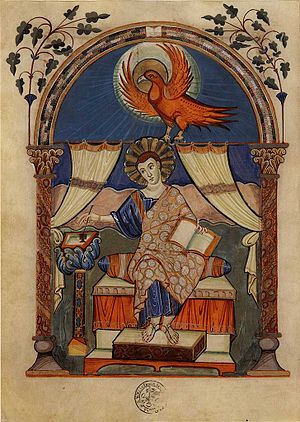

The Codex aureus of Lorsch was made in one of Aachen's palace workshops around 810 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

¶§∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞§¶

What is the aesthetic of our time?

In what ways do practices, ideas, narratives, or ideologies associated with this aesthetic depend on transmediations?

¶§∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞§¶

In your comment, include any subquestions/extensions/responses that the above questions push you toward. Address Module 3 reading/viewing assignments as relevant, and point us toward any other resources or examples that you may find (be sure to add these to the Diigo group as well!).

Comments due by midnight on Monday, Nov. 4.

And some shots of our bumper sticker remixes from last class session:

According to the article I posted below, nearly 40% of kids use iPads before they can speak. That is the aesthetic of the next generation– the bright flat screen, sleek, uncluttered, organization and research done for you aesthetic of life. Or, as the site says, “a curated, mediated, postmodern experience.” It will be interesting in 20 years to see what these babies using iPads have to say about technology. I’m both deeply concerned about what this means in the context of child development and parenting strategies and in awe at what has changed in the past twenty-some years. My “passive” baby time was chewing on straws and my “active” baby time was reacting to real live people talking to me.

The aesthetic of my time, right now, especially in the context of technology, is one of escape. We go to movie theatres, nighttime art galas, and play video games to be invested in what is happening around us without having to interact. Often times, it is the desensitizing impossibilities we witness, real or imagined, that feed our addictions to these vices. I talk about these things darkly because I see them for what they are—inherently powerful, for better or worse.

These engagement activities are, however, choices we consciously make at one point before they become as Becker might say, “habitual, embodied in physical objects and thus permanent.” I feel though, that the choices one makes about engaging in an activity or not is based largely on access. Fine arts technologies, such as photography, can actually serve this purpose very well. Photographs, which are in physicality objects and memoirs, can also be digital visions into places otherwise unknown by thousands or even millions of people. It can record people we will never meet. It can “make special” the unknown, the forgotten and the impossibly beautiful. Video games may have this same accessible nature. They are linked to intriguing environments, created by visions and sometimes, based on notions of universality.

I remember the satisfaction playing the The Sims gave me. I remember feeling intelligent, clever, invested in my Sims’ lives and ultimately, if my characters were having difficulties, I felt somehow responsible for their problems. But they were never real. I could never truly interact with them. They were art, but they were not accessible in the way I generally understand the arts.

Larry Lessig might have asked about photography or perhaps less accessible fine arts what he asks about Transmedia—should art be made to be shared? He seems to believe that technology is in some way necessary to create and that embracing all the avenues available to us is our right. Where though, is the line drawn? To what extent should original, special works of art be given freely to others? I believe that art is inherently about sharing and building community, but I’m uncomfortable with my work being appropriated without due credit given to me.

Here’s my two overarching questions in answer to this week’s topic questions:

Are video games worthy of being included in a “fine art” context or are they of an art all their own?

And…

Is art meant to be shared? If not shared, is the art’s creator being selfish and is that OK?

Article: http://nymag.com/thecut/2013/10/40-percent-kids-use-ipads-before-speaking.html

One of the readings talked about why artists make the decisions that they do within their artwork. I related very well to this analysis of thinking when I make my own artwork; a lot of my work is a balance of aesthetics and “looking good” and also what the image intentionally (and unintentionally) means. “Reliable vagueness” was a combination of words that jumped out at me on page 200 in Art Worlds. Trying to explain something that is sort of “undefinable” to terms of understanding is really the heart of the matter of art. Editing can be helpful in a sense, that with the idea of editing, one can make an artwork more comprehensible or more lucid toward the viewer. In many ways, editing depends on transmedia, on comparative artworks or ideas begotten form transmedia sources; the need to tailor to a certain market, a market that we know and recognize because of this mix of media sources. This sort of transmedia-editing process can be explored on different levels and in other settings; take billboards or window displays- each can be tailored to what the advertising firm wants. And to figure out how to tailor to the needs and wants, it is important to see what your competitors are doing, and that takes viewing multimedia. Also, the principles talked about in Art Worlds, namely self-evaluation of the product or piece of art, the ‘imagined responses of others’ help to sway what to do next.

