Panel One: The Human Sciences in Colonial Context

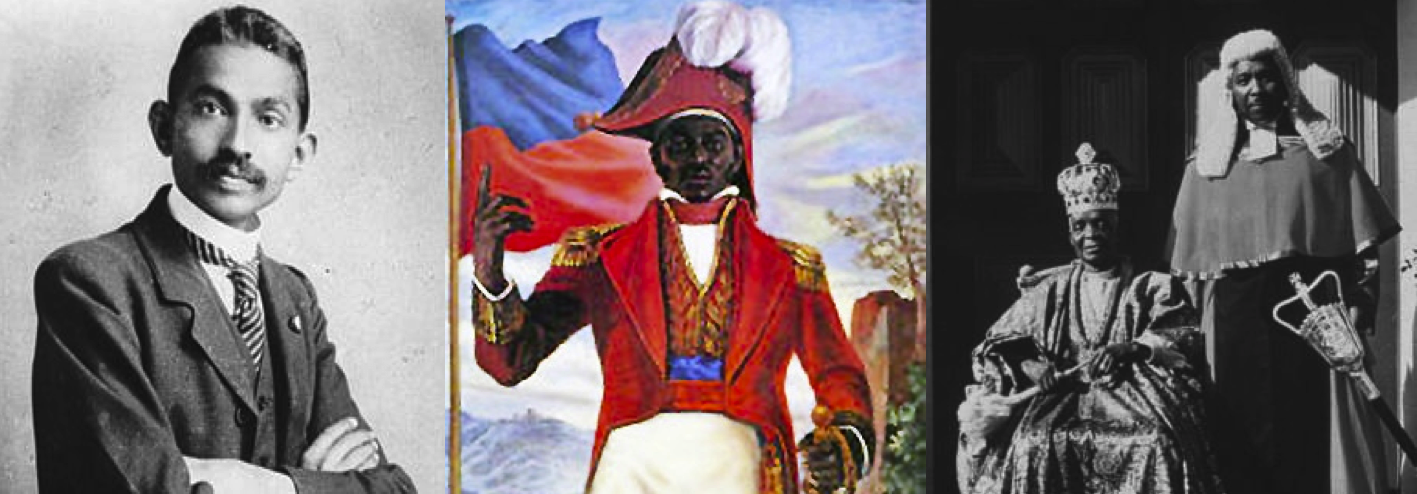

Inder Marwah (McMaster University), “Re-thinking Resistance: Darwin, Spencer and The Indian Sociologist”

- The political harms of Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory – particularly in light of its association with the “survival of the fittest”, drawn to prominence by Herbert Spencer, and the social Darwinism built upon it – have been well chronicled. Darwin’s and Spencer’s influence over late 19th and early 20th century political thinking is understood to have lent credence to, and even further entrenched, imperialist expansionism by buttressing the view of colonized peoples’ “natural” inferiority. In this paper, I recover a strain of Darwinian political thinking that, instead, stood against the project of empire. I draw on the work of a group of radical Indian nationalists, activists and thinkers surrounding an anti-colonial journal entitled The Indian Sociologist to explore their appropriation of Darwin’s and Spencer’s thought in resisting both the imperatives of British imperialism and the quiescence of 19th century Indian liberalism. The paper aims (1) to recover a strand of Darwinian political thinking that opposed the determinism of social Darwinism, (2) to show that Darwin’s and Spencer’s ideas were not only taken up by European imperialists, but also by non-Europeans in resisting them, and (3) that this constituted a distinctive form of political resistance equally set against British colonialism and the Indian liberalism prevalent in the era’s nationalist and anti-colonial circles.

Megan Thomas (University of California – Santa Cruz), “Impurity in Translation: Late Nineteenth-Century French and Filipino Appropriations of Lamarck”

- This paper traces the strange and sometimes contradictory ways that scientific theories and political arguments traveled across different political contexts. In the late nineteenth century, the young Filipino intellectual Pedro Paterno wrote creatively about the ethnology and history of the Philippines, arguing that history revealed that particular qualities were inherent to certain races and racial mixtures, and further arguing that one such group of the Philippines was doomed to extinction while another was destined for a bright future. His arguments derived from contemporary French political and intellectual debates about race in the context of anti-Semitic nationalism, which themselves creatively appropriated the conclusions of the earlier Lamarck. But the connections are not as straightforward as they might seem: Paterno used arguments that opposed each other in the French context to support his claims about the contrasting qualities and so destinies of these two groups in the Philippines.

