by Arielle Kahn

In the past forty years, sushi has taken America by storm. Beginning as an obscure immigrant import thought to be unpalatable due to its tradition of using raw fish, sushi has since exploded in popularity, becoming an American symbol of sophistication, health-consciousness, and trendiness. It has been estimated that between 1988 and 1998, the number of sushi bars in the U.S. quintupled (Isle, 2005). Sushi is now a ubiquitous commodity, available not only in high-end restaurants or sushi bars, but also as fast food, prepackaged at the grocery store or on college campuses. Even non-edible representations are popping up everywhere, in the form of accessories, clothes, and knick knacks, from earrings to purses to refrigerator magnets to shower curtains. In America, sushi has firmly established itself as “cool.” Why did this happen?

Sushi, like many other aspects of Japanese culture, came into the public eye in the 1970’s, during the rise of Japan as a global economic power. At this time, many Japanese chefs were coming to America, making Japanese cuisine more available to Japanese expatriate businessmen and their American colleagues. The increasing visibility of Japan and Japanese culture, combined with the spreading availability of sushi nationwide hooked some and interested many. Soon, celebrities and other high-profile personalities were declaring their love for sushi, while the rising culture of young, urban, health-conscious adults extolled sushi’s low-fat and high nutritional virtues. Thus, eating sushi became fashionable and cosmopolitan. Because it is sometimes perceived that the diner must have a refined palate to appreciate raw seafood, or that one must behave in certain ways to eat sushi “correctly,” the ability to appreciate “authentic” sushi correctly has become a status symbol among many Americans (Allen and Sakamoto, 2011).

However, as might be expected, sushi in America has been significantly altered from its Japanese roots. American sushi avoids some of the more exotic ingredients found in Japan and has added a few of its own local ingredients, including avocado, soft-shell crab, cucumber, and even cream cheese. Differing tastes among Americans have produced many new varieties of sushi. In fact, many American favorites are barely Japanese in origin at all, but have instead been invented in the States. Such standards as California rolls, Caterpillar rolls, Dragon Rolls, and Rainbow rolls are all classic U.S. choices that were invented in America to market to Americans. Not only are these rolls an American innovation, but rolled sushi known as maki, which Westerners are most familiar with, is itself an uncommon style of sushi in Japan. There, the most commonly eaten sushi is the simple nigiri style, which is composed simply of a ball of sushi rice topped with a sliver of raw fish. In America, the uramaki style, or “inside out roll,” with the rice on the outside and nori (seaweed) on the inside, became the most popular. Additionally, American sushi tends to be more complex, with many ingredients combined to make one roll, sometimes accompanied by sauces and elaborate garnishes (Allen and Sakamoto, 2011).

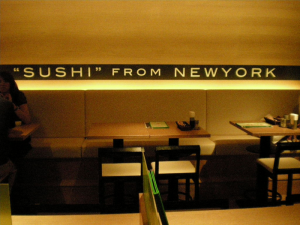

The most curious thing about the global sushi phenomenon is that sushi has now been altered to such an extent in America that it is actually being imported back into Japan in the form of “American-style” sushi. There are now many restaurants established in Tokyo which exclusively serve “American” sushi, and they cater to Japanese rather than to expatriate Americans (Allen and Sakamoto, 2011). This style tends to emphasize maki sushi, using a wide array of other ingredients apart from raw fish, making this form of sushi at once familiar in concept and exotic in style to its Japanese consumers. Like sushi in America, American sushi in Japan is marketed to young, urban professionals as trendy, sophisticated, modern, and healthy, whereas traditional Japanese sushi is not particularly associated with any of those attributes. Unlike sushi in America, which is supposed to be low in fat and therefore eschews meat, American-style sushi in Japan includes meat ingredients, which are not traditionally used in sushi, but which carry a sense of American-ness to Japanese consumers. Menus at these restaurants emphasize the Western influence by often containing English names written in romanji, Roman characters, with descriptions below in Japanese. Often, the sushi is prepared in the kitchen, out of sight, as opposed to being prepared right before the customers’ eyes at the sushi bar, as would be the custom in a traditional Japanese sushiya (Allen and Sakamoto, 2011). All of these characteristics add to the image of American-style sushi as a foreign food. What was once an iconic and ordinary Japanese snack food was exported, transformed, and is now returning to Japan with a foreign twist, as something new and original, to be consumed in a new way with a different attitude.

