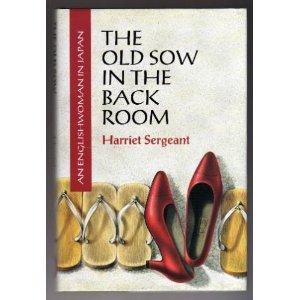

by Emily Wells

British journalist Harriet Sergeant once noted that men wrote the vast majority of the accounts of Japan. So, with husband and daughter in tow, she traveled over six-thousand miles away from home to live Tokyo for a grand total of six years. The varied assortment of characters she meets in her travels show a much broader and more well-rounded view of Japan than one would expect, but at a price. Old Sow In The Back Room paints a picture of Japan that is dismal at best, and at worst a confirmation of Western suspicions of corruption, social and gender inequality, and depression previously masked by cultural spectacle.

The main point that Sergeant tries to impress upon her audience from the start of the book to the end is the fact that one’s experience in Japan, whether you are a native or a foreigner, depends almost entirely on your gender. Western men wrote most of the well-known travelogues on Japan and most (that is to say, most that have gone for that fabled “Japanese experience”) seem utterly enchanted, and with good reason. Provided you are of some means, the men bend over backwards to make their western counterparts comfortable, the women throw themselves at them, and women are hired for the sole purpose of being pretty and delightful. Sergeant, however, saw no ceremony, no indulgence, no proverbial “slack”. She was on her own, left to her own devices with nothing more than a few weeks of Japanese lessons.

In her travels, she joins the social circle of Mrs. Abe, with whom she first learns about etiquette and gender norms. She goes on to befriend Yuno, a professional gambler and member of the yakuza, and Midori, a young woman who ignores her country’s expectations of what women should do but finds herself without a side she can identify with. The elderly of the Kobokan Community Center teach her about the Great Kanto Earthquake and see themselves as living relics of a very different Japan long since dead. A visit to a family of burakumin, the Japanese equivalent of India’s untouchables, further drives home the severity of Japanese ideas of social hierarchy. They are far more warm and affable than most higher-class Japanese that Sergeant meets, with a sense of family unity that seems to come from facing generations of contempt..

While Sergeant’s tale is first and foremost an account of her travels and personal experiences in Japan, it is without a doubt a comparison and criticism of the country in how it conflicts with western ideas. Her visits to Mrs. Abe and her many attempts to navigate and follow the rules of a strange city give the impression that Japan is simply rigid and fixated on etiquette, which one may not be keen on but would surely agree is not worthy of condemnation.

Sergeant never explicitly criticizes Japan, but simply retelling her experiences and feelings at the time evoke enough empathy from a western reader to remove any need for blatant criticism. It is in her unique perspective as a woman and a mother that the reader gains a true understanding of what goes on behind the scenes. Women fill minor roles in society and are expected to marry before they are considered past their prime and forever afterward are only wives and mothers who are to sacrifice everything for their parents, in-laws, husband, and children. Japan is known for placing heavy pressure on students and salary men, but that which is placed on women is rarely acknowledged. And though Sergeant is clearly concerned by the near-total divergence of spouses and the coldness she perceives between them, she spends most of her time on her own, away from her husband and with her child in the care of a nanny (which is an exotic and somewhat appalling luxury to Japanese women.)

The most telling episodes in the entire book, however, deal with the infamous yakuza. The first glimpse is with Yuno, who shows her a not-so-underground family reminiscent of The Godfather and its prevalence in government and business. Several smaller incidents show shop home owners threatened and forced to pay protection money and yet think it’s just how things are done. While the yakuza are portrayed mostly as a sinister, unseen force, they are given a moment of sympathy when Sergeant discovers that, being primarily made up of the ostracized burakumin, they are a product of the system they manipulate.

Every anecdote and chapter in her book is essential, however minor or trivial it may initially appear. Learning new words shows how ingrained certain concepts are into the Japanese psyche, a trip to a public pool shows the parental role of the government, and a preschool questionnaire shows the excessive involvement Japanese mother have with their children. No part of this book could or should be cut down or paraphrased. I was unaware that Sergeant spent six years abroad before reading the inside cover because the book was so engrossing that it never seemed tedious in the least. That, in combination with a commentary free of prejudice and Sergeant’s wide range of acquaintances and daily experiences is what makes Old Sow In The Back Room such a revealing portrait of Japan. Through a woman’s eyes, she manages to peel back the superficial layer that the West sees, like peeling back the drywall to see what’s living in the walls.