Discussant Comments, Lindsay Braun (University of Oregon)

Keynote Paper I:

Lynn Zastoupil (Rhodes College), “Intellectual Flows and Counterflows: Early Nineteenth-Century India, Britain, and Germany”

- This paper explores the flow and counterflow of ideas, texts and people between Britain, Germany and India in the early nineteenth century. Employing the overlapping examples of H. H. Wilson, A. W. Schlegel, J. S. Mill and Rammohun Roy, it examines colonialism’s role in fostering transnational intellectual networks and political campaigns. Indian agency in the construction of colonial knowledge and policies is also addressed through the example of Wilson’s Indology. Another theme is the multiple intellectual interests—including Indian traditions of Sanskrit studies, colonial administrative practices, Romanticism, and German Indology and hermeneutics—that linked Wilson, Schlegel and Mill. One result of these shared interests was the collaboration of Wilson and Mill on a defense of Sanskrit studies that blended Indian scholarly traditions and political sentiments, imperial pragmatism and Romantic nationalism. It then turns to Rammohun Roy’s transnational fame in the 1820s and 1830s. The British religious and political networks that welcomed and celebrated the Bengali reformer provided him and Mill with common friends and causes, including a transnational campaign for liberty of the press, to which both men made important contributions in the 1820s. Yet Mill was silent about the famous Bengali. It concludes by addressing briefly that silence in light of Mill’s mature works where colonial despotism is endorsed and Indians (and others) are deemed unfit for liberty.

Panel Two: The Master’s Political Tools

Jimmy Casas Klausen (Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro), “Naïve or Canny Monarchism? Mahatma Phule, Thomas Paine, and Appeals to the Queen”

- “Naïve monarchism” names the phenomenon of subalterns’ appealing to a distant and venerated authority—usually the officially sovereign authority—against local, disrespected authorities, officially subordinate to the sovereign yet in effect exercising ultimate power because of the latter’s remoteness and consequent obliviousness to the local sufferings of her or his subjects. Often more than isolated longing (although there is power, too, in that), naïve monarchism can provoke slaves, outcastes, and peasants to generate new political realities, but its politics is almost always paradoxical, especially in colonial situations. This paper explores the license and limits of naïve monarchism as a political force by examining Jyotirao Phule’s simultaneous appeal to Queen Victoria and inspiration by the anti-monarchist Thomas Paine in the dialogue Slavery (Gulamgiri, 1873), which diagnoses and analyzes high caste persons’ oppression of members of the lowest castes and outcastes. Was Phule really naïve or a canny political thinker and actor? When, why, and from what perspective might it seem empowering to recognize one conqueror (the British) against a prior one (Brahmins)?

Johnhenry Gonzalez (University of South Florida), “The New World ‘Sans Culottes’: French Revolutionary Ideology in Saint Domingue.”

- Aimé Césaire writes that it is “the worst error to consider the Revolution of Saint Domingue purely and simply as a chapter of the French Revolution.” On the other hand C.L.R. James emphasizes both the adoption of liberal-democratic ideology by Caribbean slave insurgents and the radical universalism of the French Jacobins’ February 1794 act of slave emancipation in claiming that Saint Domingue and revolutionary Paris briefly constituted two allied wings of a fully transatlantic revolutionary movement. By discussing both the adoption of European liberal-democratic rhetoric by Caribbean insurgents as well as the language of universalism that accompanied the 1794 French emancipation decree, this article explores some of the strongest examples of direct ideological linkages between the French and Haitian revolutions.

Sankar Muthu (University of Chicago), “Transcontinental Chains and Transformations: On Resistance Against Global Domination in Quobna Ottabah Cugoano’s and Immanuel Kant’s Political Thought”

- Despite what is often considered to be the boundless optimism about human nature in Enlightenment thought, many eighteenth-century thinkers believed that a domineering tendency was fundamental either to the human condition or to the civilized condition of sedentary agriculturally-based societies. The paper begins by offering an analysis of Immanuel Kant’s theory of unsocial sociability, domination, and resistance, which informs his account of the global condition of the modern age. It then turns to the writings of Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, a former slave who eventually settled in London and published in 1787 a remarkable book on slavery (Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery). In a more sustained and far-reaching manner than any English anti-slavery activist of the period, Cugoano diagnoses the ills of modern slavery through the lens of global commercial and imperial interconnections. In their own distinctive ways, Kant and Cugoano exemplify an intriguing and complex strand of Enlightenment thought that views global connections as both corrosive to our shared humanity and yet essential for resisting the kinds of domination that simultaneously afflict both European and non-European peoples.

