Lecture: Confessions of a Failed English Major: Buildings and Texts, 1900-2010

The following is a summary of the recent lecture by Professor Edward Ford presented at the

University of Oregon, Department of Architecture

School of Architecture and Allied Arts in Portland

November 12, 2010

In 1993, the Pietro Belluschi Distinguished Visiting Professorship in Architectural Design was created as a perpetual endowment fund to foster and promote education in architectural design. Pietro Belluschi (born in Ancona, Italy, 1899, died Portland, Oregon, 1994) was one of the most respected architects to have lived and worked in Oregon. His influence was felt worldwide. Combining innovative technical vision with a sensitivity for composition, the merging of crisp lines and geometry of the International style, and harmonious poetic building expression, Belluschi called for “function, technology and social service” in his buildings. Belluschi was one of several architects recognized for crafting the Northwest Regional style of architecture.

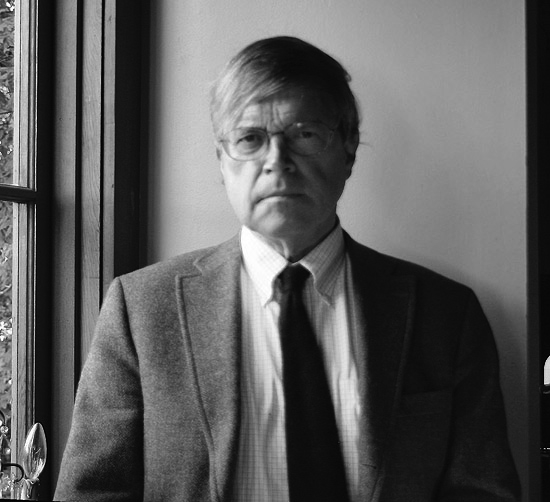

Most currently, Edward Ford, Vincent and Eleanor Shea Professor of Architecture at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, was awarded the prestigious professorship. Ford visited the University of Oregon this November (2010) to present his lecture, “Confessions of a Failed English Major: Buildings and Texts 1990-2010.”

Reviews of Ford’s recent books have praised him as an architect and academic turned novelist. Ford’s lecture gave an illuminating account of his personal background, and his synthesis of architectural design and theory, practical and personal experience and literary connections.

Edward Ford began his lecture with a confession: not that he had failed as an English major but that as college student, he had failed to major in English and, despite his youthful aspiration of becoming the next great American novelist, he never did write an undergraduate work of fiction. Instead, he embarked on a scholarly course that would lead to a distinguished career as an academic and an architect, and mid-career, a writer. Highly praised for The Details of Modern Architecture (volumes I and II), these works did not show Ford’s literary inclinations and engaging flair for well-written almost novel-like books. With the 2009 publication of Five Houses, Ten Details, Ford allowed a glimpse into his ability to provide engaging and academically informative work. And, progressing even further, in the spring of 2011, Ford’s The Architectural Detail will be published, another architect-as-novelist piece.

Above all, Ford is an architect fascinated by detail, the expression of detail and the architect’s ability to either conceal or reveal a building’s structure and materials via this detail. This interest in detail is also expressed in his respect for the Russian Constructivists (artists, sculptors, and authors who rejected art for art’s sake and instead advocated for art to embrace a social purpose and practice). Not only is Ford influenced by the Constructivist philosophy, their abstractions devoted to modernity influencing his own work, but he also has found an influence from writers such as Faulkner and “The Sound and the Fury”. Indeed, one can look at the work of Ford with its sleek geometry, its experimental lines, its details revealed, and its emotional distance, and see an architectural stream of consciousness, similar to that in Faulkner’s writing. This is one way to find truth, Ford asserts. Objective forms that transport universal meaning where elements are broken down to the most rudimentary and basic level. Ford cited comparisons between modern and ancient building and the use of technology in both as he declared: “You cannot separate form from material.” Nor “the easy from the complicated” as there exists this inescapable juxtaposition between the two.

Recalling the architects of ancient Greece, biblical references with a mention of materials used, and even Frank Lloyd Wright, Ford remarked that concentration must always be kept on “form” — as it is the form that is the most important, not the material, however, realistically these cannot be separated. “Form is inherent in the nature of the material,” Ford says, “Could you design in another way?”

From comprehending buildings as a complete entity, Ford sees associations between the structure and the building as essential: he considers weight, empathy, joints, and animation. It is the association between these concepts that lend the societal aspect: “an understanding of the physical forces because we understand ourselves.” However, he continued, it is “structure that is a primary concern.” Commenting that buildings are assemblages put together as parts, and that it is the fundamental and absolutely key role of the architect to determine how many joints or parts a building has, Ford says this contributes to the visual aesthetic of the building, therefore, it is the understanding of the parts that makes the the whole: “Architecture is about deciding how many pieces a building has.” People, claim Ford, have the capacity to understand buildings as parts that are stable as in an equilibrium of forces and, consequently, more than just a building.

Emphasizing the theme of understanding parts to the whole, Ford said that to grasp the inner forces of a building and to see those parts represent something larger than the parts is the fundamental component of architectural design. he explained that there are both animated joints and static joints, or parts. He compared the designs of Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, and Le Corbusier and that of the simple log cabin. Ford considered both the rustic and the classic in an examination of what truth in architecture is. He noted even the rustic log cabin is a structure dependent on modern technology as the cutting of the logs is, and has been throughout history, linked to machines and technology. With insight into the built environment of both Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, Ford noted that as Thoreau had used recycled mostly shanty wood (not logs) to build his cabin, and Muir had been a sawmill owner and operator, both had relied on modern technology. The log cabin, itself, asserted Ford, is, indeed, “an industrial product and a modern building system.”

Addressing the idea of the simple and the small, shed-like building being a modern and technologically dependent product, Ford has architecturally experimented with the blurred line and overlap between dual functionality. Combining furniture and architecture, and attributing all visionary brilliance for this to FLW, Ford detailed a period of discovery by changing his attitude towards furniture as an architectural component and saying, that inspired by Wright, he turned to furniture as “little buildings” both sculpturally and architecturally. This eventually led to an in-depth examination of libraries, both modern and historic, and book stacks with the possibility of the integration of books and furniture bays within the library as a structure. Ford explained his vision of a unit where all the same materials would be used to make one component piece of functioning as, for instance, a democratic table—one table for all (from the student to the director), and the pieces of this furniture continue up into the structure to be pieces of the architecture. It is a functional approach that encompasses minimal themes and a basic element broken down to create a whole unified piece.

Ford briefly transitioned to modern buildings that are not about expressing technology but seek to hide it with the means of using technology. Ford commented on the predominance of modern glass buildings that have windows without visible frames as evidence of this rejection of conspicuous technology. Ford stressed that what is important is how much a building is able to explain what it is about: exposed ducting, conduit, animated joints, a frame that moves in and out of a building—these are objective forms transporting universal meaning.

As the tour de force of his personal architectural design expression, Edward Ford designed, and supervised the building of the Ford House, “a very American house” and his own family home. Ford remarked that building this residence gave him the experience and opportunity to experiment with his own architectural theories on truth and abstraction. The building became a place where he could express an admiration for machines and technology and a devotion to modernity, geometric form, and experimental theory and structure.

Reception Highlights

Prior to the Lecture, Edward Ford Joined

Students, Faculty, Staff and Members of the Community

for Introductions & Conversation

Story and Photos (unless otherwise noted): sabina samiee