We live in a world of fast and critical thinkers and that is how we have to adapt our thinking and practices. The aesthetic of our time is having access to technology. Our free time is spent online or in front of some screen. That is why it is so easy for artists (or anyone) to see something they like, google it, obtain the info, and use it for their own purposes. Communication and information are instant, and everything is quickened.

I loved GOOD COPY BAD COPY. I have listened to Girl Talk for many years, and copyright issues jump in my mind every time I listen to his compilations. It makes me think of early Japanese paintings and how aspiring artists would physically copy a Master painter to learn the techniques. Copyright issues I understand, but we all copy the things we see. The subconscious and conscious picks up on the visual mementos of society, and thus it is incorporated into a person’s interests, and onto a page. Plagiarism is not acceptable to be sure, but remixing? There the line gets blurry. This topic brings to the forefront so much of what culture surrounds itself with in this modern environment, most especially through transmedia, as it connects so much of the world together. Girl Talk is a unique mix of music to and I personally get a lot out of his compilations. So if we think in terms of, say, borrowing or using printed material as a tool, are two-dimensional collages infringing on the used artists or writers? What about the idea? If you interpret someone else’s idea, does that count as abusing copyright laws?

It was curious watching the documentaries on Girl Talk and taking note of the dates they were made in, 2007 and 2008 respectively. In the six to five year span since those documentaries were made the concurrence of the aesthetic of sampling beats and their distribution methods have changed drastically. As well modernly, these entities are much more widely accepted and even in some cases celebrated. An example of this is the onslaught of Dubstep and the aesthetics of sampling beats and rhythms. The genre of Dubstep revolves around the ideology of altering the narrative of samples just enough so that listeners and creator can negate the feeling of “stealing” and replace it with nostalgia for a song remastered into a contemporary rump shaker. The fact that Dubstep creators like DeadMau5 and Skrillex whose work is very much dependent on transmedia means of distribution, both legal and illegal, and apportion of others work, have been invited to and nominated for Grammys means that somewhere along the line of record executive and listener the fear of copyright and content creation became no longer as black and white or even as controversial as it was in the past. I think this is in part due to a cultural desensitization to the experience of waiting for a cultivated piece of work. Participants now want music instantly and this is supported by the accessibility transmediation lends. When music is given instantly in forms like Dubstep there is no physicality to looking at an album with listed makers or contributors. It is also hard to place value on something that is so easily consumed and given away as music can be. I think the Anti-Piracy act in the music industry and artists battle to take ownership of the aesthetics in which people experience their content through the high design of packaging is an attempt to combat this. Artists realize that through the distribution and commodification of their work through transmedia practices digital degradation has occurred. Every time a mp3 is downloaded transferred and shared through P2P groups the quality of the experience and value of their work is weakened. Becker’s chapter would argue that this instead strengthens the work as roles of participant, narrator and creator help the experience take on new forms and gain value based on the aesthetic ideology that not just one person makes the final work, all those involved in the process up until the final stage creates the works value.

So who owns the creative material, the artist or editor? The implication of editing the realities set forth by the originators is the common thread amongst all the examples this week and is how our times are redefining the factors we associate with aesthetics. Aesthetics for our times instead of becoming a definable structure to compare and contrast objects or taste is forming into an exercise of construction. Take for instance the Organization for Transformative Works which sources all of their writings from already authored story lines. These works call upon practices of readership to construct relationships and emotional bonds in new narratives beyond that of the original author. Or for instance Billboard Liberation, who alter the original advertisement experience and construct a challenge for the viewer to see beyond the original content. Or even the fan video Stacey constructed in the Jenkins article that was a construction of her emotional response to her favorite films and shows. Is the idea of ownership over an appropriated experience the seeding idea for what our generations aesthetics are? All of these forms of aesthetic I discussed depend on transmediations for the sense of instant gratification. Most of the examples given in this module were hosted on a platform that allows instant accessibility and personalization. This personalization allows for practice of ownership of experience.

In conclusion I would say the aesthetics of our time are: instantness, ownership of experience and blurred reality. All of these listed aesthetics are results of an art culture who values self creation and personalization over any other formal interstices of content ownership that past art worlds hold.

(Not sure if this uploaded…. my internet died)

The music industry gets a lot of attention in terms of copyright issues because mainstream music is so prevalent. There have been famous cases, like “Folsom Prison Blues” and “Crescent City Blues”, but then there are artists who use other artists’ work to create something new. Apart from Girl Talk, there’s Weird Al, who has been parodying popular songs for decades under fair use (which I love). Honestly, I don’t see a problem with that. I think one of the problems is that people become inspired by what they see and what they hear. Obviously with artists like Girl Talk, it’s more than an inspiration; it’s a foundation, which makes the entire situation more complicated.

