Chicago architect and award-winning preservationist, Thomas “Gunny” Harboe, FAIA , was the inaugural keynote speaker for the George McMath Symposium on May 30, 2012 at the University of Oregon in Portland at the White Stag Block. The lecture was held in conjunction with the presentation of the George McMath Historic Preservation Award. This year’s 2012 award was presented to Portland architect, Hal Ayotte.

Harboe works with the firm of Harboe Architects in Chicago. Harboe’s lecture, “Restoring Chicago’s Icons: A Public/Private Partnership,” focused on describing Harboe’s fascination with the past, respect and passion for historic objects, and his work with some of Chicago’s most historically and architecturally relevant restoration projects. For over 20 years Harboe has played key roles in working to restore iconic structures of the Chicago cityscape, including the Rookery, the Mies van der Rohe apartments on Lake Shore Drive, and the Reliance and Marquette buildings. “Preserving our collective cultural heritage is important to society,” commented Harboe, “we need to give it a life that will extend it beyond us.”

With a lifelong interest in conservation and preservation, Harboe credits his childhood experience of living in a New Jersey Revolutionary War-era home as fostering an early affection for history and objects. It was in this historically relevant family residence that the young Harboe discovered an interest in found objects and gained an appreciation for antiques. Harboe soon turned to an education steeped in historical study, spending a year in Denmark at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen; and later earning a bachelor’s degree in history from Brown University and a master’s degree in historic preservation from Columbia. His hands-on and practical skills were cultivated further with his work as a carpenter eventually leading to a job on the team that would restore the Frank Lloyd Wright Room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Harboe has credited that MoMa experience as being “where the epiphany happened. I realized that the key decisions about what got done had already been made by somebody else: the architect.” Hence, he turned his focus to pursue a master’s in architecture from MIT.

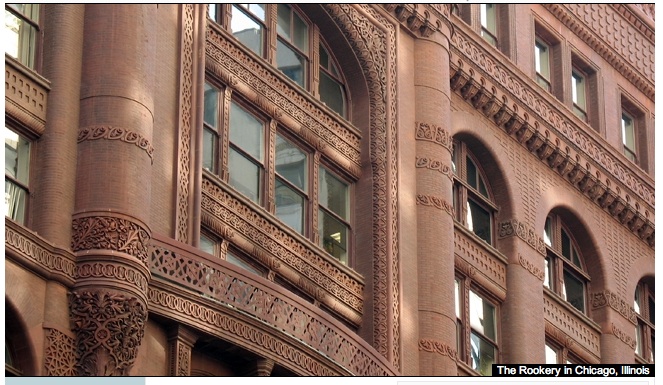

Harboe, equipped with load-bearing quantities of academic, visionary and practical experience was soon working with the Preservation Group at McClier, the architects who would be commissioned by the Baldwin Development Company to restore The Rookery. Considered the jewel in the crown of Chicago’s architectural and commercial built environment, The Rookery is a 1888 Burnham & Root building that included a lobby by FLW. As luck would have it, Harboe was the intern-architect-in-training at the firm, and he amusingly recalls “I was the guy who knew something about preservation.” The rest, as they say, is history. And so, began Harboe’s presentation to the UO audience.

Harboe initially presented his work with the Rookery, completed in 1992. Revealing intriguing details such as how each window had to be removed, all original sashes put back in place, and having to cope with 4000 corners of fenestration where water had ample opportunity to leak in (and it had), Harboe walked us through the trials and tribulations of careful, accurate and painstakingly detailed historic restoration and preservation. Removing approximately 20 layers of black paint from the oriel staircase (removed and cleaned by crushed walnut shells under pressure), and having to rely on a creative interpretation of replicating single piece teardrop elements as two pieces glued together, the architect-preservationist confided aspects of the process to reconstruct the original LaSalle Street and Adams Street lobbies to the original [circa 1910] appearance. Harboe spoke of the importance of finding sources to help recreate or restore elements to an historically appropriate form. This might include the use of historic photographs, finding a small but original fragment of wall or flooring, or simply cleaning a surface down to a semblance of its historic original. Graciously offering credit to the workers and craftspeople who joined him on the project, Harboe firmly advocated for the importance of hiring “the right people for the job,” saying “craftsman make a difference.”

