The official motto of the UO School of Architecture and Allied Arts is “Make Good.” Students in Sara Huston’s Furniture Design course this last fall 2011, took that one step further. Huston led her students on an interdisciplinary exploration of furniture design with the intent to “make good”—better. The course offered in the Product Design’s Portland program, Conceptual Furniture Design | Private Space (PD410) launched an experimental foray into furniture as a catalyst for creating meaningful experiences and interactions between the object and the user. Not only were students welcomed from all Portland programs to enroll in this course, but regionally-based community members and professionals in the design fields were invited to participate, as well. All the students found themselves challenged to embrace their backgrounds whether in architecture, art, or design to create pieces that illuminated ideas and provoked thoughts far deeper than your run-of-the-mill kitchen stool might elicit.

In what became a fantastic combination of the relationship between human behavior and product design, the course moved along with each student being required to develop a piece of furniture that might be found in the home environment. Once the design was completed, students worked on creating production documents to be used in communicating design intentions to fabricators. As a final step,students took part of their creation to the White Stag model shop, the Fab Lab, and built | prototyped the piece with the technical expertise of John Leahy and guided by Huston.

Student Ariana Budner commented on her experience in the course:

Although all of our designs were initially based on a lifestyle (ie. spiritual life), what was interesting to me was how each person began to focus on different components of the design — material, process, overarching concept — to dictate their final piece. For example, I wanted to learn how to use the CNC router, therefore, the concept of the turntable, grew out of the tool’s capabilities.

What I liked about the design approach in this class, specifically, was the diversity and breadth of skills I utilized, learned and strengthened within the ten weeks of the class. We were encouraged to work with fabricators, yet build what we could by hand. I learned a great deal in regards to both. And I enjoy the fact that my turntable is a fusion of my hand-crafted woodworking, digital woodworking, a fabricator’s welding, and a mass produced electronic.

The progression from idea to a tangible piece of furniture was revealed at the course’s final review in early December 2011. The process had guided students down a path of understanding history and precedents of domestic furniture culminating in how they could create furniture with more meaning while encouraging them to defy convention. Focus was put on researching a user’s physical and emotional relationship with furniture and how to blend form, function, and design conceptualization.

When the pieces were put on display for review, the assortment was impressive: students showed a knowledge of materials, and finishes, and had crafted by hand or worked alongside manufacturers to help realize their designs. They engaged with reviewers and spoke about their work, explaining connections to the people who would be using the pieces. The exhibited pieces had been made of natural or deadfall wood, and materials that were completely formaldehyde-free or recycled. Concepts of reduce-reuse-and-recycle were plainly evident. Local manufacturing was the preferred option. This was the brave new world of furniture design. And as reviewers such as Reiko Igarashi , Kate MacKinnon, John Paananen, Dave Laubenthal, David Bertman, Leslie Biggs, and Brian Gualtieri joined the dialogue to critique the designs, the students’ creations received both constructive criticism and praise fueling the realization that furniture design for the home can be a highly provocative topic.

I recently had the opportunity to talk with Sara Huston about her interdisciplinary product design course. I wanted to discover how she was relating intention, process and her ideals of humanitarian-based design. Huston explained that her Furniture Design course was all about collaborative design, interdisciplinary blending of talents and the understanding that to create something meaningful sometimes you need to “step out of yourself.” This sounded fascinating, so I asked her to continue and to illuminate what it is that compels her visionary approach to furniture design and creative exploration of the form into an object of daily use. The Cranbrook Academy of Art grad (MFA 2007, 3D Design) will quickly assure you that it is her sense of curiosity about “human behavior, human emotion, and how we connect with objects.” She further explains that this element is “something shared with the design profession….To be even more inclusive.” Huston continues, “it is all linked to physiology, sociology, and anthropology.” Talk about interdisciplinary….Huston feels that if one gathers the skills to enable “knowing the right formal expression, proportions, colors and compositions” one can use this melding of experiences to craft a compelling piece. Sometimes the most compelling pieces disrupt expectations and bring attention to passive human behaviors. “Just imagine,” says Huston, “how a table placed between two people affects their conversation, their body language, the way they interact with one another.” Remove that object, and the situation changes or shifts—no longer is there a solid object that projects intention and spatial relationships to a face-to-face encounter.

