Phenological Timing and Abundance

During the study period, we were able to measure variables for seven focal species, specifically five forbes and two grasses. The relevant forbes were Sidalcea malviflora, Plectritis congesta, Plagiobothrys nothofulvus, Achyrachaena mollis, and Collinsia grandiflora, and the relevant grasses were Festuca roemeri and Danthonia californica. We found significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test p<0.05) across data collection weeks in three species: Plectritis Congesta, Sidalcea malviflora, and Festuca Roemeri. Phenology advanced in warming treatments for the forbes P. congesta and S. malviflora. F. Roemeri was found to have higher spikelet abundance in drought and control treatments, but no significant change to phenology.

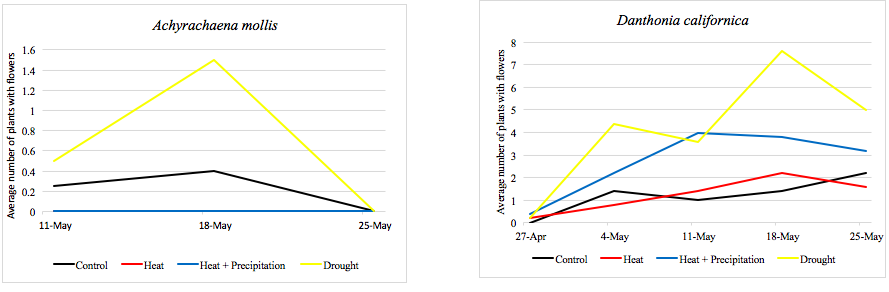

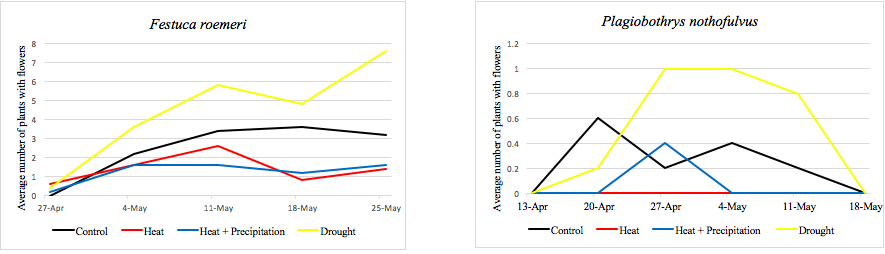

Earlier flowering times were predicted for all species in response to warming in both heat and heat plus precipitation treatments, but only two species, P. congesta and S. malviflora, had significantly earlier flowering times (Fig. 3). Both of these species were already flowering on the first day of data collection (Fig. 2). However, drought conditions appeared to advance phenology as quickly or more quickly than any other treatment for every other focal species (Fig. 1). First flowering occurred in four of the focal species for both heat and heat plus precipitation treatments, with only three observed in control (Fig. 1). Yet drought had the highest, with the first flowering of six species observed within respective plots (Fig. 1).

F. roemeri generally proved much more plentiful within drought and control treatments than within heat and heat plus precipitation treatments, as well as more reproductive (Fig. 3). Drought treatments produced the most plants with spikelets on average, while heat treatments generally produced the least for F. roemeri (Fig. 3). While drought conditions don’t appear to be a threat to the fitness of this species, warming conditions do appear to alter abundance.

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

NDVI was analyzed by treatment for each day using ANOVA and Tukey’s test. NDVI had no statistically significant differences across treatments, apart from May 25, when there were marginally significant differences between drought and both heat and heat plus precipitation treatments. As for any observable trend, the index appeared fairly the same for drought and control (Fig. 4). In addition, heat seemed analogous to heat and precipitation, apart from relatively large rises and falls in heated plots date to date in the latter half of the data collection period (Fig. 4). Data for April 27 was excluded due to entry error.

[embeddoc url=”https://blogs.uoregon.edu/phenology/files/2018/05/ELP-Final-Report-2018-1-1vdwkot.pdf” download=”all” viewer=”google” ]