“I wanted to compose real surrealistic music in a non-musical way. Surrealism is also reaching unconsciousness. Noise is the primitive and collective consciousness of music. My composition is automatism, not improvisation.”

“Pornography is the unconsciousness of sex. Noise is the unconsciousness of music. Merzbow is erotic like a car crash can be related to genital intercourse. The sound of Merzbow is like Orgone energy– the color of shiny silver. ”

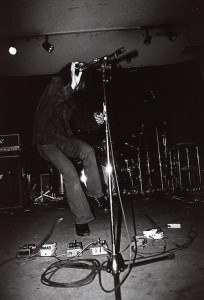

Masami Akita, AKA Merzbow [1]

As is the case with any musical genre, the historicizing of the influences and origins of noise comes to be an exercise in retroactive mythmaking. Some trace Japanoise to the experimentations of British industrial groups such as Throbbing Gristle, others to the more academic works of composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen. Masami Akita however, known to the world as Merzbow, one of the most influential and enduring Japanese noise artists, states that he simply had no musical influences whatsoever, instead drawing a line between himself and the Surrealists and Dadaists of the art world, taking his stage name from Karl Schwitters’ “Psychological Collage” architecture piece the Merzbau. In any case, a number of Japanese noise artists appeared in the early 1980s who differentiated themselves from any comparable musical movements from the past with an unwavering devotion to producing pure, unadulterated noise, free from any ideological restraint or traditionally “musical” ideas. As Merzbow explains, “Industrial music used ‘noise’ as a kind of technique. Western Noise is often too conceptual and academic. Japanese Noise relishes the ecstasy of sound itself.”[1]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbBBczzDeCA[/youtube]

In Merzbow’s early recordings, he sought to create music free of the human body, free of instruments, starting with pre-existing sound on tapes which he would simply distort and edit. Other groups such as Incapacitants showed a similar attitude, insisting that their performances not only were free of any human intention or ideology, but in fact had nothing to do with music (a claim many of their listeners found easy to agree with.) Band slogans such as “I hate art I love noise” (Masonna), “Art is over” (The Gerogerigegege) and “No Meaning, No Message, No Image” (Incapacitants) insisted on these points with a dogmatism bordering on the more ideological Western noise musicians from which they wanted to distinguish themselves. Some of these groups released no studio recordings throughout their whole career, and those that did usually only later. Merzbow describes how he also made a shift from his early tape experimentations to live analogue performances: “My first motivation for creating sound was anti-use of electric equipment- Broken tape recorders, broken guitar, amp etc. I thought I could get a secret voice from equipment itself when I lost control. That sound is unconsciousness, libido of equipment. Then I tried to control them with more powerful process.” [2]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3kworqbeqw[/youtube]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKuZzR2FknI[/youtube]

However, beginning in 2000, Merzbow began making all of his music on a computer. Throughout the 80s and 90s, his shows would involve dozens of pieces of equipment, but now include only two laptops and a mixer. Contrasting the automaton creation he championed in the past, he now usually plays prerecorded samples while sitting behind his laptop, the music sometimes even incorporating something that would resemble a traditional beat, which would have been unthinkable for noise music in the past. While some of the more classic Japanoise acts such as Masonna and Hijokaidan still keep up with their wildly violent analogue performances, most of the newer noise artists have switched to totally digital creations often incorporating samples.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNjEwCesULo[/youtube]

Speaking of this kind of production, Merzbow says “nothing is really destroyed or disappears, as recycling is part of production. It’s a natural and necessary part of post-capitalism. There should be no illusion of only production, as was the case with early industrialization. We no longer use a dialectical approach in our disposal/recycling system, only a forward movement to the reproduction of reproduction.” [3] He himself certainly exemplifies this forward movement, having produced well over 300 albums of music despite having released virtually nothing in his first decade as an artist. This new image of noise that Merzbow has helped to create, mechanistically hyper-recycling, has moved the image of the scene away from the violent exhibitionism of the 90s into something arguably completely unique in the music world: the ultimate commodity, the gesture of “music” without the substance, existing in a dimensionless, referentless world of undifferentiated noise consumed indiscriminately by consumers downloading from across the world, rather than by devoted fans in an intimate live setting.

On the subject of the similar death of the analogue in digital photography, Jean Baudrillard writes, “In this digital liberation of the photographic act, in this impersonal process in which the medium itself generates mass-produced images, with no other intercession but the technical, we can see seriality in its consummate form… For this is really the last straw, this aspiration to clear the way, with the digital, for the integral image, free from any real-world constraints. And we would not be forcing the analogy if we extended this same revolution to human beings in general, free now, thanks to this digital intelligence, to operate within an integral individuality, free from all history and subjective constraints… if subjective irony disappears– and it disappears in the play of the digital– then irony becomes objective. Or it becomes silence.” [4] Baudrillard is referencing specifically how the digital manipulation of photography ends the play of absence and presence seen in the image between which an analogue divides reality and illusion. He claims that such a duality is the basis of subjectivity, irony, and reality, and that in our world consciousness has ceased to exist because there is no reality against which to struggle, irony has ceased to exist because there can be no tension between intent and reality. Everything, including machines, are saturated in subjectivity to the point that subjectivity has ceased. These kind of arguments lend themselves well the the act of producing digital noise. Music that is already cut up and devoid of any sensibility of craft or entertainment value, it is a narcissistic reflection of the listener’s experience, found in the impersonal process of the machine. Like pop music, it offers no catharsis, takes part in no narrative aside from that of the instantly gratifying commodity. No progress, no emotion, no humanity.

“Sometimes, I would like to kill the much too noisy Japanese by my own Noise. The effects of Japanese culture are too much noise everywhere. I want to make silence by my Noise.”

– Merzbow [1]

Questions:

Does Japanoise seem to you closer to the academic avant-garde or something like hardcore punk, or somewhere in-between? If you watched some of the above noise performances, how do you think they relate to the tradition of rock n’ roll performance? Destructiveness and excess seem to have always been a part of that tradition, but The Sex Pistols at least played some instruments. Does the subtraction of the pretense of musical creativity herald something new in this respect, or is it just more of the same ineffectual, juvenile rebellion displaced into the culture industry? Or would you in fact place (digital) noise as something more akin to pop music, both caught in machine-like automation?

Do these images fit into the images of Japan we have discussed in the course thus far, whether by similarity or contrast? The website for PSF Records, a label specializing in a lot of Japanese noise, reads “SHATTERING THE MYTH OF JAPANESE CONFORMITY” on its homepage. What do you make of this?

Sources:

- http://www.esoterra.org/merzbow.htm

- http://noiseweb.com/merzbow/all.html

- Liner notes. Rainbow Electronics. CD. Alchemy Records, 1990.

- Baudrillard, Jean. Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2007.

As much Japanese music as I have listened to in the past, this genre is completely new to me. While I can’t say that I particularly enjoyed what I heard, it seems to me that Japanoise isn’t really marked as being from Japan, but rather acultural or even postcultural. Considering the fact that this style has no message or meaning, can it be associated with anything at all, in fact?

Japanoise seems to parallel the punk, grunge, metal, and other “deviant” musical genres in that it diverts from the norm, often to extreme. This is also seen to some degree in Visual Kei especially with the more “out there” groups such as Dir en Grey. I have to wonder what it is about Japanese musical groups that take it to this degree, however. No band of any other nationality that I’ve ever heard has been quite as… odd on such a popular level.

Overall a great post. I really felt like I learned something.