For the typical American, seeking Japanese television dramas for one’s viewing pleasures may require more effort than watching dubbed Japanese anime. Dubbed animes are regularly played during Saturday morning time slots, during late night runs on cartoon channels, and may be found on the Internet in both their dubbed and original Japanese form with subtitles. In the case of Japanese dramas, access is generally more limited—unless one has access to satellite TV (though these channels generally only carry Japanese subtitles). However, with the rise of drama-centric websites (mysoju, dramacrazy), streaming websites (Youtube, dailymotion), and the growing number of online fansub

communities (timelessubs, sars-fansubs), access to Japanese television dramas has grown in recent years. Essentially, fansubbed J-dramas, like fan-subbed anime, are not confined to American industry regulations (the FCC), unlike dubbed animes and video games. The fans download the raw, Japanese files and translate the material to the best of their abilities, explaining Japanese honorifics, puns, and celebrity references.

communities (timelessubs, sars-fansubs), access to Japanese television dramas has grown in recent years. Essentially, fansubbed J-dramas, like fan-subbed anime, are not confined to American industry regulations (the FCC), unlike dubbed animes and video games. The fans download the raw, Japanese files and translate the material to the best of their abilities, explaining Japanese honorifics, puns, and celebrity references.

Growing access to Japanese dramas (abbr. J-dramas or “doramas”) may make one feel as though one is coming closer to understanding “real Japan” –the cultural undertones of a nation different from one’s own. Though the plots of programs may not appear plausible, just as the plots and settings of American television rarely reflect actual everyday American life, there is a more plausible realism in Japanese essence in the dramas. In the case of dubbed animation, the programs are localized to cater to the chosen audience, though fan-subbed animes have since remedied the problem of localization. At the same time, though, animated series may contain the culture that the subbers wish to present to their audience, but, because of the mokokuseki, the statelessness, of animes in general, one may perceive animes as a story that happens to have undertones of Japanese culture.

Since subbed dramas’ plots and dialogues are not skewed according to other nations’ media regulations–the fansubbers present a more raw form of Japanese television culture–the gap that separates the viewers from Japan lessens. The programs are directed, written, and produced by the Japanese, characters are played and voiced by Japanese actors, and the setting is usually placed in Japan, not in a mystical parallel universe that contains undertones of Japan. It is in this sense that a viewer may feel as though he is closing in on “real Japan.” However, despite a translator’s ability to explain the concept of Japanese honorific suffixes (-chan, –san, –kun), some argue that a typical Westerner is unable to detect certain Japanese undertones.

In The Couch Potato’s Guide to Japan, author WM. Penn dedicates a chapter of his book to the sociology of Japanese TV. In this chapter, he breaks down a handful of symbolism that a regular Western viewer may not be able to detect while watching J-dramas. Penn believes Japanese dramas contain unique symbolisms that Westerners are unable to recognize and he shows this through his analysis of the presence of obentos in J-dramas.

The obento (or Japanese boxed meal) usually reinforces the state of a character’s family setting and socio-economic status, and relationship standings.

This sort of bento, prepared by the character’s mother, has, on one half, rice with a sliver of sausage placed in the center. This bento is a modern version of the hinomaru bento, or, as Penn describes it, a “plain white rice with a red pickled plum plopped in the middle” (15). The rice with the centered sausage depicts the Japanese flag. This, along with the simple side dish, indicates that the character comes from a poor but proud family.

In the drama, Hana Yori Dango, the obento is also used to represent the main character’s socio-economic background. Originally a manga and anime, Hana Yori Dango was adapted into a drama during the 2005 fall drama season, starring Inoue Mao, J-pop idol Matsumoto Jun, and Oguri Shun. Makino Tsukushi (Inoue Mao) comes from a poor family but goes to one of the most prestigious high schools in Tokyo, Eitoku Gakuen—a school full of rich kids who do whatever the F4, the four most influential guys in school, want.

In the drama, Hana Yori Dango, the obento is also used to represent the main character’s socio-economic background. Originally a manga and anime, Hana Yori Dango was adapted into a drama during the 2005 fall drama season, starring Inoue Mao, J-pop idol Matsumoto Jun, and Oguri Shun. Makino Tsukushi (Inoue Mao) comes from a poor family but goes to one of the most prestigious high schools in Tokyo, Eitoku Gakuen—a school full of rich kids who do whatever the F4, the four most influential guys in school, want.

