Norwegian-born Ivar Lovaas immigrated to the United States as a young adult in 1950. As a teenager, he witnessed the German occupation of Norway and wondered whether such destructive behavior originated in nature or nurture, a question he later identified as the source of his interest in psychology. He completed his PhD at the University of Washington in 1958 and held a postdoctoral position there in the Institute for Child Development. Lovaas spent his entire professional career after that at UCLA and was a founder of the Autism Society of America in 1965. His dedication to severely affected children who were considered hopeless and untreatable earned him admiration even as his research attracted criticism. The “Lovaas method” was an important foundation for Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), now the leading paradigm in early intervention for children with autism.

Guiding Lovaas, his students, and colleagues was the behaviorist tenet that all behavior is systematically shaped by its consequences. “When a child emerges as a human being,” Lovaas wrote, “he does so essentially on the basis of the effect of his behaviors on his social environment.” That social environment consisted of people and those people responded to children with rewards and punishments that were predictable and measurable, making it possible to modify behavior by systematically altering the “reinforcement schedules” that shaped it.

The implication was that desirable behaviors could be elicited in children who did not display them—by offering cookies or praise when kids performed as desired—while undesirable behaviors could be eliminated or reduced—either by withdrawing positive reinforcement or by scolding, spanking, or taking other punitive steps. His behaviorist orientation led Lovaas to believe that severely disabled children learned just as normal children did. He even speculated that labeling them autistic might be a factor in eliciting the behavior it meant merely to describe.

B.F. Skinner had already suggested that techniques of operant conditioning, well established in the field of animal behavior, could be applied to human learning and development by the time that Lovaas began his research. Children with autism would have been considered the least promising candidates. Why? Individuals with autism appeared oblivious to their social environments and unaffected by the motivation that made reinforcement matter.

When Lovaas arrived at UCLA in 1961, he wanted to conduct an experiment on language learning and needed children old enough to speak who did not. He was referred to the university’s Neuropsychiatric Institute, where he first encountered children with autism. “As if in a dream, I had found the ideal persons to study,” he remembered. Non-verbal children were perfect subjects because teaching speech to these children, presuming it could be done, would provide many more opportunities for them to engage with their environments.

“I had found the ideal persons to study,” Lovaas recalled, “persons with eyes and ears, teeth and toenails, walking around yet presenting few of the behaviors that one would call social or human.” (courtesy of Life Magazine)

Through the Institute, he identified other non-verbal children at Camarillo State Hospital. During his first year there, he concentrated on only one patient, 9-year old Beth. That made it feasible for Lovaas and his students to work with her for six hours every day, five days a week. Beth allowed Lovaas to develop the method of scoring multiple behaviors in real time and perfect a design for single-subject experiments.

