by Dylan Reilly

Imagine, that, for whatever reason, life seems simply unbearable to you. You may be in school and being constantly bullied, or having a job you hate with no foreseeable hope for a better one, or you may simply be depressed. Now think, what kind of solution is there for you? In Japan, one of the most common answers for young people seems to be “stay home and don’t come out”.  An increasingly prevalent issue in modern Japan, and especially its youth, is that of the hikikomori. Literally meaning something like “being confined”, it refers to the shut-in population of the country. However, this does not refer to those who must remain in their homes because of extenuating circumstances like health, but rather fully healthy (usually) individuals who simply refuse to leave their house, and often not even their room at that. Some may occasionally leave for such things as short shopping trips or meals with their family. [1] And interestingly enough, around 80 percent of hikikomori are male. [2]

An increasingly prevalent issue in modern Japan, and especially its youth, is that of the hikikomori. Literally meaning something like “being confined”, it refers to the shut-in population of the country. However, this does not refer to those who must remain in their homes because of extenuating circumstances like health, but rather fully healthy (usually) individuals who simply refuse to leave their house, and often not even their room at that. Some may occasionally leave for such things as short shopping trips or meals with their family. [1] And interestingly enough, around 80 percent of hikikomori are male. [2]

It is also important to note that the development of the hikikomori as a social phenomenon is a relatively recent one; its first inklings began to appear around the mid-80’s. [1] One of the factors attributed as a spark to the proverbial flame is Japan’s lackluster economy; many young Japanese, not just hikikomori, are without jobs, or part-time ones at the most. And thanks to this, an overall feeling of depression or helplessness so characteristic of the “hikki” mindset has begun to emerge. However, at the same time, it is common for many Japanese youth to live with their parents anyway, and because of the disposable income this older generation has despite economic trouble, the option of staying home becomes more and more appealing. It only gets better when one learns that parents of hikikomori often do financially support their children into adulthood. [1]

However, these “hikki” are not returning to their houses simply because they are lazy, as easy as it would be to label them that way. Instead, it appears more likely that this seclusion is a very Japanese response to the messages that permeate Japanese society. Contrary to the messages seen in the West that promote independence and action from an early age, Japan takes pride in obedience, conformity, and discipline. As a result, instead of the loud, rebellious “punks” one sees in Western culture, it is believed by some that hikikomori have the same intentions or feelings of “not fitting in”, and that society has led them to “rebel” by shrinking away. [2] As spoken by the mother of a hikikomori, “a person who challenges, or makes a mistake, or thinks for himself, either leaves Japan or becomes a hikikomori.” [2] These people may find fault with Japanese society or feel stifled by it, but because of its nature, there is nowhere for them to go but in. Some propose that the Japanese tendency to see solitude as something noble helps the hikki cause as well.

Now, there seems to be something very odd about all this (aside from the obvious). How do these people manage to survive? Or, to be more specific, why do the parents of these shut-ins continue to feed and/or at least provide a home for their children? It seems difficult to understand here; it seems more common for people to kick out a lazy twenty-something, or to help them find a job if the problem is not as serious. But it seems to come down, once again, to some of the ideas of Japanese culture. Used to already providing for their children, as so many Japanese parents do, some simply become used to the idea of continuing to do so. Others follow the mantra of not sticking out or rocking the boat, and so attempt to keep “business as usual” within the home. Sadatsugu Kudo, the head of Youth Support Center, one of many hikikomori “rehabilitation groups”, explains that “Most parents feel that hikikomori is a failure of their child-rearing.” [1] However, some parents genuinely fear that their child will no longer be able to function in the real world, and that the only way for them to survive is to be supported by these parents [1].

The emergence of the hikikomori holds a unique space within the borders of National Cool; while it is a known phenomenon within it, and has garnered a good deal of attention, it represents one of the harsher realities of Japan. It is studied about by those captured by its flashier exterior but in the end its negative qualities are often glossed over or worse, idealized into a “way of life” rather than a serious problem. Will this trend only grow as time goes on, or will something change to halt its growth? And even if something does change, will one thing be enough, or will these people remain almost literally and hopelessly encapsulated, while the rest of Japan flows on ahead?

Discussion:

Some believe that the existence of the hikikomori represents a uniquely Japanese social disorder. Do you agree with this thought, or is it possible to find people living similar lifestyles for similar reasons around the world?

If one of the purported reasons for hikikomori is the current ideal of Japanese society, do you think their numbers will rise in the future?

An odd note is that 80 percent of hikikomori are male. Why do you think male hikikomori are more prevalent than female ones? In addition, do you think there are unique factors that influence these few female hikki?

Sources:

1. Jones, Maggie. “Shutting Themselves In.” The New York Times. 15 Jan 2006. Web. 26 Mar 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/15/magazine/15japanese.html?pagewanted=1&_r=2

2. Zielenziger, Michael. “Retreating Youth Become Japan’s ‘Lost Generation’.” Excerpt from Shutting Out the Sun. NPR. 24 Nov. 2006. Web. 26 Mar 2011. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6535284

3. Gallagher, Paul. “Hikikomori – The Silent Sufferers.” Dangerous Minds. 14 Nov. 2010. Web. 26 Mar 2011. http://www.dangerousminds.net/comments/hikikomori_the_silent_sufferers/

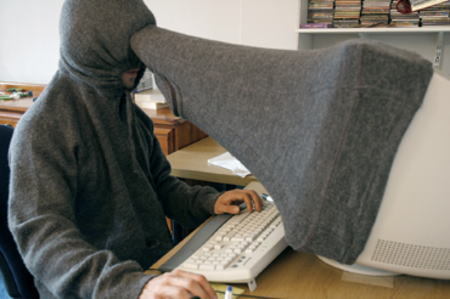

Wow, what a fascinating, engaging article. I love your style and tone. It really works for a blog-style post. I had no idea the hikikomori existed. I like that you say that “seclusion is a very Japanese response” and then back it up with good information. I want to see some more information on what exactly the hikikomori do, how do they feel, their perspectives on why they are a hikki… a little profile or snapshot into their day. Plus, a caption for the sweatshirt/computer contraption. Do they need to be in darkness? Why does this thing exist? I also think it’s interesting that the majority of hikki are male, however I would not be able to answer that discussion question confidently with the information presented in the article, because I know nothing about the topic. I think giving an average profile of a shut-in type or some average facts and figures would be the most useful thing to bulk up your post 🙂

Dylan, this is an interesting topic indeed. I wasn’t sure about your statement that this phenomenon was due to the “nail that sticks out gets hammered” thing, because it doesn’t seem to be a normal thing, and I don’t think parents feeling their parents was a failure is normal either! At least I would hope not. The main thing I was wondering though was how this compared to other countries, which I think would clarify the Japanese cultural values involved in the phenomenon. Of course, in the U.S. we have the phenomenon of basement-dwellers, which are not at all a huge part of the population, but seem to be very similar to this. In fact, I have been reading recently about people notificing a general trend of delayed adolescence in the U.S., namely, young college grads just sort of bumming around not following the preordained career/marriage/family path. This phenomenon has also been on the rise in Europe, due to higher levels of unemployment. Especially in Italy, it is becoming more and more common for young adults to stay with their families, though this seems to be more practical reasons, and more females participate as well. I’m not sure if you want to go in that direction, but I feel that it could provide an interesting perspective and make the overall argument more relatable to Western readers. I Googled “young adults staying at home unemployment italy” and found a ton of documents related to the topic so maybe it that would help. You could also discuss whether these phenomenons are a case of parallel development or whether it’s a general trend that has developed in young adults around the world… Anyhow, those are just some thoughts. Hope that helps!