An Epidemic of Gender-Based Violence in Papua New Guinea

Written by Bianca Curtin

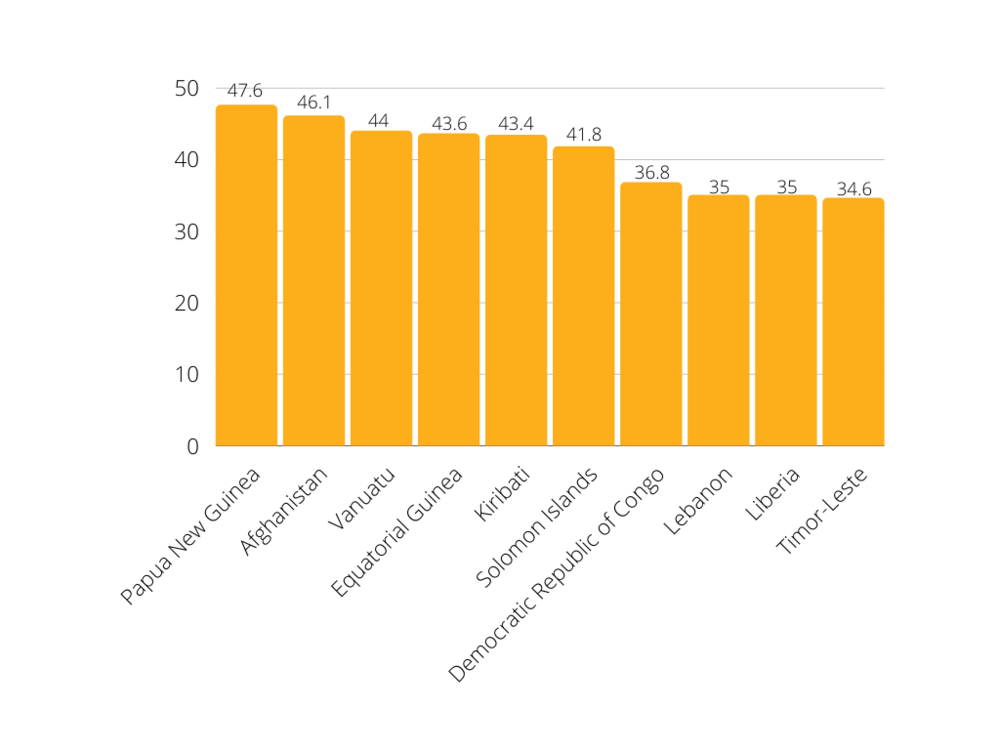

There is an epidemic sweeping the nation of Papua New Guinea (PNG) — and it’s not COVID-19. Gender-based violence (GBV) has rapidly been on the rise in PNG across the past few decades, now reaching proportions wherein the nation is among the world’s most dangerous places to exist as a woman or girl.

The statistics speak for themselves: in Papua New Guinea…

- A woman is beaten every thirty seconds

- Over 1.5 million experience GBV annually

- Forty-one percent of men admit to having committed rape

- More than two-thirds of women and girls between ages fifteen and forty-nine suffer physical and/or sexual violence at some point in their lifetime — nearly twice that of the global average

Whatsmore, data analysts suggest that GBV is likely under-reported in the region, given that the overwhelming majority of survivors who seek assistance do so through informal channels, predominantly in familial and village networks.

This past May, a three-day parliamentary inquiry was conducted to investigate the status of gender-based violence in PNG, which was said to have become more rampant following the COVID-19 pandemic. It found that the nation was severely lacking in terms of resources and policy coordination combative of GBV, especially once compared to the staggering quantity of such cases. In 2020 alone, about 15,500 domestic violence cases were reported — yet merely 250 individuals were prosecuted, less than half of whom were ever convicted.

The inquiry’s committee members thus compiled and issued a seventy-one item list of recommendations to the parliament of Papua New Guinea, including suggestions to increase funding for counseling services, implement widespread reproductive health services, and follow through with the federal action plan to counter alleged sorcery-related violence. They also convened with international development partners so as to establish partnerships against GBV.