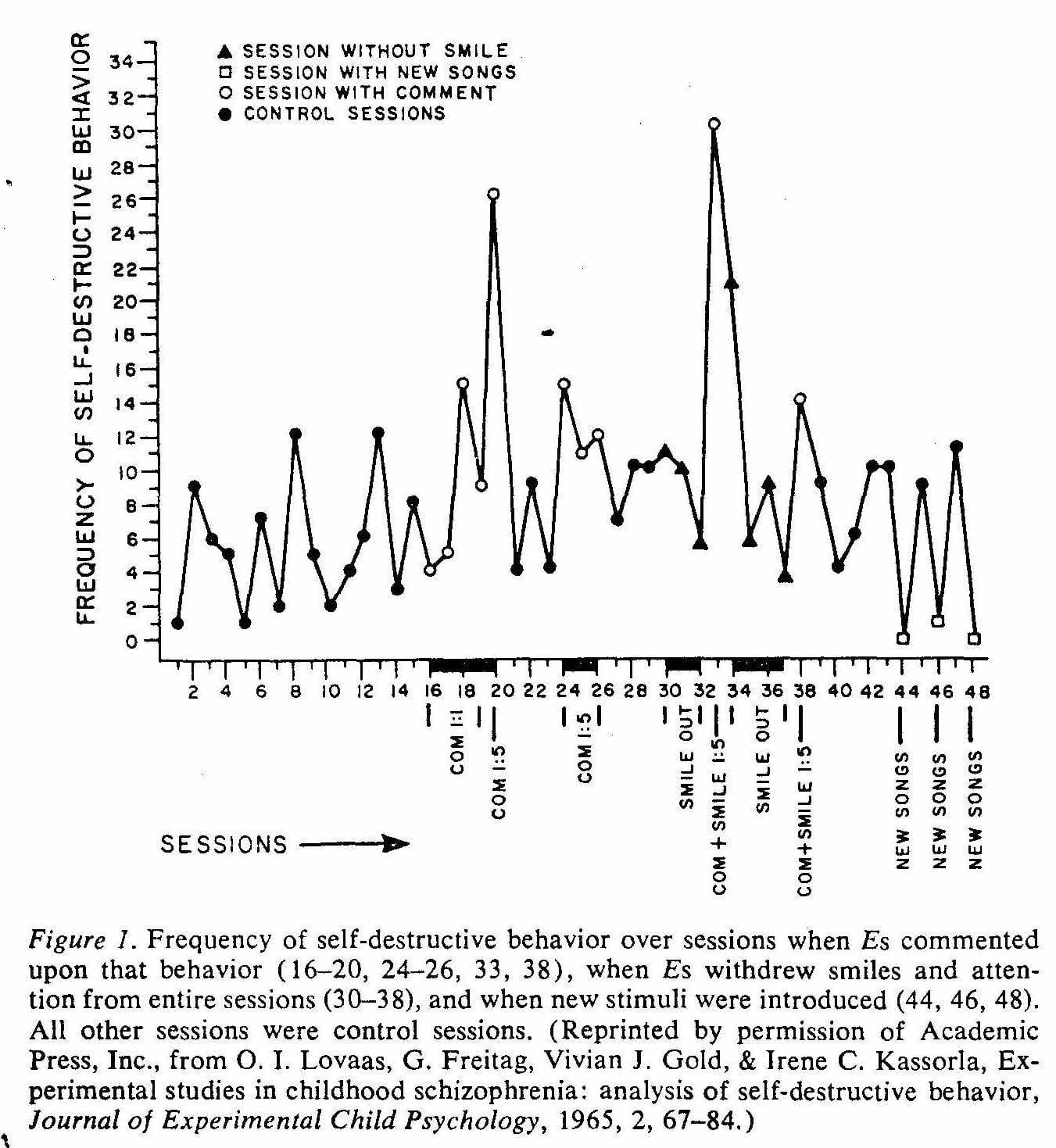

Beth was echolalic (able to repeat sounds and words made by others), so she was not entirely devoid of speech. Using food as reinforcement, Lovaas taught her 50 new words in just a few months. This was impressive, but there were at least two major obstacles to further progress. First, Beth’s family members could not adjust to the demanding regimen of behavioral reinforcement that Lovaas had established. Given how time-consuming and monotonous that regimen was, this was hardly surprising. More surprising was the second discovery. All the attention lavished on Beth during weeks and months of intensive work had unintentionally increased her tendency toward self-mutilation. Lovaas noticed that ignoring Beth’s “psychotic” behaviors would eventually lessen their frequency. (Withdrawing positive reinforcement in order to reduce a behavior is what behaviorists called extinction.) One can only imagine the worry that Lovaas and his students must have felt while trying not to respond to a child who banged her head repeatedly and violently against walls and furniture.

