Oregon Leading the Nation in Clearing Backlog of Untested Rape Kits with Survivor-Focused Legislature

Oregon is one of three states that has cleared its backlog of untested rape kits and isn’t stopping there. Oregon’s state legislature requires a survivor focused approach to keep the backlog gone for good.

By Ruben Estrada, Hannah Kanik and Ariana Sinclair

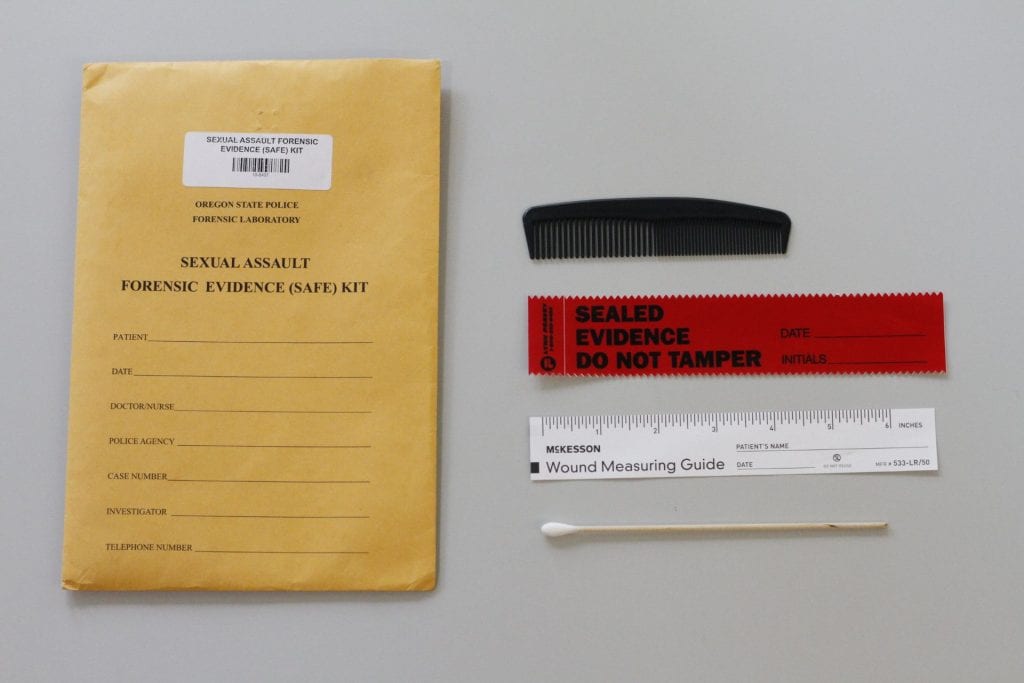

- The components of a Sexual Assault Forensic Evidence (SAFE) kit.