Harboe’s preservation, restoration and rehabilitation of The Rookery was praised by both the architectural and historical preservation professional fields as well as the city of Chicago. Having completed this very successful project, Harboe moved on to his involvement with the Reliance Building, also by Burnham and Company (1891) and completed by Charles Atwood (DH Burnham and Company, 1896). The Reliance Building is one of the most important early skyscrapers in America. At this point, Harboe paused to address the importance of the Federal Tax Credit to his historic preservation work. Harboe explained the effectiveness of the Federal Historic Preservation Tax incentive program as contributing to positive and cost effective public/private revitalization programs and, hence, directly influencing his projects.

The Reliance Building (renamed and converted to the Hotel Burnham in 1999) has been termed “proto-modern” by architectural historians. Its expansive and elegant fenestration and strip-like sections of white glazed terra cotta are distinctive and highly relevant to its design. Like all of Harboe’s projects he addressed during his lecture, the building is listed both as a National Historic Landmark and a City of Chicago Landmark. Harboe noted the remarkable steel curtain wall that is made up of an internal steel two story-high column and provides all structural support for the building. He also spoke of the importance of being creative and flexible when needing to find substitute materials. For instance, the windows in this building were beyond repair, they were replaced. The original cornice that had been removed in 1948 was reconstructed in cast aluminum. Even with these alterations, Harboe stayed persistently true to the original patterns. Harboe further emphasized his use of historic photographs, drawings and remaining fragments in the detective-like job to authentically replicate a structure. Harboe also brought up another important issue in his historic preservation projects, that of the importance of place and infusing a place with renewed vitality. The primary focus of this historic preservation project, he commented was to “give life to [the street] and that [was] the intention of the project, to revitalize.”

Harboe’s work on the Sullivan Center (built 1898-1904) involved all exterior restoration, Federal Tax Credit Program consulting, and City of Chicago façade examinations. A building best known for the elaborate cast iron storefronts and a curved rotunda, the project truly relied on the Tax Credit incentive; Harboe briefly discussed how his focus had to fixedly remain “not doing anything that would jeopardize the Tax Credit.” In order to create the necessary elements for this building, Harboe turned to a sculptor to recreate the details characteristic of the original designer, Louis Sullivan. Working with a craftsperson familiar with the techniques available to create ornamental work was of great importance. With exceptional workers, Harboe maintained his team was able to place remarkable attention to exact detail and towards the investigation of existing parts to restore this building. Speaking of the reconstruction of the ribbon windows, the matching of the colors for the glass elements, and the color matching for the terra cotta (working from found fragments buried deep within the walls), Harboe stressed the challenging aspects of his work. Turning to an amusing anecdote of good fortune on-site, Harboe recounted the team finding a large fragment of paint that had been trapped under a canopy. The fragment would consequently be used to attain a correct color match and be the most formative piece leading to an accurate hue. Using and having a knowledge of forensic investigative-like techniques is very helpful in the restoration field, commented Harboe, noting that he relies on such investigative strategies for each project.

Much of the cast iron work for the Sullivan Center was done off-site. Harboe recalled how this turned the project into a gargantuan job with disassembly of parts that “in many cases were held in place by the friction of the corrosion.” Harboe added that this campaign of difficult structural situations made each stage arduous especially with the added logistical difficulty of having to remove each piece to an off-site location.

Harboe’s work on the Chicago Board of Trade Building (1929, Holabird and Root), one of the finest Art Deco style buildings in Chicago, began in 2004 with renovation efforts to restore the Art Deco aesthetic of the lobbies, improve elevator operations for 24 elevators, and modernize building systems. The building was of particular importance to Chicago as it is viewed as a symbol of the city. Harboe began this project by cleaning the exterior limestone surface of the structure simply with water. He advocated for using “environmentally friendly substances whenever possible.” Important features of this project included the interior lobbies with six varieties of marble, nickel silver metal trim and ornamental plaster as well as a luminous ceiling featuring a panel of light. All of the lobbies were illuminated by stylized fixtures using nickel silver frames and glass, the challenge here was to recreate missing fixtures, and nickel silver features. On this project, Harboe related finding some original treated elements that became key pieces to the restoration. Harboe’s keen attention to detail and his willingness to really look, explore, observe and delve into the hidden pockets of a structure and find minute details of ornamentation, color, and materials has lead to many of his discoveries that end up being the pieces that put the puzzle of historic restoration together. The necessity of being able to look and investigate, research and uncover is one of the most important aspects to any restoration project and cannot be underestimated.

Commenting on his experience with all these projects, Harboe again emphasized the importance of the workers who help realize the projects. “The tradesman make the difference,” he asserted. Concluding his lecture with this advice, Harboe took questions from the audience.