Another way original art is drawn upon, of course, is through fan art, which is what my Field Guide is about. Fan art, including fanfiction, is a creative outlet. There are websites dedicated to fanfiction that are totally free, which allows it to remain in fair use. A few years ago, however, there was a case with the author of a book called The Harry Potter Lexicon. The book began as a website that compiled facts and information relating to the Harry Potter book series, but when the author published the information in book form, he was sued by JK Rowling and Warner Bros. for being too similar to something Rowling had stated she intended to publish. I find this point particularly interesting because the website survived and was never questioned, but since he would be making money off of the encyclopedia, he was sued.

There’s a very thin line between what is acceptable, which I think ties into the aesthetic of our time. I think we see what we like and we imitate it, or try to recreate it, whether it’s through music, visual art, or literature. We gravitate toward trends and we apply them to whatever we want to create. That’s not so different from what has happened in the past, but it’s much easier to take something directly from the source and make something new out of it.

A few of my favorite anti-copyRight videos:

UK Electronic Music Producer: Pogo

Muppet Mash: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwvflO3QKrI&feature=c4-overview-vl&list=PLupdJjxWWYR7Wp-GWD21Xpx_mSlfRNNch

Alice: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pAwR6w2TgxY (Please show this one in class! It is so good, and familiar!)

Street Artist: Muto:

Combo: http://vimeo.com/6555161

Blu: http://vimeo.com/993998

UK Electronic Music Producer: Cyriak:

Cycles: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0Xa4bHcJu8&feature=c4-overview-vl&list=PL81280E14A07C995D

cows & cows & cows: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FavUpD_IjVY&feature=c4-overview-vl&list=PL81280E14A07C995D

After finishing the Becker article, I could not help but think that open source file sharing, the internet, street art, contemporary art, and electronic music are shattering the traditional concepts of editing. After watching part of the Girl Talk documentary, I was inspired to curate a few of my favorite anti-copyRight transmedia resources that I would love to share with the class, particularly, Alice, by Pogo, because it is so lovely, very familiar, and gives the obligatory finger to the Disney corporation. An aspect of the Becker article that I have continued to consider is the relationship of abstract/contemporary art and the audience. There are many contemporary artists who create pieces that require a fair bit of explanation and attached narrative; the casual audience may not every known how to observe or participate in what they are witnessing due to the inherent strangeness and novelty of the piece. On the other side of the coin, easily digestible pop-art (such as Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” http://jssgallery.org/other_artists/andy_warhol/campbells.jpg) require almost no explanation from the artist, because the object depicted is entirely conventional and common place. In Collections Care today, we were discussing copy write laws and the Warhol foundation/museum was mentioned a few times; the Warhol Foundation are notoriously ruthless when it comes to maintaining copy write to Warhol’s pieces, but, I must ask: did Warhol receive permission and license from Campbell’s to produce his painting? Further, did he receive permission and license from the artist who designed the Campbell’s can? These questions are a bit ludicrous, but, if Disney sued Pogo, I would consider their litigation similarly ludicrous. In this day, when the internet makes, virtually, any movie, album, book, or image available it is difficult to be attached (or overly concerned) with the antiquated notion of copy write, at least, in my humble opinion, but I am steeped in a mashed-up celebratory culture that strives for innovation and novelty.

Aesthetics. For starters, it has always been a very difficult term to work with in English because I feel like it has very different use than its parallel word in Spanish. So I looked it up and the dictionary defines aesthetics as the “level of beauty” and the “principle of taste or style adopted by a particular person, group, or culture”. The definition of this term combined with what Becker writes about makes me think of a very particular subject that we deal with in music and that is very specific to this performing art.

By assumption, all of us that dare to call ourselves classical musicians play mostly music that was composed, a VERY LONG TIME AGO. For whatever reason, this classification goes beyond just playing music from the classical period and embraces pretty much all works that need of classical instrumental training to reproduce. For instance, we are continuously performing pieces of music that were written two centuries ago in the most modernized instruments possible. So, many questions arise from this issue: is it correct to perform a piece that was composed for a much less developed instrument with our current instruments since it obviously wasn’t intent to sound that way? Many argue that if Baroque composers were able to had at their disposal the instruments we have now, they’d love to hear their music played by them.

On the other side of the spectrum rely things like the opening bassoon solo of the Rite of Spring. Stravinsky wrote it in the highest, most difficult range of the instrument, barely explored at the time, in a meter and key signature that made it extremely difficult to perform. But Stravinsky made it like that because he wanted it to sound difficult. Nowadays, whenever this solo is played, it is expected for it to have a lyrical nature, smooth sound, and clear rhythm. People want it to sound easy.

