On Monday, November 12, 2012, interior architect, Jody Pene, IIDA, LEED AP, and former principal at GBD Architects, presented her lecture, Forty Years: Looking Back and Looking Forward, to a Portland, Oregon audience at the University of Oregon in Portland, White Stag Block. Pene is a visiting professor at the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts Department of Architecture and the current University of Oregon Margo Grant Walsh Professor in Interior Architecture.

Pene gave her presentation as part of this year’s Gunilla Finrow Distinguished Lectureship in Interior Architecture for the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts. Gunilla Finrow attended the lecture. Commenting on Professor Finrow’s attendance, Pene said,

I was very honored to have Gunilla Finrow, for whom the lecture series is named, come down from Seattle to attend my lecture. And pleased also to have many colleagues, students and friends both from the university and from the Portland community attending. Some of which were from GBD Architects and team members on many of the projects I presented. It was nice to be able to share the highlights of my career with both old and new acquaintances.

Associate professor Alison Snyder from the UO AAA Department of Architecture introduced Pene, commending the visiting professor on a long and varied career that involved significant commercial and graphic design work and color expertise. Snyder remarked favorably on the opportunity to have Pene deliver her lecture both in Eugene (November 7, 2012) and in Portland; noting that it is a privilege to be able to “bring what we do in Eugene outside of Eugene to Portland and beyond—being seen and heard in places farther away” and to have the ability to provide lectures of this content and calibre to an interested community and metropolitan audience, such as that in Portland.Pene, in addition to her visiting professorship, is also on the UO AAA Board of Visitors. Professor Snyder thanked Pene for her ongoing and multi-tiered involvement with the UO School of Architecture and Allied Arts.

Beginning by illuminating her design philosophy, Pene spoke of several key factors that have played a major role in her career: the need for having a strong concept, recognizing an individual culture and goals, and being able to identify the appropriate environment of the business or client—these factors merge together in the creation of a project solution that is unique to each design venture.

Pene graduated from the University of Oregon in 1972 with a bachelor of interior architecture. She immediately moved into her professional career relocating to Pittsburgh to work in graphic arts and interior design. At this early juncture, she found value in working with a team-based approach and discerned significant demand for her skills in signage and graphic design. In the 1970s, Pene relied on her, what she calls “old fashioned” handcrafting skills of drawing everything by hand and using tools such as pastels and pencil to convey ideas.

It was early in her UO studies and work career that Pene discovered her great love of “color and the play of patterns.” Calling upon this interest and her ability to bring together meaningful and attractive explorations of color and pattern once in a professional context, Pene’s career blossomed. She returned to the West Coast in the late 1970s to begin work with two highly significant Oregon architectural firms, Boora Architects (1978-1984) and GBD Architects Incorporated (1984-2010) where she held the position of principal for sixteen years and the principal-in-charge of interior design for twelve of those years.

Pene spoke of realizing the importance of collaboration in projects and of working with the entire team to create a strong concept. While her expertise would lie in the designing of the color palette and graphic arts component of the project, she consistently realized that it was vital everyone in the firm work together to pull the project together to create something remarkable.

Pene feels a pinnacle of her career came with her work on the renovation of Portland, Oregon’s Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall. Here she worked on the interior to come up with fifty-four new colors that would accentuate the Italian Renaissance details and inform the aesthetic of the greater interior. Everything from overall carpet patterns and specific border patterns, to the overall interior design concept complete with soaring theatrical spaces culminates to present a space of intricate detail and graciously considerate historical appreciation. It became a space uniquely suited to its culturally-grounded purpose.

During her lecture, Pene discussed her range of work incorporating independent interior projects such as those at elegant Portland accounting firms and law offices. Pene recalls that she remained true to her own design philosophy whether designing way-finding signage for a stadium or the exclusive interior of a highly prestigious law firm: the importance of designing to the individual personality of the firm or the business always remained at the forefront.

As time passed and her career continued, Pene began to realize changes in the field and practical changes in the greater societal situation that would have consequences for how she worked and what she designed. In the early 2000s, Pene saw a shift in how people would relate to a building and how the interior design could be used to create spaces conducive to stimulating creativity. The design work at Wieden + Kennedy’s Dekum Building illustrated to her how a more casual building “painted white and with playful sculptural forms” could be used to encourage innovation and creative work.

