What is the ‘K-Wave’?

While Japan has often been thought of as an Asian cultural superpower — with its trendy fashion, tech-savvy devices, and irresistible anime — another Asian wave of culture is steadily encroaching upon Japan’s established ‘coolness’: the Korean wave. Also called hallyu, the Korean wave is a term used to describe the tsunami of South Korean entertainment and culture that began flooding Asia starting from the 1990s, and now recently into Western parts of the world. The Korean wave includes Korean TV dramas, films, and pop music, which is known across the globe as ‘K-Pop.’ These cultural products have become staples in Asian markets formerly dominated by Japan and Hong Kong.

The Korean government has promoted hallyu, using it as a form of soft power, a term American political scientist Joseph Nye calls the ability for a country to attract rather than coerce another country as a means of persuasion. The Korean Foundation was established in 1991, a cultural tool that was formed much more recently than The Japan Foundation in 1972. In addition to the Foundation, the Korean government has also created the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, as well as the Presidential Council on National Branding, which aims to promote Korea’s global image, to right its misconceptions about Korea, its culture, products, and people, and to raise respect to support Korean business and nationals abroad.

Though the Korean government has taken extraordinary measures to encourage its students to travel abroad, this article aims to focus on K-pop and its effectiveness in the West. Korean pop music is a blend not just of Western and traditional, but of new and old. The music features catchy urban beats, easy dance moves, and lyric hooks that are often sung in English. Neither the boys’ nor girl groups’ lyrics or music videos generally refer to overt sex, drinking, or clubbing — which are usually the most popular themes in Western music. From PSY’s kooky horse gestures to Girl’s Generation’s sleek and slender legs, how exactly did the K-Wave become so big in such a small amount of time? Part of the answer lies within Japan’s globalizing methods.

J-Cool’s Globalizing Methods

K-Pop’s sudden craze in the West isn’t anything new. Koichi Iwabuchi’s Recentering Globalization capitalizes on the decentering of Western influence and the dispersion of non-Western influences that are progressively gaining more global influence — specifically Japanese ‘J-Cool’ since the burst of the bubble economy. This transnational model highlights ideas that culture is not limited to a national framework, does not flow in only one direction, and transnational cultural flows do not displace a nation’s established boundaries, thoughts, or feelings. In the case of Japan, Iwabuchi argues that Japan has little to no cultural presence in the goods it exports to other nations. Japanese products, he claims, are ‘culturally odorless’ (mukokuseki), as they do not contain many traces of Japanese cultural features within them and instead these features are erased or softened.

Iwabuchi’s theories of transculturation and odorlessness can be exemplified through Japanese music companies and the ways in which they dominated the Asian music industry. In the early 1990s, Japanese music industry aimed less to promote its Japanese musicians in the East and Southeast Asian markets; rather, the industry sought out indigenous pop stars who could then be sold to pan-Asian markets with Japanese pop production knowledge. In other words, the Japanese music industries took a back-stage role, and did not overtly promote its own Japanese artists across Asia. Instead of a Japanese band or musician, a non-Japanese artist was found and promoted across pan-Asian countries who could connect more to other Asian nations than Japan itself.

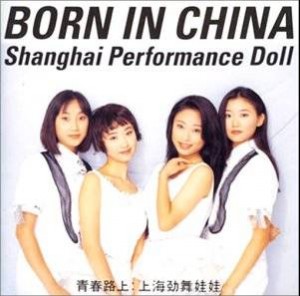

An example of this can be seen through spin-off groups of popular J-Pop groups in Japan, where the spin-off group members were non-Japanese. A group called “Shanghai Performance Doll,” for example, was a secondary group to Japan’s J-Pop girl group “Tokyo Performance Doll.” Shanghai’s mandarin-speaking group was immensely popular in China, while Japan had its own original Japanese group.

In all, Japan has established itself as a cultural superpower not only in Asia, but also in the West. Using its capital, its management know-how, and its marketing strategies, Japan had taken a dominant marketing role rather than the stage role in the music industry. By using indigenous Asians as their stars, Japan’s cultural presence seemed almost ‘odorless’ and invisible. However, while Japan sits on a formidable reserve of soft power, Korea’s music industries have built off of Japan’s methods, and have now perfected the process.