Is there a right or wrong way to interpret these issues? Are we violating the work of the composer? The answer varies from person to person, but one thing is for certain: we’ll always try to make thing sound the best way possible.

I believe the aesthetic of our time lies somewhere in between the factual knowledge of historic preservation and the provoking suggestiveness of Contemporary Art practices. Call me a loner, call me cynical, or just plain call me out, but I feel as if the aesthetic of our time has become disposable. With the demand for instant gratification and the onslaught of advertisements, both in print and online, people have more visuals to sift through in their day-to-day than ever before. Research is more convenient, but credibility is more questionable. Appropriation has become more acceptable, but originality is often sacrificed. As aesthetic translates across platforms, it can lose integrity and gain new meaning.

In the reading, Becker opens up about the process of editing with this quote, “We can see how, in fact, it is not unreasonable to say that it is the art world, rather than the individual artist, which makes the work” (Becker, p. 194). His statement mirrors the ancient African Proverb “It takes a village to raise a child”; both of these claims give credit to the reality that art and people are clearly products of their environment. I agree with Becker that no matter how original the thoughts and actions of an artist are said to be they still “make choices in reference to the organization they work in” (Becker, p.199). It is impossible for every choice of the artist to exist independently and without previous influence. The lingo found within an art world also reinforces this idea. For example, graffiti artists are quick to adopt slang and often rely on this genre specific terminology to explain their motives, define their inspirations, and justify their reasoning for creation of “pieces”, “throw-ups” and “bombs”. Graffiti artists often become so engrossed in the art world that explaining their work to outsiders (those unfamiliar with the art form) without the use of slang may present a challenge. When it comes to expression across transmedia platforms, narratives of oral history depend on the flow of natural dialogue.

In discussing the profound effects of editorial moments, Becker suggests “It is crucial that people act with the anticipated reactions of others in mind” and he goes on to claim that artists create work in anticipation of how their audiences will respond emotionally and cognitively (Becker, p. 200). This artistic process would lend itself well to the creation of what I like to call an audience statement. In juxtaposition to the artist statement, an artist would produce an audience statement to explain how it is he/she would expect the audience to react to the work produced. As Becker describes, “They [the artists] take the point of view of any or all of the other people involved in the network of cooperative links through which the work will be realized” and then make the conscious decision to modify or not modify it to fit (or not fit) within the realm of other works (Becker, p. 201). Becker’s declaration that “What audiences choose to respond to affects the work as much as do the choices of artists and support personnel” suggests the validity for creating an audience statement (Becker, p. 214).

Both visual artists and performance artists are influenced by similar factors such as time and constraints and limited resources (Becker, p. 202) but what I find intriguing are the differences that attribute to the creation of a work of visual art versus a performance art piece. Would you agree that visual artists are more inclined to produce works of art for personal enjoyment rather than for consumption by an audience than performance artists would be? Becker implies that artists must sometimes violate the standards of an art world in order to be considered innovative, they “must unlearn the conventionally right way of doing things” (Becker, p. 204). Artistic revolution depends on aesthetic to outline what it is that has been accepted by an audience; without this aesthetic to refer to, the artist would not be able to conceptualize new and different ideas.

Lastly, the article suggests that art dies because it either becomes a victim of neglect or political sabotage, but it fails to address the destruction of art by natural disasters (a contributing factor beyond human control). As I was conducting research for my transmedia field guide project, I came across an interesting organization, the Salvage Art Institute (http://salvageartinstitute.org/). This group is dedicated to articulating the condition of once valuable works of art suffering from irreparable damage and removal from art market circulation. The Salvage Art Institute addresses the aesthetics of our time by considering an artwork’s “total loss” in value with the legalities of insurance-claims in mind.

The aesthetic of our time has been condensed from 15 minutes of fame to 15 seconds. The next overnight internet sensation holds the key to success. It’s no longer about how you do it, but who does it first. Aesthetic has and always will find a home in human emotion. The aesthetic of today presents heightened emotion – it’s untethered, it’s raw, it’s provocative. Girl Talk is shameless, Kutiman’s Youtube channel delivers expression rooted in the sensitivities of real people, and the Gregory Brothers AutoTune the News series gives us a dose of ridiculous anecdotes. The Billboard Liberation Front reminds me of the work of Graffiti Research Lab; their art techniques dance the line between freedom of speech and vandalism. The work of these artists reminds us, the public, that we are still entitled to have a say…we only need to figure out the right way to say it. Check out GRL’s Light Criticism project at http://antiadvertisingagency.com/project/light-criticism/