This was a change Pene had seen emerging about a decade earlier. As the 1990s had progressed, she noticed that there was a transition occurring from traditional design to design that was more responsive to change and to the creation of warmth in spaces –spaces that could foster person-to-person interaction, collaboration, and conversation.

The future of design, says Pene, was venturing into the realm of exploring flexibility and adaptability in the workplace. This new approach embraced the concept of an open office that can be re-configured to contribute more effectively and cooperatively to a collaborative workforce. Some of the initial big businesses to adopt this free and flexible design philosophy were places like Wieden + Kennedy, Columbia Sportswear, and Nike. Pene’s design theory, readily adopted by the aforementioned clients, forged ahead creating spaces that affirmed creativity while retaining corporate identity.

By establishing connections to the corporate ethos and maintaining strong ties to the sense of a unified whole or corporate campus, Pene was able to design spaces that respond to a human element, are comfortably sociable, and encouraging to innovative thought. In addition to being sensitive to place and her understanding of the humanistic component, throughout her career, Pene advocated for a palette of materials as well as colors that would allow a positive psychological emotional response, physically provide a comfortable space, and energize inventive behavior. Sometimes inspired by “aesthetically unconventional interiors,” Pene spoke of the ability of a space to encourage or foster creativity and innovation.

As changes occurred in the economy and global marketplace, Pene traced progressions in the way designs changed for her clients. Developments in environmental considerations brought new products and the desire for sustainable materials. Pene saw opportunities to integrate the newly renovated spaces of previously industrial buildings into simple and contemporary spaces blending the existing exposed structural elements as a beautiful, raw part of the entire concept. Patina-coated steel columns would become exposed, a testimony of history and permanence and be combined with a new concrete structure to produce a relaxed and informal atmosphere encouraging teamwork. [Such as with GBD’s new Pearl District building.]

These innovative design principles intentionally promoted client and staff intermingling which was a distinct shift from the decades previous where offices might be cubicle-style, isolated or closed off to integration and interaction with others. Pene explained the changes in the nation’s economy and the world led to a more competitive global economy. This, in turn, brought about another change in the needs of corporate and office design: with the new digital age was the demise of the on-site printed book or need for prodigious library-like rooms in design projects for law firms. Instead, research could now be done online, at desks with computers in shared spaces and more open places.

Another change, altered the ubiquitous conference room. Communication was more electronic and conference centers could have multi-purposes with the invention of privacy screens and glass (technological innovations that changed the needs of the space). With economic and financial considerations in mind, saving money and cutting costs was a definite concern, too. Consequently, only one floor needed to receive and be open to the public thus decreasing overhead costs. Spaces were becoming lighter and brighter. People were to be encouraged to work together, to create in a more warm and welcoming environment and to realize to potential of shared spaces and daily interaction.

Pene highlighted development of trends we might consider commonplace today: the on-site workplace cafe and simple, social gathering spaces. Both of these concepts encourage on-site lingering collaboration, conversations and teamwork. People stay together longer, have more conversations and work gets done leading to greater productivity and the exchange of ideas. Even the advent of more modular furniture in the workplace allows for more space and more efficiency letting departments grow and shrink, use space and easy-to-move furniture as needed, and be more flexible to the needs of people.

The interior designer described how previously high-end law offices began to transition to interior spaces that were “home-like in quality” rather than strictly formal, dark and heavy. Pene associates these specific developments with creating spaces that let people “linger, relate, converse, and exchange ideas.”

Summing up her recent projects with slides of the Meriwether towers on Portland’s South Waterfront and the Center for Health and Healing (OHSU), Pene discussed her continued exploration into a design philosophy that creates a “living room feel.” At the Health and Healing center, Pene designed an interior that was restorative and innovative while being LEED Platinum: she was stunningly successful. She spoke of her work with Camera World and how she limited the palette there to mirror the products relying on black, silver, and nods to technology as a overall theme.