Discussant Comments, Lynn Zastoupil (Rhodes College)

Discussant Comments, Sue Peabody (Washington State University-Vancouver)

Keynote Paper II:

Bonny Ibhawoh (McMaster University), “‘Only the Wealthy and Wicked go to the Privy Council’: Colonial Contestations of British Imperial Justice”

- Writing in 2012, the Jamaican jurist Patrick Robinson, argued his country to replace the Judicial Committee of Privy Council (JCPC) with an independent Caribbean Court of Justice as its highest court of appeal. In his view, the Privy Council was a symbol of outdated British imperialism. His critique focused on access to justice. “It was only the wealthy and the wicked who go to the Privy Council,” Robinson reasoned. This critique typifies earlier twentieth century imperial debates about the relevance of the Privy Council in the administration of justice in the colonies. This topic dominated discussions at the Imperial Conferences and shaped the 1931 Statute of Westminster. At a time when dominion governments were keen to remove the remaining vestiges of colonial status, the relevance of the JCPC became a disputed issue. To some, the JCPC was an indispensable ‘link of Empire’; the central connector between the distant constituents of the British Empire; a symbol of enlightened association based on Common Law. To others, however, the JCPC was a symbol of English elitism and an obsolete imperial order. From Canada to Australia, from Ceylon to South Africa, administrators, judges, the press and ordinary citizens weighed in on the subject. This paper examines the debate in the dominions and colonies over access to justice at the Privy Council, focusing on concerns about cost, delays, distance, and procedures.

Panel Three: Conscripting the Tools of Critique and Reform

Murad Idris (University of Virginia), “Qasim Amin on Colonialism, Progress, and Empire”

- This paper situates Qāsim Amīn (d. 1908) on religion, gender, class, and race in relation to colonial exchange and domestic critique. Amīn is sometimes touted as a liberal proto-feminist reformer, more often dismissed as a patriarchal anti-democratic Europhile caricaturing Islam. I approach his writings in layers, as a locus for local and transnational discourses, also reading them through: (a) his famous exchange with the Duc d’Harcourt over Egyptian culture; (b) the European thinkers he adapts (Spencer, Darwin, Mill, Comte, Montesquieu, Renan), their own references to Arabs, Islam, or Egypt; (c) European reviews of Amīn’s work; and (d) his oeuvre’s reception among Arabic-writing contemporaries, particularly the accusation that he was posturing as “the Muslim Luther.” I argue that Amīn’s uses of the powerful word “No” only saw power peripherally; like his admirers and enemies, he accepted the language of “religious,” “national,” or “civilizational” progress, pegging each to newly emerging social categories.

Yasmeen Daifallah (University of Massachusetts-Amherst), “Marxism as Pedagogy: Abdullah Laroui’s Appropriation of the Early Marx”

- Like many of his generation of Arab thinkers, the Moroccan historian Abdullah Laroui (b. 1933) is usually thought of as a Marxist turned liberal, or, by some accounts, a Marxist turned etatist. This change of heart is usually explained in terms of Laroui’s supposed adaptation to the ever-changing tides of Arab politics. Yet these interpretations miss Laroui’s peculiar appropriation of Marxism for an Arab context. Chosen on pragmatic grounds, Laroui conceives of Marxism less as a political truth, and more as a theory of history that works best to educate the Arab intellectual about historical change, and to provide a tool to instill that change through overcoming the state of “cultural retardation” of the Arab condition, as Germany once did. Understood this way, bourgeois liberalism is but one “stage” in the multi-stage process of historical change that should be directed (by the intellectual and/or politician) towards a more egalitarian cultural and political order.

Discussant Comments, Jonathan Katz (Oregon State University)

Generously sponsored by the College of Arts and Sciences, the Department of Political Science, the Department of History, the Department of Philosophy, the Department of Romance Languages, the Department of Anthropology, International Studies, African Studies, Asian Studies, Latin American Studies, European Studies, Center for Latina/o and Latin American Studies, and the School of Law.