The aesthetic of our time is somewhat paradoxical in that on one side of the spectrum, advertisements, media, and culture are open, moving at a high speed, quickly changing, brilliantly colored, provocative, loud, diverse, and malleable as they filter through individual experiences and manipulations. There are massive amounts of information fighting for our attention, like Times Square, but digitized for the global audience/participants. On the other end of the spectrum, major motion pictures are longer and there are longer story arcs in television shows spanning not just one season but multiple seasons. However, within these genres, each episode or film switches scenes frenetically and the plots tend to move quickly. Our society has “shortened attention spans,” not only with the media that we are inundated with, but also regarding our contributions to the dialogue via transmedia.

For example:

• We can only tweet 140 (is it?) characters.

• POTUS, FLOTUS, SCOTUS

• Does anyone really read Facebook status updates that are longer than two lines and how long do updates really stay in the news feed?

• Campaigns and organizations that send out mass mailings know they have their recipients’ attention from the time they pick up their mail to the time they throw it away, which is a maximum of about 30 seconds.

• Pop Music fits into a nice little framework: verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus = approximately 3 minutes.

I heard Speight Jenkins, General Director of Seattle Opera, cite the competition of transmedia platforms as some of the reasons why live theater, opera, and symphonies are losing audiences. He said we are asking people to sit in seats for two hours with only two ten minute breaks and really focus on something for a long period of time. I think this is true, but I also think that it is the lack of audience involvement in the creative process that is causing audiences to shrink. The fourth wall is too powerful. To the contrary, in Rip, Girl Talk was incredibly audience oriented to the point that there was no audience and he didn’t perform a show so much as create a livable music experience. This involvement creates excitement and investment for the participants and builds its own culture.

I think people are really hungry for information and engagement because we are social creatures, which results in a vastly creative cultural story. That is why the Internet and transmedia platforms are so successful – each person is empowered in making individual contributions to the world and changing because of what they absorb. This weakens the traditional institutions that have controlled information such as the major news and entertainment companies, and gives real grass roots organizations a chance for existence as they access and create networks for whatever purpose they may have.

The generation that has grown up and is growing up with transmedia as an integrated part of their lives would not function without it should it be taken away because it is their source of cultural engagement and aids them in creating their communities. Our society in general would not function without it because we are so acclimated to sharing. And, yet, despite the freedom we feel we have, there are laws that allow for the President of the US to flip the switch and shutdown the Internet should any situation be considered a threat. We’re building a shared, virtual culture that doesn’t exist in hard copy and can disappear instantaneously. So, what do we do when it disappears? Has the culture died as Becker says art works die when they can’t be seen?

In my view, the aesthetic of our time is lost in its own identity (or lack thereof), where we (like generations before us) borrow and steal concepts and traits from bygone eras to “reproduce” or “create” something that is not original or imaginary. There is an old saying about music that after four notes of composition, you aren’t composing anymore, you’re stealing. Everything that has been written already exists in some form or another. We adapt these models and structures and label them as new and emerging, even going so far as to create a jargon to pay homage to these ideas (old-school, vintage, etc.) or new (trending, etc.) but we aren’t, in actuality, creating new works or pieces, we are reinterpreting them. Is this wrong? Certainly not. But when we attach a label like aesthetics, my mind associates a qualitative definition within these values and makes me want to judge them based on the source material. Is it better? More often than not, no (my opinion). There is a reason we define classics in the arts as such; they embody a timelessness and a sense of unbridled originality (The Beatles, George Seurat, Homer). But remixing or sampling a hip hop hook or painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa does not automatically entitle you to artist status.

I recently read an article about the Benjamin Palmer Company spending $3,500 on a piece that was nothing more than an interactive website of geometric shapes. Work of art? Perhaps. But algorithms can create these same shapes with minimal human efforts. Is digital media truly offering us a new way to creatively express ourselves as artists or merely making it easier to fabricate others’ efforts in the name of something groundbreaking and unique? Are aesthetics taking a backseat to bandwagon mentality of Facebook “likes” or are we honestly seeing creativity at its best given the circumstances?

Becker talks about art works as the product of art worlds as opposed to just the individual artist. He uses the example of editors influencing pieces of work in major ways and the impact of an audience’s perceived response on an artist’s decision making process. He depicts art as the product of a series of choices. The work of remix artists like Girl Talk can be seen as the product of an entire art world as opposed to an individual artist. While each Girl Talk song starts out as a number of separate individual songs by a number of artists, Gregg Michael Gillis (otherwise known as Girl Talk) combines the original songs in a new and innovative way. This practice of sampling and remixing other artists work fuels debate about intellectual property and copyright issues.