This phenomenon illustrates the highly unusual cultural interplay between America and Japan. This is neither a case of Japanese culture infiltrating American tastes and preferences, as with the rise in popularity of anime and manga, or of America ingraining itself in Japanese society, as McDonalds and Hollywood have done, but rather a double exchange, a hybridization. Sushi in America is a fusion of Japanese and American cuisine, and American sushi in Japan is a fusion of that fusion. Clearly there is a mutual regard for and excitement about the novel, trendy qualities of the other’s culture and cuisine. American sushi in Japan is unique in that it captures and integrates together the dueling Japanese sense of national pride and identity with the desire for novel, foreign, and especially American items. Perhaps this phenomenon is among the first drops in a wave of global cultural hybridization to come.

Discussion questions:

1) What is it about an American version of a traditional Japanese dish that Japanese find appealing? Allen and Sakamoto suggest that, because it is perceived as new and different, that “American sushi’s consumption in Japan can be understood, therefore, as a kind of playful fetish,” akin to those for school girls, blonde boy bands, butler cafes, and cuteness. What do you think about this idea? What are some other possible reasons for the popularity of American sushi in Japan?

2) When something is treated as Japanese in America, and as American in Japan, where does it come from and how can it be defined? How can we understand the origin of this kind of culture? What are the implications of this seeming lack of cultural boundaries?

3) Allen and Sakamoto write that “[Japanese] consumers eat [American sushi] with curiosity, playfulness, and at times even with irony, conscious that they are consuming others’ perceptions of something they are familiar with in its “authentic” Japanese form.” Does this observation support Iwabuchi’s suggestions that Japanese engage in self-Orientalism by believing their culture to be impossible for a non-Japanese to understand, and perhaps finding amusement in the misconceptions that foreigners have of Japanese?

Sources:

Allen, Matthew and Sakamoto, Rumi, Sushi Reverses Course: Consuming American Sushi in Tokyo, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 5 No 2, January 31, 2011.

http://japanfocus.org/-Mathew-Allen/3481

Iwabuchi, Koichi, Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Nationalism. Duke University Press, 2002

Ray Isle, Sushi in America http://www.foodandwine.com/articles/sushi-in-america

This was a fascinating read; great job, Arielle! I had no idea that “American” sushi was so popular in Japan. I’m not sure I agree with Allen’s argument that this popularity is based on some sort of fetish, nor do I believe that cultural irony is the primary motivator here, although it probably does play a limited role. Rather, I think this amalgam of a Japanese traditional dish and American food products is apparently being treated as an almost completely new and different food by native Japanese. The fact that American sushi is treated as hip, fashionable, and healthy in Japan, unlike its more traditional counterpart, would seem to support this.

I think in order to better understand why this phenomenon occurred, it would be helpful to look at demographics. What kind of people are the primary consumers of American sushi in Japan? Is there any correlation between this sushi and a particular age group, gender, or social class? Are there any specific subcultures to take into account here? For example, is there some Japanese equivalent of the American hipster subculture that would lend credence to Allen’s theory about irony being a major factor? Again, great post, and I look forward to discussing this article in further detail in class!

Great post! I think something that could add to your points would be citing some differing advertisements for American-style and more traditional style sushi in Japan. I think Allen’s claims about the ironic and playful aspects of American sushi in Japan are very interesting, but it’s hard to know how to feel about them when encountered on their own. Advertising is of course one of the principle ways “myths” are made, how meaning is generated from products, so it would be really cool to see what kind of narratives the Japanese themselves spin around these two contrasting kinds of sushi.

I like your point that the global status of sushi is not the same as that of neither anime nor McDonald’s, and I think you could develop in a bit more. Would you qualify sushi as mukokuseki? And if so, how does this relate to its potential role in self-Orientalization?