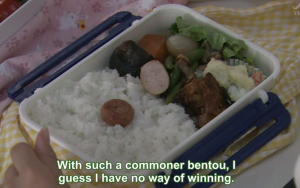

In the first episode, Makino Tsukushi’s position in the school’s social hierarchy is represented through the contents of her obento. While her schoolmates order high-class, Western dishes from the academy’s chefs, Tsukushi sits, by herself, with her obento, wrapped in its furoshiki cloth. She unties the cloth and lifts the top of the box. Beneath the lid lays an assortment of sides, and the bottom half of the box is full of rice balls, coated with rice seasoning.

According to Penn, a Japanese viewer would be able to detect Makino Tsukushi’s status based on her obento arrangement.  The fukikake seasoned rice balls, a traditional Japanese food, are in plenty, filling the lower half of the bento box. Reinforced by the appearance of the upper layer, Makino-mama, who is proud of her daughter for attending such a prestigious school, regularly packs hearty meals for her daughter. She fills every corner of the extravagant obento box (that she found in the storage closet) in order to make up for their lower class standing. Ironically, while trying to mask the family’s economic status, Makino-mama’s obento do the opposite. The foods are Japanese and lack the extravagance of the other students’ meals. Makino-mama tries to exaggerate the family’s standing by filling every corner of the box, as though to say, “Look, Tsukushi isn’t completely poor—you can’t see the bottom of her obento box!”

The fukikake seasoned rice balls, a traditional Japanese food, are in plenty, filling the lower half of the bento box. Reinforced by the appearance of the upper layer, Makino-mama, who is proud of her daughter for attending such a prestigious school, regularly packs hearty meals for her daughter. She fills every corner of the extravagant obento box (that she found in the storage closet) in order to make up for their lower class standing. Ironically, while trying to mask the family’s economic status, Makino-mama’s obento do the opposite. The foods are Japanese and lack the extravagance of the other students’ meals. Makino-mama tries to exaggerate the family’s standing by filling every corner of the box, as though to say, “Look, Tsukushi isn’t completely poor—you can’t see the bottom of her obento box!”

In her article about obento, Eva Lucks discusses the importance of this Japanese lunchbox. She calls the presence of the obento “a connection between the home (uchi) and the outside (so

to).” The obento is not just a representation of a well-fed, looked-after child—the obento also signifies the relationship between the maker and the recipient. When the recipient (usually the child or husband) journeys beyond the boundaries of home, the “outside” judges an individual based on how well-prepared, how pretty the obento are. The Japanese mentality appears to run along the vein of, the better prepared the obento is, the more likely the person will be accepted by his peers. This mentality is the motivation behind Makino-mama’s well-meaning obento.

to).” The obento is not just a representation of a well-fed, looked-after child—the obento also signifies the relationship between the maker and the recipient. When the recipient (usually the child or husband) journeys beyond the boundaries of home, the “outside” judges an individual based on how well-prepared, how pretty the obento are. The Japanese mentality appears to run along the vein of, the better prepared the obento is, the more likely the person will be accepted by his peers. This mentality is the motivation behind Makino-mama’s well-meaning obento.

However, a more readable version of the obento is its presence in indicating the standings of individuals in romantic relationships. In Nobuta wo Produce, the obento is used to depict the crumbling relationship between Kiritani Shuiji (played by J-pop idol Kamenashi Kazuya) and his sort-of-girlfriend, Uehara Mariko (played by Erika Toda). The obento becomes a more relatable part of the plot as it makes its weekly cameo, appearing during the pair’s ritual lunch dates. Uehara Mariko, in order to express her feelings for Shuiji, prepares elaborate and cutesy dishes for him, not unlike how Shuiji’s mother must have prepared his obento for him during his primary school years. Since

However, a more readable version of the obento is its presence in indicating the standings of individuals in romantic relationships. In Nobuta wo Produce, the obento is used to depict the crumbling relationship between Kiritani Shuiji (played by J-pop idol Kamenashi Kazuya) and his sort-of-girlfriend, Uehara Mariko (played by Erika Toda). The obento becomes a more relatable part of the plot as it makes its weekly cameo, appearing during the pair’s ritual lunch dates. Uehara Mariko, in order to express her feelings for Shuiji, prepares elaborate and cutesy dishes for him, not unlike how Shuiji’s mother must have prepared his obento for him during his primary school years. Since obento, as mentioned before, are an indicator of soto versus uchi, a quick, thirty-second scene represents the closeness Uehara Mariko believes the pair has. She feels close to Shuiji and wishes he would reciprocate her feelings, so she plays “house” by cooking for him—a representation of her affections.

obento, as mentioned before, are an indicator of soto versus uchi, a quick, thirty-second scene represents the closeness Uehara Mariko believes the pair has. She feels close to Shuiji and wishes he would reciprocate her feelings, so she plays “house” by cooking for him—a representation of her affections.