Huston is fascinated by the intimate, or lasting, relationships people establish with “stuff”—objects that are kept for a lifetime versus objects that are casually disgarded. What decides how objects are treated, what gives meaning to a piece? What makes one piece end up in a landfill and another remain a decades-long fixture in one’s living space? Huston believes that if an object does not hold something personal or evocative to a human’s emotional situation, that piece won’t be kept for long—it becomes meaningless, valueless. Posing these inquiries to her practice and embracing the somewhat controversial philosophy of product design as an art and not just a design, Huston enthusiastically promotes her process as akin to a brush thick with paint stroking a canvas-like sense of “freedom to absorb the world around [her] and reinterpret [her] surroundings.” A painterly metaphor gracefully upholds her firm stance that objects must contain an emotional and empathetic aspect. Thereby, her intention is to make design secondary to art, but to retain both as inextricably interwoven. Every created piece must have a rich story: have meaning, value and intention that moves forward with emotion and purpose. Lofty ideals to accomplish, indeed. But Huston is certainly the artist | designer to do just this. Her educational background (in addition to her MFA from Cranbrook, she holds a BFA in Sculpture from the Art Academy of Cincinnati, 2004) and her penchant to self-teach practical methods of woodworking and the technology of tools, has turned this ‘humanitarian artist of the object’ into a realm that rises with silky smoothness over and above only product design.

These ideals are interpreted to provoke a design discourse discussion. Huston seeks to get her students to feel empathy with the users of their artistic furniture or, conversely, their furnituresque art, to perceive values in objects that can create a more fulfilled or meaningful life. Perhaps this is a new thinking, feeling, almost psycho-analytical development to product design, dare we say, a kinder, gentler way—the desire to encourage students to create objects that make people think and feel and respond to their environment? Huston would, in her charmingly bashful manner, say that her goal is simply to challenge these young people, to show them furniture is “the muse”. It is not new, it is not revolutionary, she says, but it is a way of teaching product design that puts people first, and commercialism and materialistic acquisition firmly in second place. Students are taught that pieces with little intention and devoid of meaning are quickly put aside.

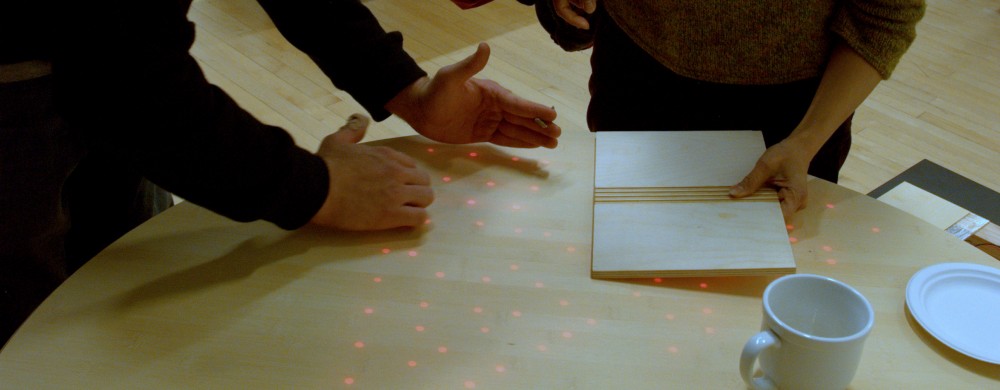

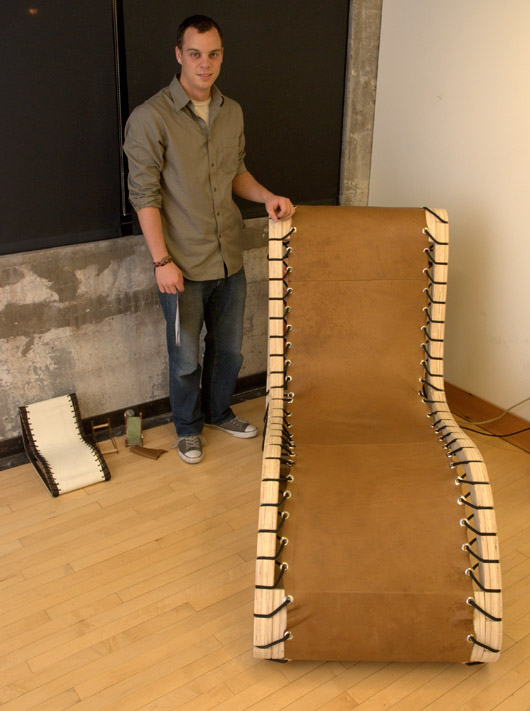

All of this translates to a course where Huston recognized the creative potential of reaching out to architecture and art students who might not yet have been exposed to furniture design, might not have thought about humanitarian furniture objects, might not have considered the emotional power of a simple usable furniture piece but who already are learning to practice the same inquiries in their creative design. Huston saw this as a chance glance through the lens of their architectural or art learning and realized an advantageous opportunity apply it to day-to-day, hands-on, immediately buildable pieces. With furniture design, Huston could enable her students to explore that their ideas as designs that embody design as a tool to positively effect their environment and draw attention to elements of living on a touchable, comfort-providing level. We see the soft stacking layers of Danielle Thireault’s Homasote chair; and the gentle undulating concave a la convex of Seth Dunn’s chaise longue. And something as basic as a dining room table could be transformed to become integrated with digital, motion-sensitive lights and visually display human movement and interaction, or lack thereof, during a sit-down dinner. Student, Adam Wilson’s table was a captivating commentary on the health of the modern family, a solid recognition on the collapse of a strong family unit –if the family sits down together the red lights dance in response to human motion across the surface of thetable. The piece remains dark with no human interaction.