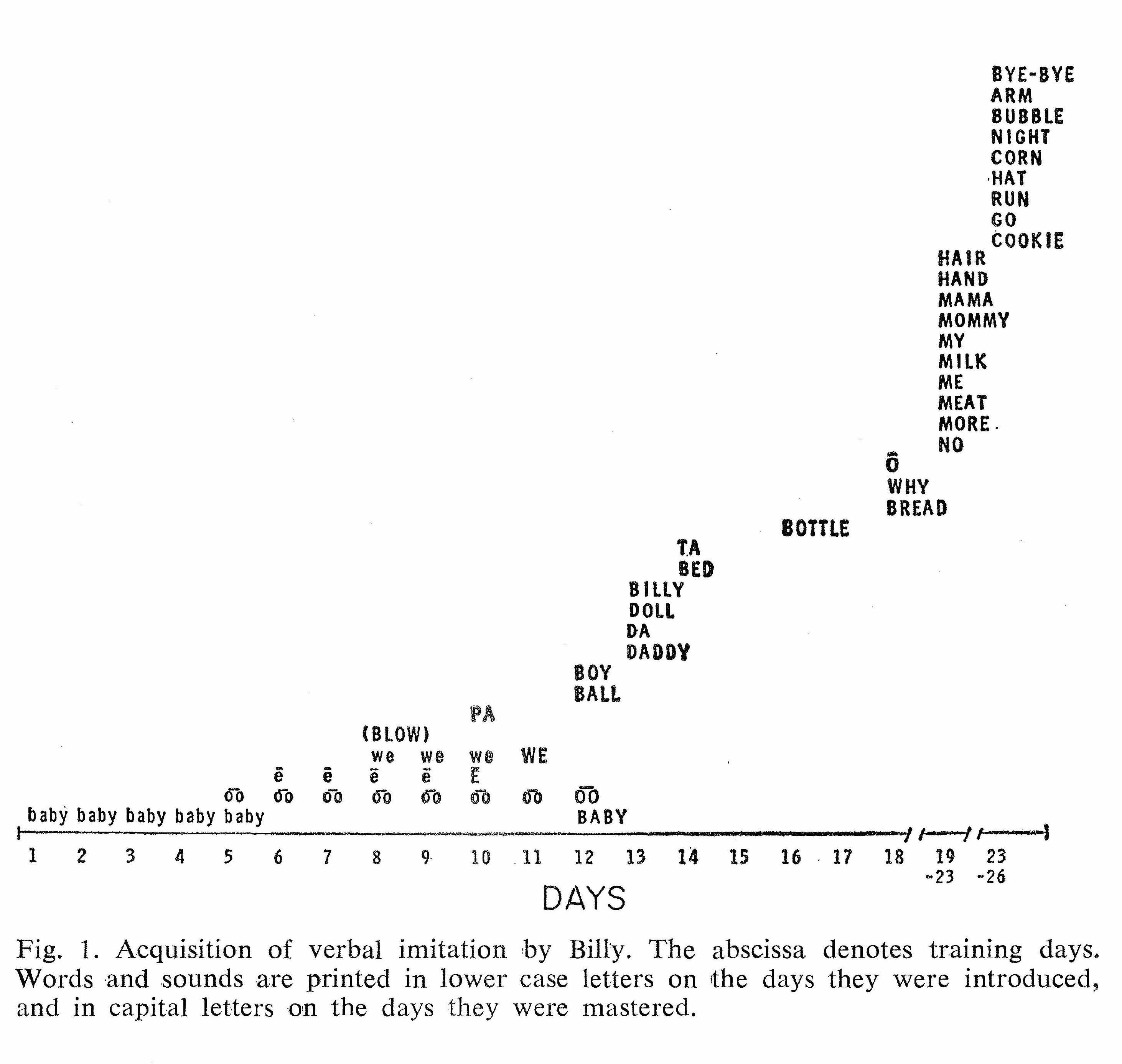

After Beth came other children. Lovaas worked with two 6-year old institutionalized boys, Billy and Chuck, to determine if vocal imitation could be taught in completely non-verbal children through the use of reinforcement. Chuck and Billy got faster and better at imitating sounds and simple words as the training progressed, but even Lovaas admitted that there were limitations to teaching children vocal response when they had no idea what any of the words meant and could not use them to express needs or desires.

If non-verbal children weren’t challenging enough, Lovaas also worked with children whose self-harming behavior was extreme. They tore out hair and nails, bit themselves to the point that fingers had to amputated, and banged their heads so violently that their scalps were covered by scar tissue. Considering the pain and damage these children experienced, and the fact that a number had to be constantly restrained for their own protection, Lovaas looked beyond positive reinforcement. Several of the children would literally engage in thousands of repetitions of self-abuse before extinction began to work, so using that technique meant allowing the children to hurt themselves until they slowed or stopped. The potential for harm was so high in some cases that he decided against taking the risk.

Lovass presented detailed data about how his experimental subjects responded to behavioral reinforcement. This example from one of his early publications documents the rate at which one boy, Billy, learned to imitate words.

Lovass presented detailed data about how his experimental subjects responded to behavioral reinforcement. This example from one of his early publications documents efforts to reduce self-destructive behaviors in one child.

With no benign alternative available, Lovaas considered negative (or aversive) reinforcement. It began during the year he worked with Beth at Camarillo State Hospital. The first time Lovaas saw her bang her head against the sharp corner of a steel cabinet, he “reached over and gave her a whack on her behind with my hand.” Lovaas acted spontaneously, without thinking, and felt “intense fear and guilt as to what I had done.” But he also remembered thinking that he would never have permitted any of his own four children to behave as she had. When Beth quickly stopped her head-banging, Lovaas was relieved. He had learned that aversive reinforcement might free children, perhaps making it possible for them to function with fewer restraints and in less restrictive environments.

