Johnpaul Jones, FAIA: “Seeing the Things In Between”

The 2011 Pietro Belluschi Distinguished Visiting Professor in Architectural Design is Johnpaul Jones, FAIA, of Jones & Jones Architects, Landscape Architects, and Planners, Seattle, Washington. In the fall of 2011 and as the 2011 Pietro Belluschi Distinguished Visiting Professor, Johnpaul Jones presented two lectures at the University of Oregon for the School of Architecture and Allied Arts Department of Architecture: “The Frog Does Not Drink Up the Pond in Which It Lives, “ October, 2011 in Eugene; and “Times Change but Principles Don’t,” November, 2011 in Portland. Among the many attendees at the lecture in Portland at the UO in the White Stag Block were Pietro Belluschi’s two sons, Peter Belluschi and Anthony Belluschi.

Jones has a distinguished 40-year career as an architect and founding partner of the Seattle-based firm, Jones & Jones Architects, Landscape Architects, and Planners. His design philosophy emerged from his Choctaw-Cherokee ancestors and connects his work to the natural, animal, spirit and human worlds. His designs have won wide-spread acclaim for their reverence for the earth, for paying deep respect to regional architectural traditions and Native landscapes, and for heightening understanding of indigenous peoples and cultures of America.

What follows is a post on his Portland lecture, “Times Change but Principles Don’t.”

Johnpaul Jones is internationally lauded as an architect of both structure and landscape in Native, indigenously-inspired design projects. Jones’ projects take a multidisciplinary approach swirling together symbolic Tribal activity, a sense of place, the natural environment, Native social customs, and religious beliefs. His projects stand as virtual cultural reconstructions and beautiful culminations of cosmological concepts and life represented in an architectural achievement. Jones’ approach is one that reaches well beyond the basic requirements of a building to incorporate Native sensibilities and aesthetics. His ability to bridge a path between the built environment and the Native universe, has allowed him to meld buildings rich with imagery, connections to the earth, and stratifications of story with reference in color, texture, and detail creating both a structure and a site that melds story and interpretation of a living, reacting, existing culture.

Johnpaul Jones began his presentation, “Times Change but Principles Don’t,” with an acknowledgement of the namesake of his distinguished professorship: Pietro Belluschi; Jones also profusely thanked both of Belluschi’s sons, Peter Belluschi and Anthony Belluschi (seated in the front row) for attending the lecture. “Your father,” Jones proclaimed addressing both the audience and Belluschi’s family, “was timeless, he had spirit.” Jones asserted that the designs of the famed Northwest architect “inspired [him] to become an architect.” Also, praising his architectural education at the University of Oregon, Jones recalled that “[UO] was the right place for [him].”

Jones, himself of Cherokee | Choctaw heritage, became involved in Native art and architecture early in his career due to his belief that one must bring new life to indigenous design and commit to taking a sort of pilgrimage to Native cultural environments thereby becoming influenced and inspired by the rich aspects of these Native traditions. He encouraged a proactive personal seeking of this heritage as a way to gain an awareness of the Native environment. This individual participation in the culture of a region would contribute to one’s understanding of distinctive forms. Once one has experienced this uniqueness of site, the subsequent built environment and landscape design will more honestly evoke Native stories and connections to all four of the worlds present in indigenous beliefs: natural, animal, spiritual and human.

The importance of these four worlds to design and structure, according to Jones, cannot be underestimated —as these elements become the formative basis of the project. Jones reflected that the natural world has the potential to effect us everywhere and needs to embrace the idea of sustainability as a constant. The natural world deals with light and the seasonal equinox and solstice patterns. Thus, in designing for a site the very initial step taken should be noting the cardinal directions, the location of the sun, and the stars in the cosmos.

Animals are of importance to a design and structure as well. Many Native stories come from the animal world. Using the inspiration of a living, breathing thing, whether a delicate frog, butterfly, bird or dragonfly to tell a story about life, existence and the fragility of living beings becomes a powerful design principal. The spirit world contains objects such as rocks, views, mountains and trees, as all things have a spirit, says Jones. Understanding or recognizing this idea of the spirit world will translate to a respect for the site and a comprehension that the land has something to tell. Equally important is the human world as in all work there is the element of the passing on of knowledge. Good design must provide opportunities to pass knowledge; and this component comes from the human world.

