Temple Grandin is probably the best-known individual with autism in the United States today, and perhaps in the whole world. She came to popular attention after neurologist and author Oliver Sacks profiled her in a 1993 New Yorker article, “An Anthropologist on Mars.” Grandin used that catchy term to describe how bewildering she found the rules governing normal social interaction. She had to study other human beings as anthropologists do, as participants in a different culture, in order to learn those rules.

At the time, few if any individuals with autism had described their lives in their own words. Grandin’s story was utterly astonishing. She revealed how impossible it could be for her to understand other human minds and, at the same time, how capable she was of using her exceptional intelligence to do exactly that. Grandin helped lay the groundwork for concepts like neurodiversity. Since the 1980s, Grandin’s story has made her a role model for individuals with autism and an inspiration for millions more. She has literally expanded the definition of what makes us most human.

Except for her gender, Grandin exemplifies many features of Asperger syndrome. Her ability to concentrate sustained attention on very specific, technical subjects has made her incredibly successful in her chosen field, animal science. She graduated from Franklin Pierce University in 1970, earned an MA from Arizona State University in 1975, and a PhD from the University of Illinois in 1989. Now Professor of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, Grandin specializes in designing humane livestock handling and slaughtering facilities and has also created a scoring technique to assess how successful humans are in reducing animals’ stress in meatpacking plants. Grandin’s designs are used in approximately half of all cattle-processing plants in the United States. She is considered one of the world’s foremost authorities on the welfare of cows and pigs and has published hundreds of articles in her field. Her contributions to agriculture have won acclaim from industry leaders and admiration from animal welfare advocates.

For Grandin, animal welfare and autism are intimately linked through her own life experience. Grandin describes her brain as a video library, a characteristic she credits for her ability to solve visual puzzles that others easily miss and empathize with animals who also “think in pictures.” Years before Sacks wrote about Grandin, she reached out to autism researchers and clinicians, trying to make her condition more comprehensible. “Did you ever wonder what an autistic child is thinking?” she asked in 1984 at the beginning of the first essay she published about her childhood, in The Journal of Orthomolecular Psychiatry. “I was a partially autistic child and I will try to provide you with some insight.”

Grandin has written eight books, many of them at least partly autobiographical, and speaks frequently at autism conferences and events devoted to animal science and welfare. Her awards and honors are numerous. Grandin has been interviewed in scores of magazines and newspapers and profiled on 20/20, 60 Minutes, and Today. She has been the subject of several documentaries as well as a 2010 biopic starring Claire Danes. Her 2010 TED talk is subtitled in 36 languages and has been viewed almost five million times.

Born in Boston, Grandin did not speak until the age of three and one-half. Instead, she screamed, hummed, engaged in repetitive behaviors, and threw destructive tantrums. She was fearful of hugs and flinched when touched. When she was diagnosed with autism in 1950, her parents, Eustacia Cutler and Richard Grandin, were encouraged to institutionalize her. Temple’s mother refused. She was determined to teach her daughter to talk and learn fundamental social skills: dressing herself, using table manners, taking turns, shaking hands, saying please and thank you, and being on time. She would not allow Temple to disappear into a world of her own. With the help of a nanny, she insisted on yanking her back into the social world. Temple Grandin’s mother did first what Clara Park later described in her famous memoir, The Siege: she battled her daughter’s autism.

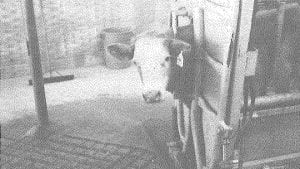

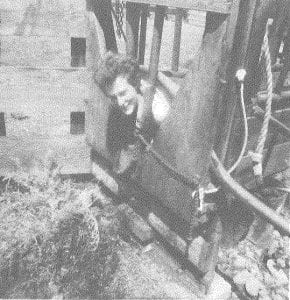

By Grandin’s own account, other supportive mentors played key roles in her life. High school science teacher William Carlock took her seriously and encouraged her to pursue the construction of a “squeeze machine.” As early as age five, Grandin recalled daydreaming about a mechanical device that would provide more bodily pressure than the blankets or sofa pillows she wrapped around herself at home. The machine Grandin eventually designed and built for herself when she was 18 was modeled on a cattle chute she saw on her aunt’s Arizona ranch. After cows were led into the chutes, the machines closed around the animals’ bodies, pressing their sides to calm them.

Grandin perfected her squeeze machine over a number of years and made it the subject of her undergraduate thesis. Equipped with a padded neck opening, a comfortable headrest, and completely lined with foam rubber, it allowed her to manually control the tactile sensations she both needed and feared. The machine helped her tolerate firm touch, which in turn allowed her to feel and, ultimately, become closer to other human beings. “Unless I can accept the squeeze machine I will never be able to bestow love on another human being,” she wrote in college.

Grandin’s first squeeze machine under construction. She built it out of scrap wood while she was in high school.

The machine led Grandin to think about her autism as a problem of the central nervous system, with symptoms related to sensory regulation. Autism existed when individuals routinely over-reacted to a flood of sensory information—sounds, sights, smells, and touch—that their brains could neither tolerate nor process. Anti-anxiety drugs like librium and valium had no effect on Grandin, but her squeeze machine worked. By allowing her to manage sensory input herself, it comforted but did not overwhelm her. It combined two things that autism made incompatible—stimulation and relaxation—and gave her greater access to the social world.

Grandin’s narrative began circulating during the 1980s, when she was in her forties, but she was diagnosed in 1950, when psychogenesis dominated thinking about autism. At that time, autism was widely considered to be a product of faulty or failed attachment between parents, especially mothers, and their infants. That Grandin’s mother had the strength of character and determination to insist that Temple learn to speak and adapt herself to ordinary social and educational environments makes her almost as inspiring a figure as her daughter. It certainly places her among other pioneering parents and relatives, including Clara Park and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, whose efforts paved the way for the attitudinal and policy changes that made deinstitutionalization a reality and community integration a feasible goal.

As autism’s cultural visibility has increased in recent years, so too has the number of first-person narratives from individuals with autism. But Temple Grandin remains a unique figure whose powerful voice has indelibly changed, for the better, what Americans think autism is and what it means.