Like video, Cinema Studies has basic standards for audio recording.

In general, when you are working with a camera or an audio recorder please record using the following standards:

1. Audio Format: WAV file

2. Sample Rate: 48kHz

3. Bit Depth: 16

4. When using one microphone, record in MONO

5. When recording, try to set your levels for a range between -12dB to -6dB. When you are mixing audio in post-production and exporting, take care to make sure that those levels do not exceed -6dB, which is the standard.

A BIT ABOUT AUDIO

Recording sound is the process of converting sound (air pressure movement or acoustic energy) into digital audio/information. Once captured the digital audio is represented as a waveform. What you are recording is information about the amplitude (loudness, which is measured in dB/decibels) and the frequency (bass and treble) over time, which is also represented in the waveform. This information that you record represents the sound as digital audio.

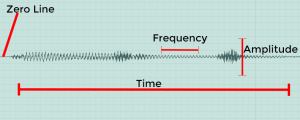

When you look at a waveform in post production it will look something like this.

Zero Line: This is where there is no sound or movement in air pressure.

Time: Time is literally time of recording, or the time axis (horizontal).

Amplitude: The larger the waveform gets vertically the louder the sound is. This is measured vertically on the amplitude axis.

Frequency: This is representing bass and treble and happens horizontally along the waveform. If you see waves that are tight or close, that is a high pitch (treble) sounds, while waves that are spread out are low pitch (bass) sounds.

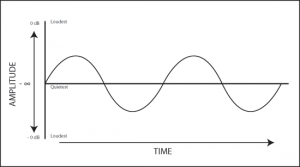

Here is a zoomed-in look at a waveform.

WAV vs. MP3

As general practice, never record audio in the MP3 format. It is a highly compressed audio format that was made to easily distribute audio (and at one point video) online. It’s fine for listening, but you want to record audio as a WAV file. You will find that WAV files are much larger files than MP3 files; in fact, about 10 times larger.

Because recording sound as audio is making acoustic energy into data, an MP3 file simply lacks data during the compression process. Thus, you lose information regarding frequency (bass, mids, treble), amplitude, etc. In order to make for much smaller files, MP3s remove quieter sounds and frequencies that may be inaudible to the human ear. WAVs capture all of this information.

To think about this using an analogy: a WAV file is like recording moving images onto 35mm filmstock or taking a picture as a RAW file, whereas an MP3 is like a Quicktime .MOV file or a JPEG.

SAMPLE RATE

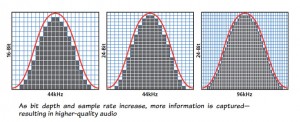

Both sampling rate and bit depth affect the resolution or quality of a file.

Capturing information about frequency and amplitude over time is a process called “sampling.” The sample rate is the amount of samples per second, or sample points per second; essentially it’s the number of times per second information about a sound signal is being captured. The higher your sampling rate the more accurate the digital representation of the sound’s frequency (bass, mids, and treble) will be. Sampling rate also refers to amount of information capture horizontally along the time axis of the waveform; it is about frequency resolution.

The DVD and broadcast standard is 48kHz, while 44.1kHz is the standard for CD audio. You can of course have higher sampling rates (i.e. 96kHz), but you should record in 48kHz until you understand this concept more.

The rule about sampling rate for recording and audio projects in general is known as the Nyquist theorem. This states that the sampling rate must be at least twice as large as the highest frequency you wish to capture. The hearing range for humans is 20Hz-20kHz, which means we can’t hear sounds higher than 20kHz (in fact, the true number is about 18kHz). So, you want that sampling rate to be at least twice 20kHz. However, the standard for film/TV is 48kHz .

Please click on this image below as it shows you how audio resolution is affected horizontally as sample rate and vertically as bit depth.

BIT DEPTH

BIT DEPTH

Once your audio signal gets sampled it then gets quantized, which is essentially a process of rounding off between samples. The higher the bit depth then the less rounding off, which means a more accurate digital recording of the sound (see previous image).

Whereas sampling rate occurs along the time axis, bit depth goes vertically along the amplitude axis and refers to the resolution of the amplitude. The higher the bit depth the greater dynamic range (the difference between the quietest and loudest sound in a recording) that you can capture in a recording.

While you may be able to record at a bit depth of 24 or 32, most playback machines cannot even handle that resolution. At some point you may want to explore higher bit depth and sampling rate, which would allow you more possibilities for processing in post production. HOWEVER, for all applications in Cinema Studies 16 bit/48kHz resolution is more than adequate.

MONO vs. STEREO

This is often a misunderstood concept. For most applications, however, mono recording is fine.

We can think of mono recording as using one microphone to capture sound from a source, and recording it onto one track on a recorder. When you play back this recording it will sound the same on the left and right speaker (note that with most recorders, you will hear a mono track in either the left or the right of the headphone monitors).

Stereo is when you use two microphones to capture sound from a source and recording the signals from each mic onto a separate track. When you play back this recording it will sound different on the left speaker and the right speaker because the same signal is captured by two different microphones and each mic signal is recorded onto its own track with its own unique sonic characteristics.

Most of the time in Cinema Studies you will be capturing audio from a singular source, such as an interview for a documentary or as dialog for a narrative piece, using a microphone. Thus, MONO recording is preferred. Some recorders, such as the Zoom H4N allow for Dual Mono recording, which means it will record the signal from one mic to two tracks on the recorder; essentially you will have the same audio on both tracks and all this does is take up space on your SD card.

What is a track on a recorder? It’s simply a space to record to. If you have a one-track recorder it means you have one track to record data to; if you have a two-track (for instance the Zoom H4N or the C100), you have two discrete spaces to different audio signals to. There are other recorders in the world that have more tracks.

What is a channel on a recorder? This is a pathway to a track or an input on the recorder. Both the Zoom and the C100 are two channel recorders. Some devices, like the Azden field mixer, have four channels.

There are special applications in which you may explore 2 mic stereophonic recording in some of our courses.

SOME OTHER USEFUL CONCEPTS:

- Mic level input vs. Line level input: Many audio recorders and cameras have an option for input level. Microphones need amplification for its signal to be recorded, but most line level devices (for instance a sound board or computer) push out a line level that needs no amplification. So, if you set the input level to Line but you’re using a Mic, you won’t hear anything. Conversely, if you are recording from a line level device but have the recorder set to Mic, which is amplifying the signal, you will have a loud and distorted signal. This video explains it. It’s important to note that the Zoom H4N ONLY has Mic level inputs so you will have an issue recording devices that output at line level.

- Phantom power: Many microphones require power to transduce acoustic energy. While some may take a battery to do this (DO NOT USE BATTERIES in the Rode NTG2), most use Phantom Power aka +48v, which is a way of using power from the audio recorder or camera to power the mic. If you have a mic (i.e. Sennheiser 416 or Rode NTG2) they will need this power. If a microphone is a “condenser” mic (it will say this on it), it means it needs phantom power to transduce its signal.

SOME VIDEOS

Here are some techy videos describing bit depth and sampling.

This page was written by Andre´ Sirois for the University of Oregon Cinema Studies Program and is published under Creative Commons license (CC BY NC SA 3.0)