Using the idea of a canoe filled to the brim with elements from all four worlds: natural, animal, spiritual, and human, Jones urged architects to “listen to the client, respect the land of the site, and be aware of the bigger message.” The built environment is not just a sequence of buildings, said Jones, but stuctures that contain “life messages” and serve to act as translators of both ancient and indigenous gifts.

Jones continued by discussing several projects he has participated in: the National Museum of the American Indian, the Commons Park in Denver, Colorado, and a zoo design. In each project, Jones emphasized that importance of a diverse practice and the diversity of design but, overall, the importance of a respect for the environment and natural settings and an integration of all four worlds.

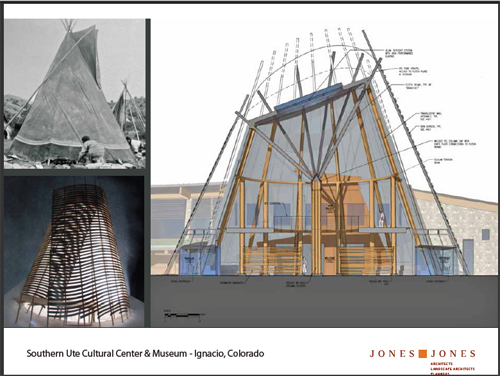

For each of his projects that involved Native tribes, Jones recounted the sequence of the work pattern. First, one must establish what is “welcome.” He urged both the writing and thinking of the idea of “welcome.” In addition to discovering this key concept of “welcome,” the architect must work with the tribe to determine the life force of the people. In his cultural museum design at the Southern UTE Cultural Center and Museum in Ignacio, Colorado, Jones spoke of the lives of the people as always spiraling outwards much like the spiraling basketry the tribe handcrafted. Jones made a connection between trying to work within these stories and integrating this concept into the ultimate design.

Discussing his work with the Mercer Slough Nature Park in Bellevue, Washington, Jones described the master plan as embracing the value of creating a place for walks and a place where people could connect with themselves. This connection space and place would serve to provide a sense of enjoyment. By integrating walkways and spaces in between the buildings, providing places to sit and see nature and the natural views of the surrounding landscape, and giving ample opportunities to appreciate the natural light though large windows in the buildings, Jones developed a way to integrate the person to the environment. In doing so, the architect provided a source for conversation about what is being seen and what one is literally surrounded by. Jones calls this “giving reasons to talk to [children] and to explain things.”

At Fort Vancouver, Jones related a project of reconnection, of a circle that connects to itself, his renowned Vancouver Land Bridge and was a key component of the Confluence Project. His design here is intended to reconnect visitors to the river and to the land; to uncover the spirit of the place and the enchantment of the history, both Native and of the Western Europeans. The effort one must make to “walk up and over and into the Fort” compels a sense of circular involvement and movement in amongst objects that seem low and unobtrusively part of the land.

Sleeping Lady Mountain Retreat and the Icicle Creek Music Center, Leavenworth, Washington, is a project of Jones’ where he let his design meander naturally and organically throughout the complex. Integrating large windows that face snowy, rocky hillsides, Jones thought to bring the outside in and use the natural surroundings to inspire the work of the musicians composing, playing, and practicing within the retreat. As Jones puts it, his arms swirling to evoke the movement and melding of nature and music: “you can see clouds moving, birds flying, and this brings the spirit of the music alive.” It is a place to create and to observe, a place where one is not separated from the natural environment that is so strikingly just outside the windows but where one can infuse creative musical composition with the stunning visual component of the dramatic landscape and moving weather systems.

Architects must be adept at designing for emotion, Jones continued. In the early 2000s, Jones was asked to design the masterplan for the Bainbridge Island Japanese-American Memorial, a monument wall to honor the Japanese Americans who were displaced during WWII. Jones created a place of quiet, a gently curving cedar wall where visitors can remember and honor their ancestors. Key to this project was working directly with the Japanese American community of the region to discover what they would feel epitomized their emotional response. The site would have to be something that recognized all diverse peoples. Jones recalled with reverence the appreciation he received from the Japanese-American community for this project.