How K-Pop has Perfected Japan’s Methods

Jessica was born and raised in California, and eventually recruited to be part of Girl’s Generation.

While Japan had searched for non-Japanese stars, Korea is different in that it specifically scouts for singers of Korean origin. This, in effect, makes K-Pop far from being deemed culturally odorless. Three music agencies dominate the K-pop industry: S.M. Entertainment is the largest, followed by J.Y.P. Entertainment and Y.G. Entertainment. The agencies act as manager, agent, and promoter, controlling every aspect of an idol’s career: record sales, concerts, publishing, endorsements, and TV appearances. The agencies recruit twelve to nineteen year olds from around the world, through both open auditions and a network of scouts – though contestants who are of Korean origin and can speak Native English or Chinese are highly prized and preferred. In addition to singing and dancing, the idols study acting and three main languages: Japanese, Chinese, and English. Though on average, only one in ten trainees make it all the way to a debut.

Lee Soo-man, S.M. Entertainment’s founder, is known as K-pop’s constructor. Lee retired as the agency’s C.E.O. in 2010, but he still takes a hand in forming the trainees into idol groups, including S.M.’s newest one, EXO. The group consists of twelve boys, where six are Korean members who make up “EXO-K,” and the other six is a mixture of ethnically Chinese members or Korean boys who can speak Chinese that make up “EXO-M.” The two subgroups release songs at the same time in their respective countries and languages, and promote them simultaneously, thereby achieving “perfect localization,” as Lee calls it. An example of this can be seen in EXO-K and EXO-M’s release of their first single, ‘Mama,’ which attempts to sell the groups as boys who are gifted with supernatural abilities. In reference to promoting EXO-M, a group that is not all ethnically Korean, Lee adds:

“It may be a Chinese artist or a Chinese company, but what matters in the end is the fact that it was made by [Korea’s] cultural technology. S.M. Entertainment and I see culture as a type of technology. But cultural technology is much more exquisite and complex than information technology.” — Lee Soo-man

S.M. Entertainment and other Korean music industries draw from Japan’s technique of creating spin-off groups containing members who are not of their national origin. They establish the Japanese idea of working behind the scenes when it comes to controlling the marketing and exporting techniques of the non-Korean group. However, while the idols sing in Japanese and Chinese, the sounds, style of the music, and videos adhere to Korean principles that had made them popular in Korea.

K-Pop companies further their success through manuals. In S.M.’s case, Lee produced a manual of cultural technology, abbreviated as “C.T.,” where he catalogues the steps necessary to popularize K-pop artists in different Asian countries. The manual, which all S.M. recruiters are instructed to learn, explains the camera angles to be used in the music videos, when to bring in foreign composers, producers, and choreographers, as well as the minute specifics, such as the precise color of eye shadow a performer should wear in a particular country and the exact hand gestures he or she should make. S.M.’s stars are made and perfected into idols according to a sophisticated system of artistic development.

Thus, K-Pop has been able to tap into Japan’s globalized music efforts and perfect them. They are so perfect, in fact, that Western artists are recognizing K-Pop’s prestige, like American artist will.i.am who collaborated with Y.G. Entertainment’s English-speaking girl group 2NE1. Even Nicki Minaj is inspired by 2NE1, to the point that some of her music videos contain Korean influences.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQEabAesufg[/youtube]

K-Pop Using Anime Fan Communities As A Start?

A large quantity of Japanese soft power derives from anime and manga — and lately, K-Pop groups are starting to tap into Western fan communities of Japanese culture. One recent example of this was at Otakon 2012, one of the bigger anime conventions held on the East Coast of the US. A rising K-Pop group called VIXX (which stands for Voice, Visual, Value in Excelsis) made their first Western debut in America at the convention, with concert, autograph sessions, Q&A, and all. The group was formed much like One Direction had been on Britain’s X Factor: they were formed by the judges, and then deemed the favorite group by the audience who voted for them in a popular Korean star-search show called My Dol.