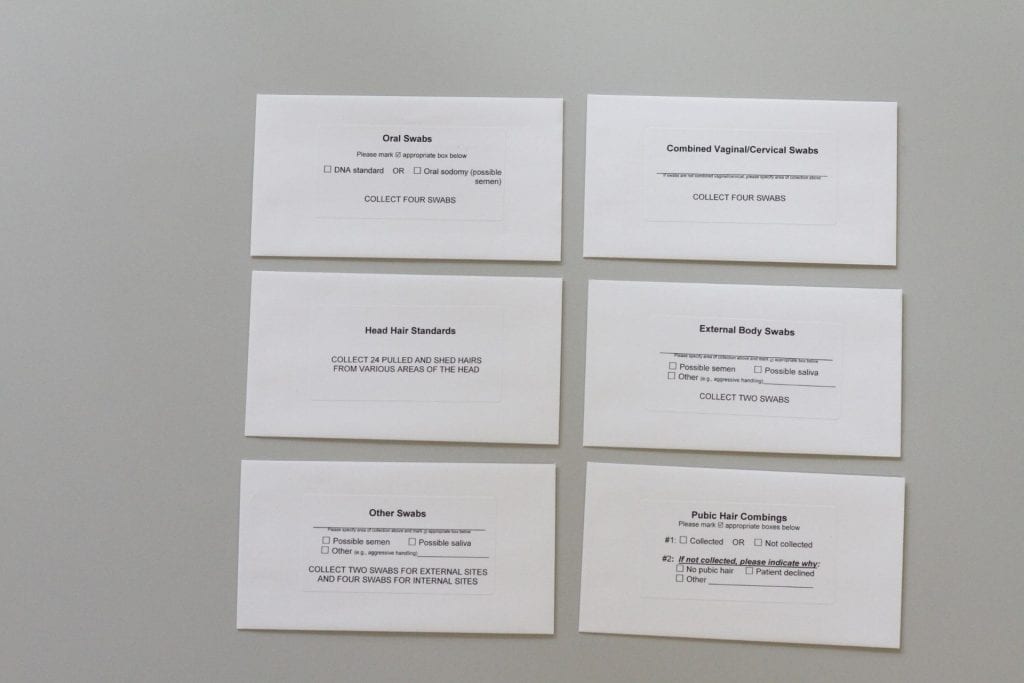

- Evidence is sorted based on the way it is collected. This helps reduce the risk of DNA contamination.

- All SAFE kits come with a comb, ruler, and multiple cotton swabs. Once complete, the test is stored at the hospital until law enforcement comes to pick it up.

When 14-year-old Melissa Bittler was killed by a serial rapist in Portland in 2001, her parents and investigators were dismayed to learn there was untested DNA evidence from two young teens attacked by the same man four years earlier. In 2015, there were 5,654 untested Sexual Assault Forensic Exam (SAFE) kits across the state of Oregon.

Today, that backlog doesn’t exist. As of October 2018, Oregon is one of three states in the country that has cleared its backlog of SAFE kits, which are used to find remaining DNA of the perpetrator on a survivor of sexual assault.

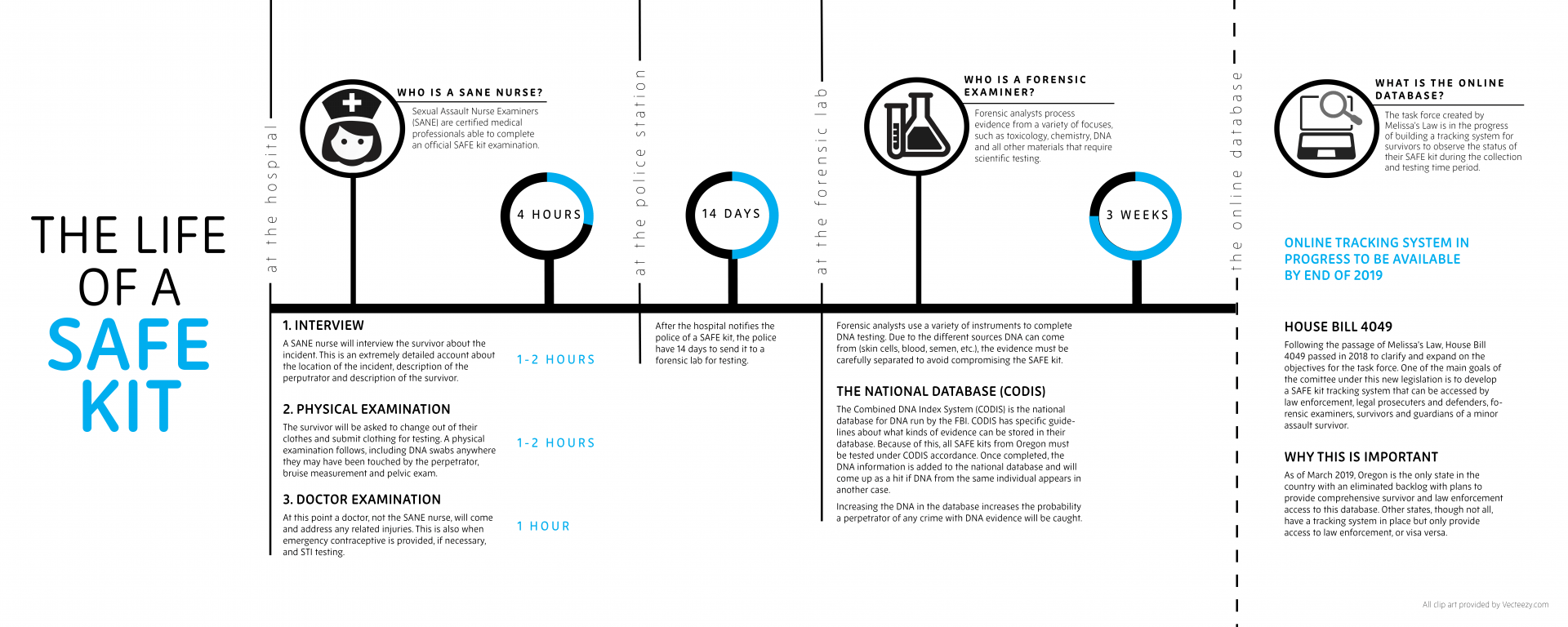

In addition to ending the backlog, all police departments are now required to submit new kits for testing within 14 days of receiving them. The state legislature is also developing an accessible online database for survivors to track their kits. Oregon is the only state with an eliminated backlog that also plans to provide this resource for survivors.

