food is characterized by exotic practices and spiritual traditions. These exotic perceptions transfer over to the Western consumer, who may feel more tied to Japanese traditions when they pick up their chopsticks to eat sushi at a high-end restaurant.

Sushi, and to a lesser extent other traditional Japanese cuisine, has become associated with sophistication and a higher social class. On the website Stuff White People Like, an entire section is devoted to poking fun at the “yuppie” culture’s regard for sushi. In the article, the food is described as exotic, expensive and only appealing to those who are educated enough to truly understand it. An individual’s taste in sushi places them in a sort of class hierarchy, with those who simply buy California rolls at Trader Joe’s at the bottom and those who speak Japanese when they order at sushi bars at the top. A large part of sushi’s appeal, as it is presented in the West, is that it can be enjoyed only by those worldly enough to comprehend its intricate nature and the culture that surrounds it.

Multiple books are devoted to teaching Westerners about sushi, claiming that upon finishing the work, the reader will be versed in the art of sushi to impress all their acquaintances with their extensive Japanese culinary knowledge. Dave Lowry’s The Conoisseur’s Guide to Sushi promises to take those truly interested in learning the mysteries of sushi and turn them into “sushi snobs,” people well versed in “sushi lore” who will impress even Japanese sushi chefs with their authority on the subject. In his book, sushi is presented as too complex for the average Western consumer to eat without embarrassing themselves. His tone may be comedic, but the sentiment remains — sushi is a sophisticated food, and it is only for the most sophisticated of consumers.

While sushi and more traditional Japanese foods may be perceived as fare for those of higher class seeking to be more worldly and refined, not all Japanese food is consumed in the West with that attitude. Japanese snack food has experinced increased popularity in the West over the past few years, with its greatest audience being a younger generation more concerned with novelty and trendiness than class and sophistication. The consumption of Japanese snacks has seen so much growth in the West that japanesesnacks.com, a website once dedicated to the sale of Japanese snack foods, expressed pride in being “a pioneer in the Jsnack movement.” The site, which is no longer selling any product due to oversaturation of the market by copycat stores, mentions that its main customers were curious Americans. A major marketing strategy for these snacks among Western audiences is the portrayal of these foods as strange, fun, and exotic. There are several blogs, such as The Japanese Food Snack Review, that play into this perception as they focus solely on trying different Japanese snacks for the novelty of consuming something unknown and Japanese. Japanesesnacks.com also mentions regular customers being “hardcore hardcore fans of Japanese Animation, console games, and scifi entertainment.” The allure of Japanese cool thus encompasses multiple areas of consumption, as those who like anime and Japanese video games are inclined to become fans of Japanese cuisine. Jbox.comgoes so far as to sell Japanese snacks and bento on the same site as Japanese DVDs and manga.