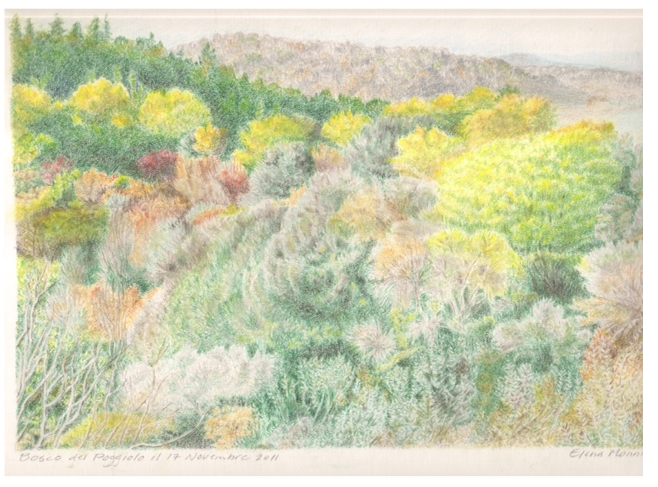

With a full and productive career, Pene now plans to continue semi-retirement sharing her time between Oregon and her beloved home in Montone, Italy where she finds pleasure in photographing and drawing the fields and farmland. This rural Italian paradise provides Pene with plenty of time to discover history, art, architecture and landscape…..and she continues to enjoy depicting her environment (by hand) in pastel, appreciating and being “enthralled by the seasons, the colors, the patterns.”

Pene showed a series of her photographs and pastels: a collection of images including poppy fields, mustard fields, a field of onions in bloom, sunflowers, an olive orchard. She spoke with great affection for the natural and agricultural environment that surrounds her in Italy and explained the “sense of revealing, in color and texture and shape, the potential of light and shadow, the symmetry and order, the curve and line, even in a random, eclectic pattern of blooming poppies in a field.”

As she looks towards a future well-immersed in the things she loves and still active in a field she has made great contributions to, Pene noted that with her recent experience at the University of Oregon as an instructor, she has now discovered a new interest: teaching and working with students. She would like to teach abroad in Italy to exchange students traveling there for the first time. Her career, she says, has allowed her to see the importance of international study to enhance the forward progression of one’s design ability and knowledge, reviatlizing creativity and bringing fresh perspectives. She encourages all students to step into the international sphere of educational experience to ignite their creativity and expand their reference. And, even in an age of digital dominance, students, she recommends, still need to learn to draw by hand.

Regarding her own continual exploration of trends, and innovative design thinking, Pene says she relies on her photography, her sketching and various sources of media to help inform and expand her knowledge and bring inspiration. She also gratefully acknowledges her frequent world traveling and attendance at fairs such as the The Milan Furniture Fair (Salone Internazionale del Mobile di Milano) and NeoCan Chicago as key in continuing to fuel her creative energy and staying appraised, or even ahead, of trends. Keeping in touch with the pulse of the contemporary design field is further accomplished, she says, by reading a plethora of online sources and publications.

A current that continually flows through Pene’s design work and consistently infuses her ability to design meaningful, thoughtful and yet dramatic and captivating interiors, is her understanding of the importance of collaboration on her projects. While she acknowledges the design community has changed over her forty year career, she cites how important her graphic design experience has been in assisting her creative work from the beginning. There is “a strength and a clarity” to projects today, she remarked, to the way people work together which she finds quite beneficial and refreshing. Being conscious of patterns and color, and tying a project together by identifying what is required to accomplish the specific goals remains the main objective of Pene’s work ethic. She emphasized the interaction between all involved, but overall, it is the sense of collaboration that is the sine qua non of every project.

Remarking on the tremendous changes in the design field, both in approach and materials that has taken place during the last four decades, Pene recalled that as trends emerge, and change is inevitable, the observation of what is needed, and wanted and being able to adapt that to a design is a vitally important aspect of any project.

The years have defined a gradual progression in her work projects—projects that moved from the creation of formal spaces to the innovative and imaginative formulation of casual spaces. And along with this inventive approach to the workplace, human, and space interaction, Pene has seen that letting people be comfortable encourages interaction, bringing about more creative and worthwhile production, and, in the end, making a more successful product.

Read the UO AAA News Story here, for Eugene. And for Portland.