The practice of taking previous art works and using new technology to manipulate them into new pieces of art has become the aesthetic of our time. Mash-ups are all over the internet and songs on the radio frequently feature refrains or beats from previous records. While the practice of artists borrowing from other artists (Shakespeare comes to mind) is not new, it has become more prominent and more problematic in the modern day. This new art form would not be possible without the proliferation of remixing technology that has come about over the last twenty years. Also, without the Internet mash-up artists would likely not have an audience with which to share their product.

While I agree that current copyright laws are overly prohibitive and impractical in a day and age where the means of downloading and remixing are so readily available, I wonder what should replace the current system. The idea of individuals paying a flat rate for unlimited access is interesting, but it would be difficult to create buy-in for such an idea as long as there were still methods for accessing music for free. Also, I wonder what sort of impact a shift in copyright law would have on artists. Obviously, the current situation is far from ideal, with much of the profits going to record companies instead of artists. I found the culture of media consumption in places like Nigeria and Brazil to be interesting alternatives to our own restrictive culture, however I feel like in those systems the artists risk not being compensated. What sort of system could ensure that artists are paid what they deserve and individuals are free to sample and build upon the work of other artists? Is such a system even possible?

Having lived in Denver during the 2011 NFL season, this is my absolute favorite mash-up. It is super catchy and annoying so beware.

Becker talks about art works as the product of art worlds as opposed to just the individual artist. He uses the example of editors influencing pieces of work in major ways and the impact of an audience’s perceived response on an artist’s decision making process. He depicts art as the product of a series of choices. The work of remix artists like Girl Talk can be seen as the product of an entire art world as opposed to an individual artist. While each Girl Talk song starts out as a number of separate individual songs by a number of artists, Gregg Michael Gillis (otherwise known as Girl Talk) combines the original songs in a new and innovative way. This practice of sampling and remixing other artists work fuels debate about intellectual property and copyright issues.

The practice of taking previous art works and using new technology to manipulate them into new pieces of art has become the aesthetic of our time. Mash-ups are all over the internet and songs on the radio frequently feature refrains or beats from previous records. While the practice of artists borrowing from other artists (Shakespeare comes to mind) is not new, it has become more prominent and more problematic in the modern day. This new art form would not be possible without the proliferation of remixing technology that has come about over the last twenty years. Also, without the Internet mash-up artists would likely not have an audience with which to share their product.

While I agree that current copyright laws are overly prohibitive and impractical in a day and age where the means of downloading and remixing are so readily available, I wonder what should replace the current system. The idea of individuals paying a flat rate for unlimited access is interesting, but it would be difficult to create buy-in for such an idea as long as there were still methods for accessing music for free. Also, I wonder what sort of impact a shift in copyright law would have on artists. Obviously, the current situation is far from ideal, with much of the profits going to record companies instead of artists. I found the culture of media consumption in places like Nigeria and Brazil to be interesting alternatives to our own restrictive culture, however I feel like in those systems the artists risk not being compensated. What sort of system could ensure that artists are paid what they deserve and individuals are free to sample and build upon the work of other artists? Is such a system even possible?

Having lived in Denver during the 2011 NFL season, this is my absolute favorite mash-up. It is super catchy and annoying so beware.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zMK9FKMG3Nc

In “Editing,” Becker discusses how the choices of the artist and the collection of contributors within the art world impact the artwork itself. He emphasizes that these choices of editing and alterations “affect art works beyond the life of the work’s original maker” (p. 198). When reviewing that statement, I immediately think of the controversy that surrounded the Barnes Foundation (http://www.barnesfoundation.org and http://www.ifcfilms.com/films/the-art-of-the-steal). It revolved around an entire collection of Post-Impressionist and early Modern paintings that was removed from the original site of the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania to Philadelphia. Although this situation does not include direct choices made to the content of the artwork, I think the changes to the context and environment surrounding the artwork can have an undeniable impact as well. The transfer of artwork became a concern as it challenged the will of Albert C. Barnes to retain the collection in the original location, which cultivated an educational grounding through the appreciation of these pieces in a small environment. This intent, as some may argue, was lost when these paintings were relocated to a museum that served the masses. Given this situation, how does a piece of artwork, including its context, retain the same intention of the artist when perspectives of or means to learning and accessibility change? Can the intention or purpose of artwork be manifested in multiple ways without losing its integrity?