(Source: United Nations)

In September, the prime minister of Papua New Guinea, James Marape, claimed that his administration was moving towards implementation of the reports recommendations — however, any federal records or plans pertaining to this has yet to be revealed.

The history of colonization in Papua New Guinea is one ripe with eurocentrism and western-based ethnocentrism, as has typically been true of colonial efforts in foreign nations. This history substantially took root in the nineteenth century, as Dutch colonists conducted trade throughout the Pacific archipelago. Slave trade was particularly prominent during this time, with over 20,000 indigenous peoples forcibly transported to locations such as Fiji and Australia’s Queensland through the year 1884. In 1889, Germany and Great Britain settled to annex the region between them, the former acquiring New Guinea as a colony and the latter declaring Papua a British Protectorate. Britain would go on to transfer rule of the territory to the newly federated nation of Australia in 1906, who would later invade German New Guinea amidst the events of World War I. It was not until 1945 that the nation assumed total control of both regions, and another four years before they united, thus becoming what we now know as Papua New Guinea. Australia’s administrative activity in the territories was, however, impaired by their systemic eurocentrism. Their ignorance in terms of the distinct cultural, natural, and socio-structural fortitude of both New Guinea and Papua produced little to no economic development.

The history of colonization in Papua New Guinea is one ripe with eurocentrism and western-based ethnocentrism, as has typically been true of colonial efforts in foreign nations. This history substantially took root in the nineteenth century, as Dutch colonists conducted trade throughout the Pacific archipelago. Slave trade was particularly prominent during this time, with over 20,000 indigenous peoples forcibly transported to locations such as Fiji and Australia’s Queensland through the year 1884. In 1889, Germany and Great Britain settled to annex the region between them, the former acquiring New Guinea as a colony and the latter declaring Papua a British Protectorate. Britain would go on to transfer rule of the territory to the newly federated nation of Australia in 1906, who would later invade German New Guinea amidst the events of World War I. It was not until 1945 that the nation assumed total control of both regions, and another four years before they united, thus becoming what we now know as Papua New Guinea. Australia’s administrative activity in the territories was, however, impaired by their systemic eurocentrism. Their ignorance in terms of the distinct cultural, natural, and socio-structural fortitude of both New Guinea and Papua produced little to no economic development. Papuans began to demand independence in the wake of World War II, though the might of this movement was weakened by the PNGs century-long political and economic stagnation under euro-colonial rule. With a population wherein the majority was illiterate and most citizens engaged in low income occupations, nominally subsistence farming, Papuans from all over experienced little to no interaction with public officials, or government in general. Thus, feelings of nationhood and ethnocentrism were scarcely prominent, thereby mitigating the strength of pro-independence advocacy. Nonetheless, such efforts gained significant traction in the early 1970s following a sharp rise in unemployment and subsequent mass riots, self governance finally being accomplished in 1973. Papua New Guinea’s first prime minister, Sir Michael Somare, would establish the nation’s first independent government shortly thereafter in 1975 — this enormous shift fostering the beginnings of ethnocentrism among Papuans for years to come.

Papuans began to demand independence in the wake of World War II, though the might of this movement was weakened by the PNGs century-long political and economic stagnation under euro-colonial rule. With a population wherein the majority was illiterate and most citizens engaged in low income occupations, nominally subsistence farming, Papuans from all over experienced little to no interaction with public officials, or government in general. Thus, feelings of nationhood and ethnocentrism were scarcely prominent, thereby mitigating the strength of pro-independence advocacy. Nonetheless, such efforts gained significant traction in the early 1970s following a sharp rise in unemployment and subsequent mass riots, self governance finally being accomplished in 1973. Papua New Guinea’s first prime minister, Sir Michael Somare, would establish the nation’s first independent government shortly thereafter in 1975 — this enormous shift fostering the beginnings of ethnocentrism among Papuans for years to come.