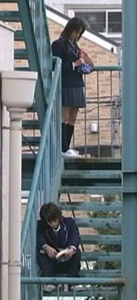

Though the western viewer is unlikely to pick up on what the  obento represents in Japanese society, the superficial indications are easily understood. After the pair break-up, Shuiji spends his lunch hour in a distant stairwell, away from his classmates, unable to reveal his new relationship status for fear that his popularity would plummet. A typical viewer may be able to pick up on Uehara Mariko’s lingering feelings for Shuiji as she continues to pack her elaborate obento, which include rice balls covered in heart-shaped seaweed. By drama’s end, Uehara Mariko only makes lunches for herself and the pair reconcile their differences and are able to part as friends.

obento represents in Japanese society, the superficial indications are easily understood. After the pair break-up, Shuiji spends his lunch hour in a distant stairwell, away from his classmates, unable to reveal his new relationship status for fear that his popularity would plummet. A typical viewer may be able to pick up on Uehara Mariko’s lingering feelings for Shuiji as she continues to pack her elaborate obento, which include rice balls covered in heart-shaped seaweed. By drama’s end, Uehara Mariko only makes lunches for herself and the pair reconcile their differences and are able to part as friends.

Other J-drama viewers have also detected symbolism of various drama plots. Blogger Hei Shing tries to unravel and make sense of running themes in another drama, Strawberry on the Shortcake. Perhaps the symbolism in Japanese television, specifically the role of the obento, is not as deep as WM. Penn perceives. As is the case of any other kind of symbolism, underlying meanings are not meaningful unless one believes them to be so. Westerns who view J-drama may miss the deeper indications of certain depicted cultural symbolism (uchi versus soto), but understand the general idea of that cultural practice (cooking as a form of affection). As Hei Shing writes, “When we watch one country’s television series, we can understand their habits, social phenomenon and favourites.” Perhaps it is in this sense that one draws closer to “real Japan”.

Discussion questions

Where do you think Japanese television dramas fall on the metaphorical ladder to “real Japan”? What is the appeal of J-dramas? Could “more Japanese” be a factor of this appeal? How real are J-dramas?

Citations

Wm Penn. “Japanese TV Sociology.” The Couch Potato’s Guide to Japan: Inside the World of Japanese TV. Hokkaido, Japan: Forest River, 2003. 14 – 18.

Leheny, David. “A Narrow Place to Cross Swords: ‘Soft Power’ and the Politics of Japanese Popular Culture in East Asia” in Beyond Japan.” Beyond Japan: The Dynamic of East Asian Regionalism. Cornell University Press: New York, 2006. 214 – 215, 229.

Entry contributed by Jessica Wang

First I want to say that I think you are right, focusing on food can grant interesting insights into culture.

I would like to leave you with the following questions, however. First – what do you mean by “Real Japan?” Does the fact that TV, dramas, movies etc are inherently presentational influence the authenticity of what you take in? For example, most US dramas about school life are hardly representative of what real people go through every day. In this sense, we can find cultural values in drama but perhaps not “reality?”

Second, unedited J-drama is analogous to unedited anime. Is your argument that because J-drama is never edited (by virtue of not appearing on US TV) that it is somehow closer to reality? What about fansubbed anime?

-Nathan-

As a fan of Japanese dramas myself, this blog post gave me further insights into the cultural background behind some of the dramas that I enjoy. I agree with you that due to the nature of live action television, certain aspects of Japanese culture may appear more prominent or be featured more distinctly in Japanese television dramas in comparison to Japanese animation. When making a Japanese anime, the budget and time constraints of the project might lead the animators to depict generic and undetailed obento and various other foods in order to spend time and money on other parts of the animation. Since real food must inevitably be prepared for any scene featuring food in a liveaction drama, the drama creators might consider it more worthwhile to pay closer attention to detail and create food that reflects character relationships for the show.

However, I would hesitate to rank different forms of Japanese entertainment based on their cultural “authenticity.” If comparing Japanese dramas to anime, why would dramas be considered closer to “Real Japan” if both forms originated from Japanese creators? Since entertainment is often fiction, how can one form of Japanese fiction be considered more authentic than another form of Japanese fiction?