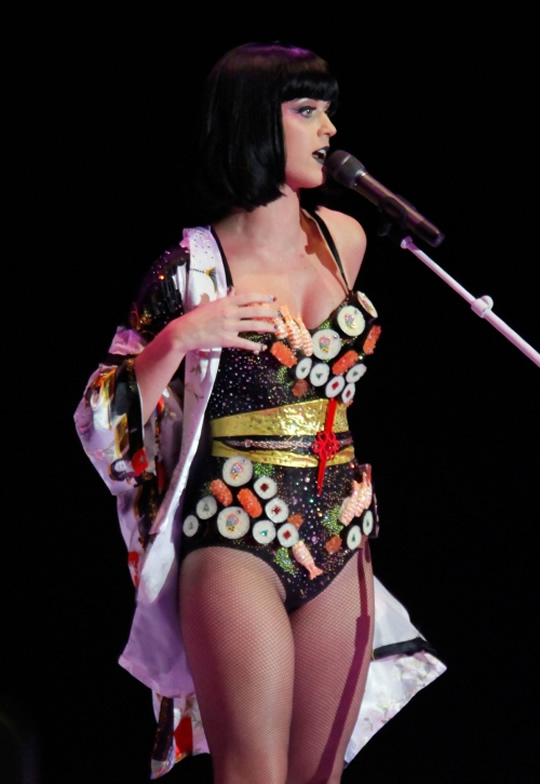

The true allure of Japanese cool in regards to food can possibly be seen best in the Western consumption of non-food items shaped like Japanese food. There is a multitude of sushi-shaped products in America – one can find sushi ties, sushi staplers, sushi pillows, sushi earrings, and sushi earbuds on many Western websites. The Japanese food craze is even visible in Hollywood, as the singer Katy Perry wore a leotard covered in sushi during her performance at the MTV Video Music Awards. Even with the culinary draw of food gone, the “Japanese cool” remains and continues to appeal to Western consumers. They are drawn to the food even when they cannot eat it.

Are there certain aspects of Japanese cuisine that make it seem more exotic and desirable to Western consumers? What ways have you seen Japanese foods marketed, and have they contributed to this Western perception of Japanese cuisine as mysterious, novel, or intriguing? Is Japanese food more reflective of Japanese culture than the cuisine of other countries?

Sources

McGray, Douglas. “Japan’s Gross National Cool.” Foreign Policy 45. Print.

Steinberg , Rafael. The Cooking of Japan. 1st ed. New York, New York: Time-Life Books, 1969. 157. Print.

Entry contributed by Katie Johannes

This was a very interesting presentation and a great entry! In particular, the discussion question “Are there certain aspects of Japanese cuisine that make it seem more exotic and desirable to Western consumers?” resonated with me – I think one could apply the same question more generally: What is it about “Japaneseness” – authentic or feigned – that seems particularly attractive to Westerners? I think the example of hibachi is a good point for discussion. Technically, hibachi is not very “authentically” Japanese, in that it was created relatively recently and was intended from its conception to cater to foreigners. Obviously, the creators of hibachi saw some sort of “need” or desire amongst their Western customers and filled it with their own ingenuity. What is the nature of that desire? Is it just a general love for the exotic, or is it something more specific? And what is it about Japanese Gross National Cool that has been so successful at filling that niche?

Another possible avenue to explore is why this Japanese cultural product – especially food – is popular with certain sub-sets of the population. Although sushi and maybe hibachi have gained an almost universal appeal outside of Japan, I have noticed in my personal experience that “Japanese Snacks” are not as widely popular, but are avidly consumed by the same sub-set of the population – young, eccentric, “nerdy” teenagers who frequently love manga and anime as well. That, at least, is my personal experience.

I think that “Japanese food” as a cultural product is not homogeneous and different products are popular with different groups for different reasons, although they all share some commonality as being part of this Gross National Cool and quasi-Orientalist Western fascination with the exotic Orient. Sushi and hibachi seem pretty universally accepted to me, while the Japanese snacks seem almost more a part of the “otaku” scene. How about other, even rarer aspects of Japanese cuisine, such as nyotaimori, which is presented in a different, less popular, more bizarre light? How is it different or similar to sushi or hibachi, or other Japanese cultural exports?

Overall, a great presentation!

This is a very interesting and engaging post. I really like you’re writing style. Very fluid, casual and effective.

I’m wondering if this review would be informed by an account of a contemporary American eating and reacting to food in Japan.

The Orientalism of the Hibachi grill fits very neatly in the paradigm we’ve worked to establish in this class thus far this semester. I’m curious to learn more about the sophistication of sushi. Why is it that sushi is seen as modern and sophisticated? When I think about it, brushed steel and modern architecture come to mind. Sophistication, without a doubt — but those are hardly orientalist or specifically Japanese signifiers. Do you see any way to connect this back to Japan, or is a diner thinking a pure America thought when he thinks of just how sophisticated he is eating his sushi? Is it just because fish is expensive and people who buy expensive things can be worldly, or is there something else going on here? I have an incling that there may be a tie-in to trendy diets to be made somewhere. Great work!