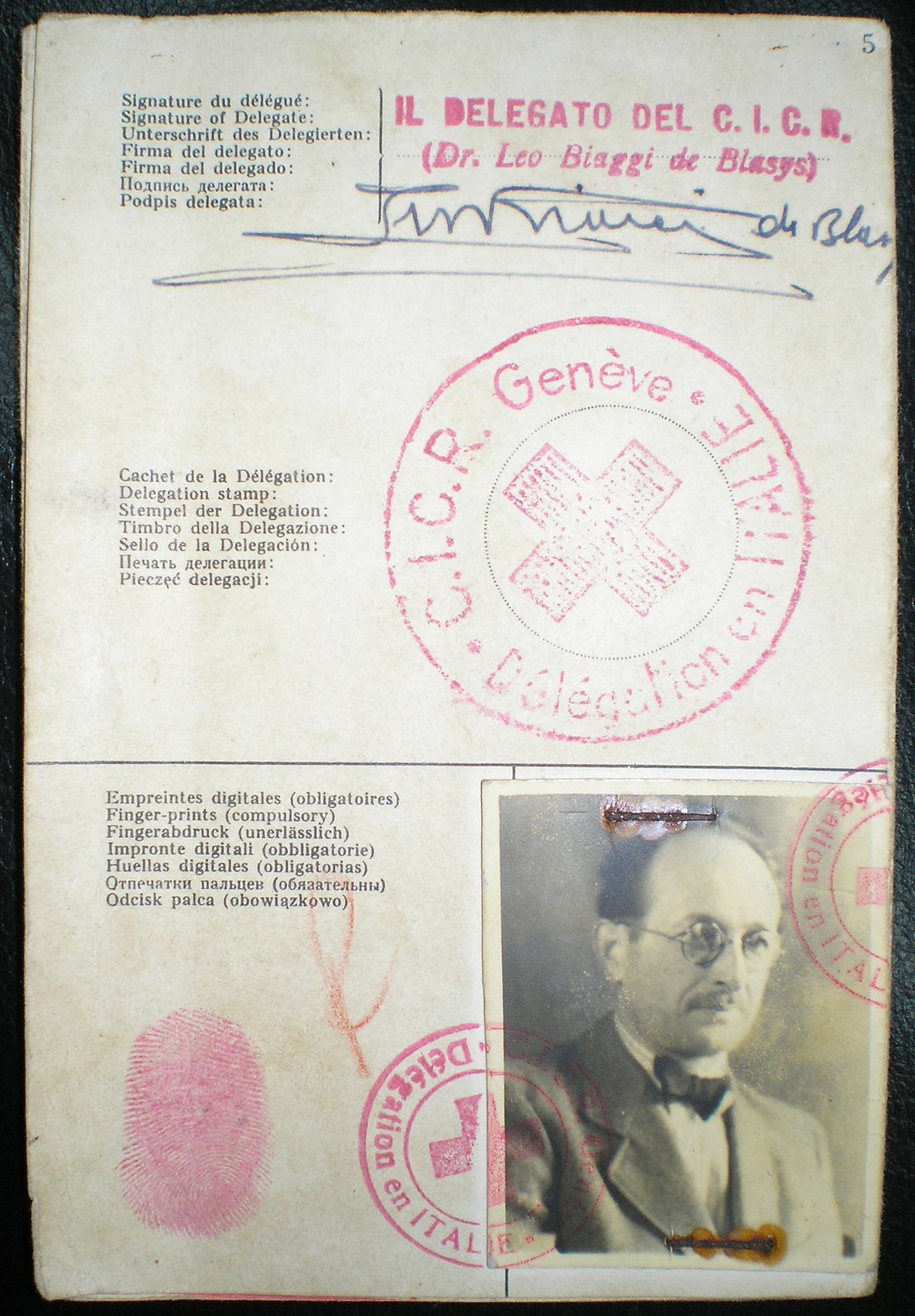

Nazi S.S. Adolf Eichmann’s Passport used to enter Argentina in 1950. – Holocaust Memorial Foundation, Buenos Aires Argentina

S.S-Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Adolf Eichmann was an integral part of Hitler’s Final Solution. Throughout the Second World War, Eichmann was specifically tasked with the facilitation, management, and mass deportation of Jews to both ghettos and extermination camps. He evaded his 1961 capture for 15 years through his infamous 1950 immigration to Argentina. Behind a bulletproof glass booth he was tried in Israel, found guilty for both war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentenced to death, and executed in 1962. Subsequently, as Paul Jaskot explores in this peer reviewed article, theorist Hannah Arendt conducted a detailed research study on Eichmann. She examines, among other things, Eichmann’s psychological profile and internal persona.

According to the Holocaust Memorial Foundation from which this document originates, Argentinean Judge Maria Servini de Cubria discovered Eichmann’s fake passport in 2007. Subsequently, she turned it over to the museum in recognition that it was documentation of historical significance. This alternate identity document does not have a distinct bias but rather a specific use. Created explicitly for Eichmann by the Italian delegation of the Red Cross, it was produced in the distinct socio-political context of the Nazi regime’s defeat. This forged passport, issued in 1948, served as a vital escape route from inevitable prosecution for crimes against humanity. While the document’s written text appears in a variety of languages, the distinct pink fingerprint and large seal of approval states that Eichmann successfully entered Argentina in 1950 under the alias Ricardo Klement.

As a source created in the specific context of Nazi escape, the original audience of Eichmann’s fake passport was Argentinean immigration authorities. Today, the preserved document is publicly displayed in the Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum, effectively targeting both a national and international public audience.

This particular document is in direct conversation with Argentina’s recognition as a country of refuge for not just fugitive Nazis, but any and all European immigrants. The document itself demonstrates to historians that the history of Argentinean immigration emphasized the conceptual practice of European immigration, ignoring the individual immigrants or the ways in which they entered the country. In a global context, this document can aid in examining post-World War II immigration on a narrow scale, focusing on the migratory exchange of Nazi criminals between Europe and South America.

–Clara T. Gorman