The state of Oregon passed Senate Bill 1571, also known as Melissa’s Law named after Bittler, in March 2016. Melissa’s Law eliminates the backlog of SAFE kits and prevents backlogs from growing in the future through a $2 million federal grant and a $1.5 million state grant.

Bittler’s family had been working with the state to apply for funding with little success. However, in 2015 Oregon was given the federal grant that funded Melissa’s Law and following legislation. According to The New York Times, the Manhattan District Attorney, Cyrus R. Vance Jr., redistributed $38 million dollars of forfeiture money to aid states across the nation in their efforts to eliminate their SAFE kit backlogs.

After the bill was passed, a task force was assembled to examine the collection and testing process and find sustainable funding to ensure the backlog doesn’t pile up after the initial funding ends.

This task force is comprised of two survivors of sexual assault, a forensic examiner, a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE), a defense and prosecution attorney, police, a government funding expert, county and city representatives and a domestic violence victim advocate.

Collecting evidence for the kits is often invasive. However, these kits are essential in cases where the suspect is not known to the survivor or in cases of serial sexual assault, according to research from Michigan State University. Melissa’s Law has streamlined the testing process and held local officials accountable for testing SAFE kits, Tara Gardner, deputy district attorney of Multnomah County, said.

Melissa’s Law, on top of catalyzing the elimination of the backlog, standardized the process of collection and testing system throughout all police agencies in the state. Previously, each police agency had autonomy in their handling of SAFE kits. Police are now required to collect new SAFE kits from the hospital within seven days of being notified. Once in their possession, they must submit the kits for forensic testing within 14 days.

The new requirements have helped regulate the time it takes to get a kit to forensics. But it is here in the lab, while waiting to be tested, that many kits previously ended up being shelved for long periods of time.

When Melissa’s Law was passed, Oregon State Police (OSP) began tracking the time it took to test individual SAFE kits upon arriving in the lab. In 2017, progression on the backlog was actually at its slowest, according to Capt. Alex Gardner, director of Forensic Services. In order to combat the issue of understaffing, Melissa’s Law provided OSP with funding to hire nine full time analysts in 2016.

However, Gardner says the process of hiring new individuals and providing in-house training can take a year and a half, which slowed SAFE kit testing considerably. During this period, it took four weeks to complete individual kit testing. Now, Gardner says the average timeline is down to three weeks, with staff completing 170 to 200 kits a month.

While SAFE kit testing timelines have improved, there is still concern that the forensic division lacks the resources to maintain this efficiency. Kits cost $1,300 each to test, meaning time and money must be spent on each analysis.

Oregon State Police Spokesperson Capt. Tim Fox says keeping up-to-date with all forensic testing is near impossible, likening it to “whack-a-mole.”

The forensic unit is not split up by the type of DNA tested, meaning analysts could be working with SAFE kits one day, and property crime the next. If efforts are put into one form of testing, another can get left behind.

“It’s not a perfect system,” says Fox, referring to the forensic testing department as a whole. “If we had 20 scientists that worked 52 weeks a year, never took any vacation, I mean, we would be good.”

Productive forensic testing is essential to the success of Melissa’s Law and future sexual assault cases. As more DNA becomes available in the national database, the probability of identifying suspects increases.

According to research from Michigan State University, this DNA is pivotal in successfully profiling potential suspects in all cases of sexual assault. While many believe SAFE kits are only useful in identifying unknown suspects, their research revealed that many non-stranger kits were linked to other, previously unsolved assaults.

This research also underlies the importance of DNA testing for cases of serial sexual assault and identifying unknown assailants. In the study of stranger kits, of the individuals identified in the national database, 94 percent were offenders of sexual assault.

Gardner of Multnomah County said that testing SAFE kits can help identify the perpetrator from previous cases that have no other investigative leads.

In Oregon, so far, there have been six cases of perpetrators being identified through the elimination of the backlog, Fox said.