Jones’ most recent Native project is the cultural education center in the Rocky Mountains, the Southern UTE Cultural Center and Museum, in Ignacio, Colorado. Jones spoke of how the tribal members came to him and asked for a building that would represent their “circle of life”philosophy. The tribe wanted a permanent gallery, a temporary gallery, and a native gift shop in addition to educational and administrative components and a library. The desire was to have a complex that began in a space that was clearly a Welcome Center. Jones devised a welcoming area that utilized the tribal concept of a cone, or a circle that crossed a stream and progressed under an arbor covered in a translucent material to let light glow within. Jones thought that the most important component of this project was that it feel welcoming and that it resonated with the cultural mores of the tribe. The resulting structure makes use of a great deal of colored glass (similar to the architectural designs of Pietro Belluschi, said Jones, as well as echoing the regalia of the Native tribe on this land).

As Jones brought his presentation to a close, he somberly appealed to his audience to remember: “Times Change but Principles Don’t” and commented that he felt Pietro Belluschi had understood this in his designs. “We are destroying the earth,” cautioned Jones.

Jones’ lecture reminded the audience that the times have changed, the landscape is rapidly changing, but we remain here to live together and to be creative in the pursuit of allowing this land and all the people to listen to the swaying of the leaves, the roaring of the river, the blowing of the winds, the snowcapped majesty of the mountains. The smallest frog or butterfly should be compelling enough to inspire a connection to animals and nature; the weather and the flowing of time, might evoke spiritual appreciation, and the father sitting with his child on a park bench telling her the story of the woodpeckers or the creek or the bear, should provide a reason to think about the human world and the importance of communication, conversation, and connecting with one another. Jones encouraged all to look in between things, to observe and notice that which is always present and around us.

Jones’ Portland lecture was delivered to an audience of over 150. Quiet and contemplative throughout the presentation, listeners fell into an even greater sense of attentiveness as Jones read a well-known poem by Chief Dan George:

The beauty of the trees, the softness of the air, the fragrance of the grass, speaks to me. The summit of the mountain, the thunder of the sky, the rhythm of the sea, speaks to me. The faintness of the stars, the freshness of the morning, the dew drop on the flower, speaks to me. The strength of fire, the taste of salmon, the trail of the sun, and the life that never goes away. They speak to me. And my heart soars.

“We are part of this planet,” said Jones, “It is never going to go away. So, take care of it.” Jones advised, by “listening and being respectful,” and, above all, we must all seek to “see the things in between.” Do not forget the importance of “the place, the culture, and the environment, keep bringing these up” he encouraged. When designing, “keep at it, and put people right in there.” While Jones credited his mother and grandmother for teaching him the lessons of his heritage, he also thanked his university education for developing his approach. Adopting a humanistic perspective and maintaining a design philosophy where the people-element is never forgotten or sacrificed is a principle Jones proudly says he “got from the University of Oregon.” Post-lecture, Jones was asked for his comments about this recent experience as the Belluschi Distinguished Visiting Professor and his work with the students at the University of Oregon. He commented that he tried to instill in the students the idea that “It’s not the final designs, even though that is what we are judged by, but the ‘Emerging Indigenous Gifts’ that count.” He added that he would like to “thank all of [the University] for the opportunity [it] gave [him], and look forward to continued interchange.”

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Jones’ lecture provided an education into the wisdom and unparalleled legitimacy of indigenous peoples. His ability to come into the peace of a wild, natural environment and to absorb the presence and stillness of nature by bringing that into his designs is a principle of grace and understanding. As an architect, Jones has allowed his heritage to move him and transpire into a empathetic design aesthetic. It is this multidisciplinary aesthetic that brilliantly incorporates into his architectural systems and thus adding meaning and story to the landscapes, shapes, textures, colors, patterns, rhythms, and forms of his projects.

[Note: the video of Johnpaul Jones’ Eugene lecture is available at the following location: “The Frog Does Not Drink Up the Pond In Which It Lives.“]

post sabina samiee

many heartfelt thanks to johnpaul jones for sharing his images with us for this blog.