VIXX even seems to portray itself as a group that comes out of a videogame, as seen in their latest music video, ‘Rock Ur Body.’

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xG2sHvfRVOg[/youtube]

The group also has a video blog and video diary series on YouTube called VIXX TV, where fans can be updated of where the K-Pop members are, as well as see what they do on a daily life schedule. By having gorgeous faces and bodies, and by giving fans the ability to track their personal lives as a star, K-Pop groups almost seem as if they are fictional characters themselves from a pop idol anime — the only difference being that they are actually real, and in the flesh.

Who Is the Dominant Asian Cultural Superpower Now?

Though Japan has gained prestige as a cultural superpower in both Asia and the West, Korea seems to be catching up through its music industry. While Japan created a basic formula for dominating the music industry in Asia using mukokuseki, Korean pop companies have perfected Japan’s methods and have even popularized Korean music not only in Asia, but in the West as well. This brings one to speculate as to whether or not the K-Wave has the potential to take Japan’s place as the dominant Asian cultural power.

QUESTIONS

⑴ Could Korea’s effectiveness in the Western markets and in Asia be because of Japan’s ‘imperialistic’ history over Asian countries, and how Asia has harsh criticisms of Japan’s history?

⑵ Is there an overlap between K-Pop and Japanese anime/manga? Can K-Pop be seen as an easy transfer from anime/manga fans and be easier to be introduced to it? How?

⑶ K-Pop has imitated Japan’s music industry model, and has even started to tap into Japan’s fan communities of anime and manga. Can Azuma’s database model theory be applied to Korean Pop artists/singers/bands? (ex. hair styles, physique, legs, etc.) Why or why not?

⑷ Do you think it’s possible for both K-Pop and J-Cool to coexist? Or will one outdo the other in the future?

⑸ Is the J-Wave even on a decline? How so, or how is it not?

SOURCES

Bush, Richard. Public Diplomacy in Northeast Asia: A Comparative Perspective. 30 May 2012. TS. The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002. Print.

Nye, Joseph. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy 80.1 (1990): 153-171 Print.

Seabrook, John. “Factory Girls: Cultural Technology and the Making of K-pop.” The New Yorker. 8 October 2012. 25 November 2012. Web.

This was a very insightful article! Personally, I find that Azuma’s database model has definitive implications when applied to the K-Pop industry–in this particular instance, the manual of cultural technology seems an inherent aspect of this database concept. The fact that these groups are formed by popular vote on media outlets or through an audition and selection process conducted by entertainment executives only furthers this idea, as most music groups formed in the Western world do so through a common interest in a specific genre or style of music, though shows like ‘American Idol’ and ‘The Voice’ are quickly working to alter this traditionally accepted method of group formation. Assuming that a proficient use of the database model is in fact the key to an increasingly influential soft power for South Korea, this begs the obvious question of why Japan doesn’t seem to have been as successful at capitalizing on the lucrative database model which was invented in Japan itself. I wonder if the qualities of cultural odorlessness are responsible for the relatively limited success of J-Pop/Rock in the Western world, when culturally-saturated artists like PSY continue to top charts in the US and Europe.

As someone who has not knowledge of K-Pop or of the K-Wave in general, I found this article very interesting. Personally, I’ve researched the Korean population in Japan, and your articles has begged the question from me of how much the Korean population in Japan has affected the K-Wave’s success in Japan. It’s also very interesting to see an almost role-reversal between Korea and Japan. For hundreds of years, Japan was thought to be the repository and refinery of all things “good” in Asia. The fact that Korea has subverted Japan’s traditional role as this through music is very interesting, especially given how popular anime and manga is in the West. One would think that J-Pop and J-Rock would have boomed within the anime and manga fan communities, yet we see K-Pop strongly taking the reigns in that particular front. I would personally like to know your opinion on the question you posed about Korea becoming the next Asia power-culture.

Great web site you have here.. It’s hard to find high-quality writing like yours these days. Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. I really appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Karya Bintang Abadi