(This is a preamble to Rose Honey’s curriculum, “Discovering Our Relationship with Water.”)

My name is Rose Honey and I grew up in a small town in Western Montana called Darby. I am an educator with experience in various aspects of education—as an educational researcher, formative evaluator, teacher, curriculum developer, and program developer. My passion in my work is to bring traditional culture and science education together into classrooms for both Native and non-Native children. As a non-Native person, I am very honored to have been given this opportunity to develop this curriculum with the Honoring Tribal Legacies team.

As a young child, one of the activities that I enjoyed the most was collecting rocks. On family outings and just in my backyard, I loved to collect colored rocks, shiny rocks, smooth and interesting rocks – but I also welcomed grey, normal, or what some might call uninteresting rocks to my cherished collection. My parents owned a local hardware store and decided to give me an old Timex watch display case that lit up and had rotating shelves to present my rocks. Each of my rocks had the pleasure of taking turns sitting in the display case, rotating on the shelves and basking in the fluorescent light for all to see. The fancy rocks flaunted their colors and luster proudly. But in my little rock world, the ordinary, everyday grey rocks were also eager for a place on the shelf to sparkle, to shine, and to feel included. Through my work with Native communities as an educator and especially through projects such as this one, I have started to realize that my relationship with these rocks may have seemed insignificant at the time, but these rocks had a lesson to teach to me about differences and variations in the world, and that even if something seems ordinary at first, it should be given a place to sit on the shelf so that it can bask in the glory of the rotating Timex watch display case. This curriculum focuses on the relationship that we have with water—and though we feel water, see it, drink it, bathe in it, brush our teeth with it and use it in various ways every day—it is important to slow down and to recognize that it too has many lessons to teach us.

Through my experiences as an educator, researcher, and student, the things that I have come to value above most things are my relationships – with family and friends, with students, and in general with the world around me. I see now that as a young girl, I also had a relationship with these rocks. And that as I was growing up, the rocks were telling me a story about taking care of people, and teaching me that no matter what our color or how sparkly or dull we think we are, if we are given our own shelf to sit on so that we can display our unique qualities, we too will shine. This is a good way to think about my philosophy on education. I believe that the opportunities that we are given and the ways that these opportunities are presented will result in how much we shine. This is why it is so important to bring Native perspectives into classrooms and give children the chance to look at the world through a Native lens. My hope is that by offering children the opportunity to experience the world through relationships, in ways that are familiar to their histories and their cultures – children, as well as their parents and their teachers, will be actively engaged in learning that focuses on bringing worlds and educational disciplines together.

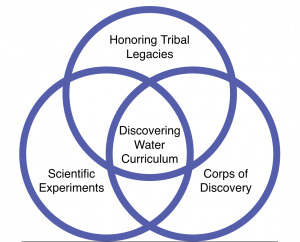

The sacred hoop is used to illustrate the water curriculum, incorporating the three components: honoring tribal legacies, scientific experimentation and the corps of discovery.

This curriculum focuses on early learning and science education that honors Tribal Legacies through our relationship with water. In my experiences with research and education related to Native education, my focus has been on describing and exploring the notion that some Native students who hold traditional worldviews can sometimes have difficulty “crossing the border” into a scientific worldview in their classrooms (Aikenhead & Jegede, 1999). Ways of thinking about the world may differ or even conflict with the ways of life that students experience at home, compared to thinking and behavior expectations at school. As I developed this curriculum and incorporated Native worldviews into each lesson, I struggled to recognize whether or not I was thinking about these concepts “correctly.” It occurs to me that I, myself, am border crossing as a curriculum developer. Experiencing this gives me a window into how it must feel for children who are asked to think about the natural world in ways that feel foreign or vague to them.

In developing each lesson plan, I focused on the Big Ideas that I had decided to explore in this curriculum (connections, balance, transformation, cycles, reciprocity, and relationships) and thought about what scientific experiments would be engaging for young children. Then I tied each Big Idea (and experiment if possible) to the Lewis & Clark and Corps of Discovery journey. As I developed each lesson, I thought about how to balance teaching science without taking away from larger ideas that focus on honoring tribal legacies. One method that I encourage using is to learn words and phrases for scientific processes in the local Native language, and then integrate these into your teaching by posting the words on the walls, practice saying the words with the children, and making a point to use the words while doing experiments in class. Each lesson plan includes some words and phrases from tribes mentioned in the activities. However, it is important that words and phrases from the local language that are related to the places you are teaching about are integrated into these activities.

My life has taken me to many places in the world where I have had the opportunity to meet all kinds of people. My experiences remind me over and over again that people may speak different languages and have different cultures, but they also have a lot of similarities. People want to make connections with one another and they want to be understood. This realization has helped me in this type of work as I have learned to build relationships with the people in the communities that I am working in, and reach out to people and ask for their help when I need it. I have also learned that asking Elders or community members for knowledge or information is sometimes the same as asking for people’s treasure that they hold very near and dear, and this knowledge should be respected as such.

My hope is that this curriculum will be utilized by Native and non-Native teachers alike. If you are a Native teacher, I hope that you will find new ways to help your fellow non-Native teachers to bring the local culture into their classrooms. Perhaps you can help them to pronounce some tribal names or words, or maybe have a discussion with them about some of the ideas included in these lesson plans—such as transformation or reciprocity. And, if you are non-Native, I encourage you to reach out to the Native community around you and invite them into your classrooms. Any way that you are able to reach out will build stronger relationships with other educators and will ultimately help the children. When teachers are connected through strong relationships with their students, they are also able to connect them with the subject area that they are teaching.