Discovering how furniture can relate to and express the human environment, as ideas from solitary sitting, to interactive motion-sensitive devices to pieces that would efficiently spin vinyl and simultaneously hold records illustrated how these students were critically thinking about the functioning world around them, how people relate to spaces and items in those spaces and everyday objects that might provide some glimpse into how we relate to one another. Not to mention, what objects they felt people held or could develop an emotional attachment to. The empathy is found in designing for others and their specific lifestyle: pieces had to work with a humanistic element and had to have an emotional anchor, they had to challenge expectations and react. Students had to grasp what creates furniture. And what compels someone to like something inanimate: what prompts an emotional response, a table, a chair, an object that can hold something of value.

It had been Huston’s keen interest in discovering and developing the possibility of interdisciplinary creativity that would help students see a breadth to their ideas. This concept ultimately led Huston to propose her furniture course series. Huston remembers herself grappling with design versus art concepts during her undergraduate days: the art aspect flowed easily, the design component seemed to be inherent. Did the two need to be separate or as her practice suggested, her work seemed to embrace the dichotomy. She recalls an immediate connection with reflective artistic practice, it resonated with her from the onset of her creative endeavor, and “just” designing seamlessly gained her artistic flair. Huston comments that now having her own established studio and professional practice,The Last Attempt At Greatness, has allowed her to realize a niche for crafting objects that are woven with aspects of humanitarian thought, sustainable sentiment and a challenging process. These were all aspects that would ask students to think differently about standard, everyday objects of furniture. Blending this into a design ethos and getting her students to visualize making furniture as a lasting and influential process made the interdisciplinary combination essential. Huston blazed ahead, her students expressing gratitude for the progression.

Student Danielle Thireault, commented:

The furniture course was the first chance I had to really integrate my architectural and product design educations. It allowed me to consider the spatial implications of the piece, as well as the user interactions. I really enjoyed the experience and appreciated being able to fabricate a concept and get a better grasp on the breadth of processes included in the production as an individual piece, as well as what considerations to take into account on a mass production scale. The environment of working amongst both architecture and product design students also encouraged avariety of exploration that, for me at least, was key to the development of my chair.

The initiation of the furniture series to inaugurate the interdisciplinary coursework at the UO AAA in Portland reflects a passionate, and increasing interest among students and professionals to participate in projects that extend to a greater community in ways that show positive, meaningful, connected work. Huston’s philosophy that asks students to think critically about and be cognizant of the history and social context fosters a much greater contribution to the product design field than simply approaching furniture design from a commercially viable viewpoint. Huston shepherded her students to experience and to merge with the environment they would be creating a useful object to be placed within. And as Huston likes to point out, this method can produce commercially marketable pieces appropriate for a mass-marketplace. However, she is quick to say that for her frame of reference, making things involves more than producing a sell-able item—and this, perhaps is what results in Huston’s craft intention being art first, design second. Or, maybe, intentionally, art that inspires comfort and connection because it just might be your favorite chair and something you feel an emotional connection to.

Our students, future architects, designers, artists will help fill our world with ideas. If they are offered opportunities to collaborate with those ideas, to work within all creative disciplines and to craft work that truly serves a population the field will blossom. Huston feels that it is with students that we “see the most innovation of all.” They are not afraid of failure, they take risks, they question what exists, they try things. This is why Huston says her best and most interactive audience is her students—“they feel the freedom to think and create what might never have been done before.”

Taking this energy into her spring offering of PUBLIC FURNITURE, Huston will be working with students who are interested in the competition, Land Art Generator Initiative, [LAGI serves to educate and inspire people about the potential for renewable energy generation infrastructure to become integrated into the aesthetic of our cities in ways that contribute to the cultural richness of the built environment.] Interested students can register starting March 2012 for this innovative class experience.

Providing key courses that encourage students understanding about the built environment, from the skyscraper to the stool, continues to develop an understanding of collaboration and bringing together ideas, a confluence of creativity. The intersection of thoughts, as Sara Huston advocates, can make good, very good design, but also it can make designs more thoughtful, more sustainable and more connected to the populations that live and work and play with them. From chairs to record player shelves, from tables to work stations, Huston’s class brought together a myriad of students who with different perspectives who had a vision to build something interesting and really think before, during and after. Design merged with art . . . . and it was stunning.

Photos of the student work from the fall 2011 Conceptual Furniture Design | Private Space (Product Design 410) course and the December 2011 review follows.

You can learn more about Sara Huston on her website, The Last Attempt At Greatness. She is currently exhibiting at the MADE LOCAL: Products of the Pacific Northwest show, February 14-29, 2012 at the Bellevue College Gallery Space in Bellevue, Washington.

story and photos sabina samiee

One comment on “Sara Huston's Conceptual Furniture Design | Objects of Empathy”