In some respects, I think these questions relate to the aesthetic of our times. They highlight the scope of reaching to the masses and the multitude of audiences in that the ability to view and appreciate artwork is not confined to a certain group of individuals. Art worlds, including museums, community arts organizations, libraries, performance centers, etc., rely on digital representations of art to increase their accessibility, which are conducted through photographs, video clips, websites, etc. Though the visibility of artwork increases through these transmediations, how much of these are viable sources for thorough education, learning, and growing the appreciation for art?

In our generation, the learning media and method change the aesthetics of our time! Before, you learned or acquired knowledge mostly from books and classrooms. In the art education, you have to go through a specific training process to become a painter. However, with the advancement of technology, the time and the manner of learning changed. For example, there is a Youtube video that elaborates how to draw a water drop step by step. If you want to learn how to draw it, you only need to access to the videos and figure out some basic principles of drawing.

Because the process of absorbing a knowledge change, the aesthetic angle has changed. Previously, people needed to be trained to appreciate the aesthetics of art. Becker mentions in the chapter (pp.217)”audiences can both learn experience new elements and forget how to experience old elements of a work, as we have lost the ability to respond directly to the religious and geometric elements of fifteenth-century Italian painting without special training”。However, nowadays, we can appreciate art work via the transmedia easily. Even when at home seating in front of your computer, you can see the art work thought museum’s Virtual Tour. For example, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. provides a 360 degree virtual tour online. You can explore the whole museum through the internet; the distance is no longer the barrier of learning art.

As the mater of fact, in our generation, excessive information has permeated our lives. Aesthetics becomes very subjective and personal. Moreover, you can be a re-creator if you are interesting in the art piece you like, but this change also brought up the problems of copyright and piracy. In the good copy and bad copy video, the grey album, a mash-up album produced by DJ Danger Mouse, changes people’s perceptions about music and what you can do with music. Also, the copyright issue appeared in the music industry. With such questions who owns what? What is the purpose of copyright?

In my point of view, transmedias dominate the aesthetic of our generation and creativity is now online. If you possess a computer, you can start using sounds and imagines to express opinions about politics or culture. Remix, recreation and parody become trend on internet. Access to the internet seems like the painting brush to our generation.

how to draw a water drop:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82e3Osa83_w

One of the aesthetics of our time is collectivity. In several examples Becker discusses the collective decision making of artists in creating an art world. He states, “Artists similarly take the imagined responses of others, learned through their experience in an art world, into account when they complete a work” (202). He discusses the idea that art worlds, rather than artists, are what make works of art (198). I believe that there is a renewed emphasis placed on collectivity and collaboration in the creative world. And it is the use of transmedia that perfectly illustrates this idea. Transmedia itself is a collaboration, a collective of several points of reference. Transmedia is quickly becoming the aesthetic of our time as it represents a certain coming together of the digital and the real, a collectivity of resources.

In a panel discussion, the term “New Aesthetic” was discussed at SXSW conference 2012. This term refers to the increasing appearance of the visual language of digital technology and the Internet in the physical world, and the blending of virtual and physical. The panel introduction stated; “Slowly, but increasingly definitively, our technologies and our devices are learning to see, to hear, to place themselves in the world. Phones know their location by GPS. Financial algorithms read the news and feed that knowledge back into the market. Everything has a camera in it. We are becoming acquainted with new ways of seeing: the Gods-eye view of satellites, the Kinect’s inside-out sense of the living room, the elevated car-sight of Google Street View, the facial obsessions of CCTV. As a result, these new styles and senses recur in our art, our designs, and our products”. There seems to be an artistic blurring between the digital and the real.

As the digital world transforms, the artistic world pushes against convention and continues to be on the precipice of the “new”. Art worlds are embracing all that the digital world possesses in order to move forward. Sometimes this creates friction. The idea of copyrights and limitations due to artists contracts are a matter to be considered. How far is too far when dealing with the accessibility of the digital world? Just because there exists access, does that mean that everything is a given and a free-for-all if it suits one’s purpose? Conventions of the past provided boundaries which artists remained inside. Although conventions can be boring and restrictive, is it always best to ignore them completely when trying to create a sense of unpredictability and newness in the work? With the explosion of resources at our fingertips and not much regulation of them, when do we draw the line?

article: http://schedule.sxsw.com/2012/events/event_IAP11102

Self-documentation is a major emergent trend in informal cultural production. The quotidian is distributed as a social performance. People “check in,” post photographs, schedules, product reviews and video responses. The aggregate–the documented self–is a cultural form. Typically, the documented self is an amalgam of editorial decisions in response to the aesthetic judgments of the performer’s lived experience. However, a few artists have used the documented self as an formal/intentional work. The following examples highlight the transmediation of lived/performed experience.