In 2018, Multnomah County police prosecuted Jihad Moore Jr. for two accounts of rape found after testing an untested SAFE kit last October.

“In that case, the testing of the sexual assault kit was the linchpin to identifying the suspect and giving law enforcement the lead that they needed to reopen the case and bring that individual to justice,” Gardner said.

There are some cases that are not prosecutable after the backlog clearance because the statute of limitations had expired, Gardner said. Depending on the year the crime occured, the age of the victim at the time and the age of the perpetrator at the time, a case might not be eligible for legal action.

A Survivor-Driven Process

For survivors, the process of seeking justice with SAFE kits starts at the hospital with their SAFE kit examination.

At the PeaceHealth hospital in Eugene, Ore.,the emergency department is in charge of all SAFE kit testing. Nicole is one of the SANE nurses on call at PeaceHealth and has helped dozens of individuals start this process. She only wanted her first name used due to privacy concerns.

SAFE kits are a compilation of interview questions and DNA evidence; however, specific elements of the kit vary depending on the survivor.

“The process should be driven by the patient,” Nicole said.

While completing an examination she consistently checks in with the survivor. She stresses how important it is to explain why each step is necessary and relevant, especially invasive moments. The survivor can choose which parts of the exam they feel comfortable participating in and may leave at any point.

The exam consists of three steps: an interview describing the incident, a physical examination by the SANE nurse and a doctor examination.

The interview portion of the exam can take anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours. The survivor does not just recount the incident, but also the days prior, and depending how much time has passed, the days following. Questions include the time of their last consensual sexual encounter, the last time they showered and a detailed description of any bodily harm.

After the interview portion of the exam is completed, survivors can submit the clothes they are wearing, often the clothes they wore during the incident, as evidence. The physical examination usually takes about an hour or two. It includes collecting DNA swabs from the survivor and anywhere they were touched from the perpetrator, collecting hairs, bruise measurements, photos taken of bruises and other injuries, and a pelvic exam.

When a survivor comes to the hospital for a SAFE kit examination in Eugene or Springfield, a Sexual Assault Support Services (SASS) ally is contacted and dispatched to the hospital. SASS is a program funded through the city and the state that provides free support services to survivors of sexual assault, harassment or gender violence.

Bianca Marino, an engaging allies coordinator at the SASS office in Eugene, has provided support for many survivors in the area during their SAFE kit examination. Her role, she stresses, is not to help complete the exam, but to assist the survivor in any way they need.

“Interviews can often be re-traumatizing,” says Marino. “They are probably one of the most difficult parts of the exam because they are extremely detailed and redundant.”

For Marino, providing all options for the survivor and detailing the legal process is extremely important at this point. She says many survivors come with the misconception that they have to file a police report or that SAFE kits function as decisive pieces of evidence in their case.

“A SAFE kit will never prove a sexual assault,” Marino says. “It can’t prove lack of consent.”

District Attorney Gardner said in cases that go to trial, SAFE kits are typically only utilized to prove that intercourse occurred. If the perpetrator and the survivor agree that intercourse occurred, but the question of the trial is “was it consensual?” SAFE kits are frequently disregarded.

Melissa’s law also protects anonymous kits from being tested or destroyed without the survivor’s consent. In some cases, survivors do not want to pursue legal action or file a police report. The law now states that kits collected from survivors who do not want to test their kit immediately will be stored for 60 years and can be tested at any time.

However crucial SAFE kits are to the following criminal investigation, Oregon legislators agreed that survivors should have access to their kits’ progress throughout the process.

Oregon legislators say there are plans to introduce an accessible online SAFE kit tracking system. Survivors will be given a tool to track the progression of their SAFE kit through an online database created by House Bill 4049. HB 4049 was created and promoted by many of the same people who pushed Melissa’s Law in 2016.

Along with the development of the online database, HB 4049 expands the task force, enforces sexual assault and SAFE kit training and education programs for police, and identifies potential areas for growth.

Rep. Carla Piluso serves at the chair of this task force and said it will continue to function for as long as it’s needed. The task force was also mobilized to discover a sustainable source of funding to ensure the backlog doesn’t return, which, Rep. Piluso said, has not yet been found.

“This tragic instance allowed for better discussions,” Piluso said referring to the creation of Melissa’s Law, “for not taking anything for granted, for recognizing it’s a real thing, it’s a sensitive thing and it has to be dealt with.”