Lovaas incorporated quick slaps on hands or bottoms into his research, but the quantity of this reinforcement (not to mention the possible injuries inflicted) could not be precisely controlled. In his quest for more consistent aversive techniques, Lovaas experimented with electric shocks administered through electrified floor grids and small remote control devices taped to children’s wrists. The most satisfactory technology was a hand-held instrument called the hot-shot. It was applied quickly to a child’s leg, delivering a painful, one-second shock.

The experimental data persuaded Lovaas that aversives could alter negative behaviors quickly, and that was very compelling in cases of children whose destructive behaviors were directed against themselves. “Isolation or electric shock may seem harsh, but these are ‘acts of affection’ for children who have spent large parts of their lives hurting themselves.” Parents gave Lovaas permission to use negative reinforcement and became some of his strongest supporters, especially when his work made a discernable difference in the quality of their children’s lives. Everyone understood that this approach was a last resort, to be used sparingly and only after positive reinforcement had failed.

The work Lovaas did created ethical dilemmas for clinicians, teachers, and parents. If punishment worked, why not use it with all autistic children? Could parents who found Lovaas’ approach intolerable conscientiously restrict themselves to positive reinforcement, knowing that children’s harmful behaviors might well persist, requiring additional restraints and restrictions? These disturbing questions made Lovaas a lightning rod for controversy. A 1965 profile in Life generated passionate defenders as well as horrified detractors.

Among autism researchers, Lovaas became best known for his 1987 report about the positive long-term results among children he started treating in 1970. In the Young Autism Project, one group of 19 children had been subjects of intensive, one-on-one treatment during most of their waking hours for several years prior to entering school. Their parents worked as part of the treatment team and committed themselves to maintaining the strict regimen at home, 365 days a year. A comparable group was treated for 10 or fewer hours per week. The goal was to see whether intensive treatment could help the children catch up developmentally by the time they entered first grade. During year one, treatment concentrated on reducing self-harming and stereotypical behaviors, responding to simple verbal requests, and learning imitation. Year two emphasized verbal communication and interaction with peers. Appropriate emotional expression was highlighted during year three, along with the rudiments of reading, writing, and math. This sequence sought to maximize children’s potential for success in ordinary schools by giving them a big head start.

What were the results? Of the participants in intensive preschool treatment, nine (47%) performed normally in first grade, had normal I.Q. scores (a full 30 points higher than the members of the minimal treatment control group), and were indistinguishable from their non-autistic peers. This finding was so dramatic that Lovaas went so far as to call these children “recovered.” Those who had not “recovered” by first grade continued in intensive treatment for total of six years. At the 15-year mark, children who had made gains held steady, while their counterparts “fared poorly.” Only one minimal treatment subject performed normally in first grade; all the others were assigned to separate special education classes for aphasic, autistic, and retarded children, an outcome that Lovaas implied was inferior. Both full recovery and progress were directly attributable to intensive treatment, Lovaas concluded. Without it, “such children will continue to manifest similar severe psychological handicaps later in life.”

The report astonished readers and elicited criticism alongside excitement. Eric Schopler called the approach “strictly off the wall.” He suggested that the subjects were not representative of autistic children, nor were their parents, since they willingly turned their family lives over to full-time treatment. He pointed out that Lovaas had offered no data from schools. No teachers had confirmed that the nine autistic children were indistinguishable from other first-graders. There was simply no precedent in the research or clinical literature for so many children “recovering” from autism.

The mixed reviews reflected polarized views of the behavioral approach that Lovaas championed. Until the end of his career, Lovaas insisted that intensive behavioral interventions did more practical good for autistic children and their families than other approaches and he lamented the slowness of their adoption. But he also admitted that he had learned from his mistakes. Working with autistic children was very hard and the cost of effective intervention, in both time and money, was exorbitant. Lovaas also came to appreciate that imitating language did not help in all other areas of learning, as he had hoped. Finally, even very intensive behavioral training often yielded learning that was limited to very specific situations, did not generalize to others, and might not be sustained for long periods of time.

The studies that Lovaas conducted at UCLA presented controversial moments in the history of autism research and practice. Others have included sharply divided opinions about facilitated communication and autism’s link to early childhood vaccines, not to mention contested diagnostic criteria for autism and questions about whether its incidence is actually on the rise. Applied Behavior Analysis, based on the principles that Lovaas defended, has become a growth industry in communities all over the United States, inspiring zealous early intervention efforts in schools, clinics, and families. Applied Behavior Analysis remains contested because of its enormous expense and grueling demands on parents and professionals, which make it inaccessible to many families. But its basic approach is widely accepted, suggesting how approaches once considered radical have become mainstream.