Nicholas Felton produces Feltron Annual Reports that provide infographic data about his activities during a given year. The Feltron Annual Reports offer humanistic approach to the quantified self.

(Felton’s Website: http://feltron.com/ )

(Rhizome Interview w/ Felton: http://rhizome.org/editorial/2011/jun/1/storytelling-interview-nicholas-felton/ )

Hasan Elahi’s work often uses the documented self as a means of addressing surveillance, citizenship, migration, transport, borders and frontiers.

(Elahi’s website: http://elahi.umd.edu/ )

(Elahi’s TEDTalk: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wAdwurHhv-I )

Module 3 Reading Response

Becker describes the process of editing as a series of choices made by the artist and those around him. He states, “think of an artwork taking the form it does at a particular moment because of the choices, small and large, made by artists and others up to that point.” These choices are what “shape the work” (Becker, 194). Essentially, editing is inherent in the act of creation. This discussion reminded me of one of my favorite quotes by Thomas Merton, “We must make the choices that enable us to fulfill the deepest capacities of our real selves.” I have frequently thought of life itself as a form of art. If we look at our lives as this great masterpiece in progress, each decision we make, no matter how mundane or drastic, is akin to an artist putting elements in place to create a meaningful and beautiful composition. Considering this, life becomes exhilarating and empowering. Ultimately, we are all editors of our own life’s work.

As Becker extensively explores the world of editing, he once again stresses the idea that art does not happen in isolation, and artists, even the most lonesome ones, never work alone. I think this concept of collaboration fuels the aesthetic of our time. In a world where everything has been done (a thousand times over), how can one (or many) create an original work? The answer lies right under our noses: appropriation. As seen in Kutiman’s music videos, Auto-tune the News, and compilations by various DJs, including Girl Talk, remixing is the ultimate form of editing: taking works by others, deliberately choosing bits and pieces to mix and match until an entirely new (and original, never-been-done-before) composition emerges. With the widespread availability of new technologies, these kinds of remixed works, are not only inevitable, but unstoppable. Almost anyone with a computer and a little bit of time can “get creative” and start remixing on their own. Suddenly, those previously considered amateurs are able to self-publish and form reputations for themselves independent of established publishers, record labels, or agents. We are seeing a shift in the network of “supporting personnel” from middle-men giants to a web of everyday people, including other ‘amateur’ artists, musicians, performers, videographers, programmers, entrepreneurs, and more, who all simultaneously invent, produce, share, and feed a complex entanglement of creation and recreation.

Instant gratification has a lot to do with what the aesthetic of our time is. We want it now, we want it fast, and then we get bored of it and then throw it away. Social media makes sharing our art or ideas very easy. When you throw something up on facebook or instagram it is distributed quickly and easily to your friends and network. The internet and technology has played a big role in how aesthetic has changed over time.

Michelle made an interesting point about how some kids learn how to use iPads before they learn to speak. I have been in awe over a video I saw on youtube where a baby has an iPad set in front of him with a book/magazine app open. The baby can turn the pages of the e-book no problem. Then someone sets a real paper magazine in front of the baby and he does not know how to flip the pages. Here is a link to a similar video. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqF2gryy4Gs) I agree with Michelle and think that it is concerning to see how this will affect child development of that generation.

One question that was brought up was about video games. Are they considered art? I decided to ask my friend who is an avid gamer to see what he thought about it. Specifically I asked whether he thought playing games could be considered an art. I know very little about gaming but I do know that it is a whole other world with a social aspect and sense of community. You can connect with people from all over. There also may be an art to it. My friend responded that he thought some games have a technical aspect to them and depending on how (well) you play or your skill level it can be considered an art.

I am also interested in the issue of copyright that was brought up in both documentary videos “good copy, bad copy” and “RIP: a remix manifesto.” I think copyright laws force us to be more creative and use our own original content. I do think that Girl Talk’s music creates an interesting controversy and I’m not entirely sure where I stand. His music seems creative and original but he is using material that is not his. From watching one the videos I found out that sometimes he only borrows one note from a song and repeats it or draws it out. He rearranges and layers notes and samples to make the song his own. One of the people in the video states that even borrowing one note is an issue! This, to me, seems crazy. How can you write or create anything without “copying” some portion of an artist’s work that influences you or came before you. As an amateur writer, I find it very hard to create poems, lyrics, or songs without being influenced by other famous works. Inevitably, even unintentionally we will create songs that have at least one note, one chord, or one progression that is “copied” from another artists. So where do we draw the line?