1. Robert Bechtle, ’61 Pontiac, 1969 (oil on canvas, 60 x 84 inches)

Robert Bechtle was born in San Francisco in 1932 and has spent nearly all of his life in California. He studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, majoring in graphic design, and later returned for his MFA in painting which he earned in 1958. Here, he is pictured with his family in the work ’61 Pontiac. As in all of Bechtle’s paintings, the composition is derived from one of the artist’s personal photographs.

2. Richard Hamilton, Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Home So Different, So Appealing? 1956 (mixed media, 10 1/2 x 9 3/4 inches)

Photorealism is typically understood as a branch of Pop art. Bechtle first encountered the work of artists using American pop culture as their primary subject matter during his travels overseas in Europe in the early 1960s; these were the works of the “proto-Pop” artists known as the Independent Group at the London Institute of Contemporary Art, represented here by the work of Richard Hamilton.

3. The New Realists exhibition at Sidney Janis Gallery, NY, 1962

When Bechtle returned from his travels, he saw the first major American Pop art exhibit at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York. This exhibit of “New Realists,” as they were sometimes referred to, included Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, and Claes Oldenburg—artists who would later be recognized as central figures of the Pop art movement. Thus Bechtle was well-aware of the trends circulating in contemporary art at the time he began his painting career. As subsequent images will illustrate, Bechtle engages with similar issues to those of the Pop artists, but diverges in his approach to these issues, as well as his engagement with the photographic medium.

4. “75 Reasons to Live: Robert Bechtle on Richard Diebenkorn’s Coffee,” SF MoMA

In this video, Bechtle discusses another major influence in his work: the paintings of Bay Area Figurative artist Richard Diebenkorn. This discussion contextualizes Bechtle’s work in terms of local influence, which is particularly relevant to understanding his regional focus on Bay Area imagery. The impact of Diebenkorn’s work is further discussed in the Essays section of this blog, as the following key images will continue to focus on the greater and more general influence of Pop art.

5. Robert Bechtle, ’56 Chrysler, 1964 (oil on canvas, 36 x 40 inches)

5. Robert Bechtle, ’56 Chrysler, 1964 (oil on canvas, 36 x 40 inches)

According to Louis K. Meisel––the gallerist who championed the American Photorealists and coined the term “Photorealism”––Bechtle’s ’56 Chrysler is the first true Photorealist painting. Painting cars posed a formal challenge for the artist and he began using photographs to assist him with this process in the mid-1960s. While he was certainly not the first artist to use the photograph as a source of visual reference, Meisel contends that Bechtle was the first artist to work purely from the photograph to create his composition.

6. Robert Bechtle, Agua Caliente Nova, 1975 (oil on canvas, 40 x 69 inches)

6. Robert Bechtle, Agua Caliente Nova, 1975 (oil on canvas, 40 x 69 inches)

The artist’s dependence on the photograph is one of the defining features of Photorealism. Meisel offers a more specific definition of the style with the following list of criteria (NB: these criteria appear in Meisel’s Introduction to Photo-Realism, cited in the Resources section of this blog):

- The Photo-Realist uses the camera and photograph to gather information.

- The Photo-Realist uses a mechanical or semimechanical means to transfer the information to the canvas.

- The Photo-Realist must have the technical ability to make the finished work appear photographic.

The Photorealist artists were not unified by a central ideology like the artists of the Pop movement, but rather, by their common use of the photograph. Photorealism is therefore viewed as an approach or style, rather than a discrete artistic movement.

7. Robert Bechtle, ’60 T-Bird, 1967-68 (oil on canvas, 72 x 98 ⅞ inches)

7. Robert Bechtle, ’60 T-Bird, 1967-68 (oil on canvas, 72 x 98 ⅞ inches)

As the selection of works depicted thus far suggests, cars are a common subject in Bechtle’s paintings. Like the Pop artists whose work he had seen in England and New York, Bechtle embraced the turn away from Abstract Expressionism in favor of everyday subject matter. His unemotional compositions depict scenes of middle-class life in America––specifically in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he continues to reside.

8. Robert Bechtle, Alameda Gran Torino, 1974 (oil on canvas, 48 x 69 inches)

8. Robert Bechtle, Alameda Gran Torino, 1974 (oil on canvas, 48 x 69 inches)

The frequent appearance of cars in Bechtle’s work is explained, in part, by the artist’s approach to the subject itself. His deadpan aesthetic embraces dry, unidealized reality. Bechtle was interested in exploring banal, everyday imagery, and he cites Jasper Johns as an influence in his fascination with “the invisibility of subject matter [and] painting things that we don’t pay any attention to” (refer to Walker Art Center interview). Bechtle has often referred to the “dumbness” and ordinary quality of the subjects he chooses to paint, as all of the cars depicted in his works are standard models (at least in the context of their time).

9. Robert Bechtle, Sunset Intersection—40th and Vicente, 1989 (oil on canvas, 48 x 69 inches)

9. Robert Bechtle, Sunset Intersection—40th and Vicente, 1989 (oil on canvas, 48 x 69 inches)

Additionally, the car tends to be part of the “natural” background for the artist focusing specifically on the scenery of everyday suburban America; thus the presence of cars in nearly all of Bechtle’s works is both deliberate and incidental. This image provides an example of one of Bechtle’s later works, in which the car is no longer at the center of the composition (a stylistic development) yet remains a key feature of the suburban environment. Further discussion of Bechtle’s ubiquitous car imagery can be found in the ArtsDC.com video.

10. Robert Bechtle, Roses, 1973 (oil on canvas, 60 x 84 inches)

10. Robert Bechtle, Roses, 1973 (oil on canvas, 60 x 84 inches)

The thriving U.S. economy in the late postwar period lead to the proliferation and increased availability of mass-manufactured consumer goods. Just as nearly everyone had access to a TV, other technologies—like the Polaroid camera and automobile—were part of every standard middle-class American home. “Snapshot” photographs were thus a common and familiar item.

11. Jasper Johns, Three Flags, 1958 (encaustic on canvas, 30 ⅞ × 45 ½ inches)

11. Jasper Johns, Three Flags, 1958 (encaustic on canvas, 30 ⅞ × 45 ½ inches)

The people, cars, and streets serve as the content of Bechtle’s paintings, but the primary subjects of his works are ultimately the photographs themselves. Bechtle’s use of personal photographs distinguishes his work from the commercial imagery of Pop art, but he, too, uses an everyday “found” object as his subject—the informal snapshot—akin to Jasper Johns’ appropriation of the American flag.

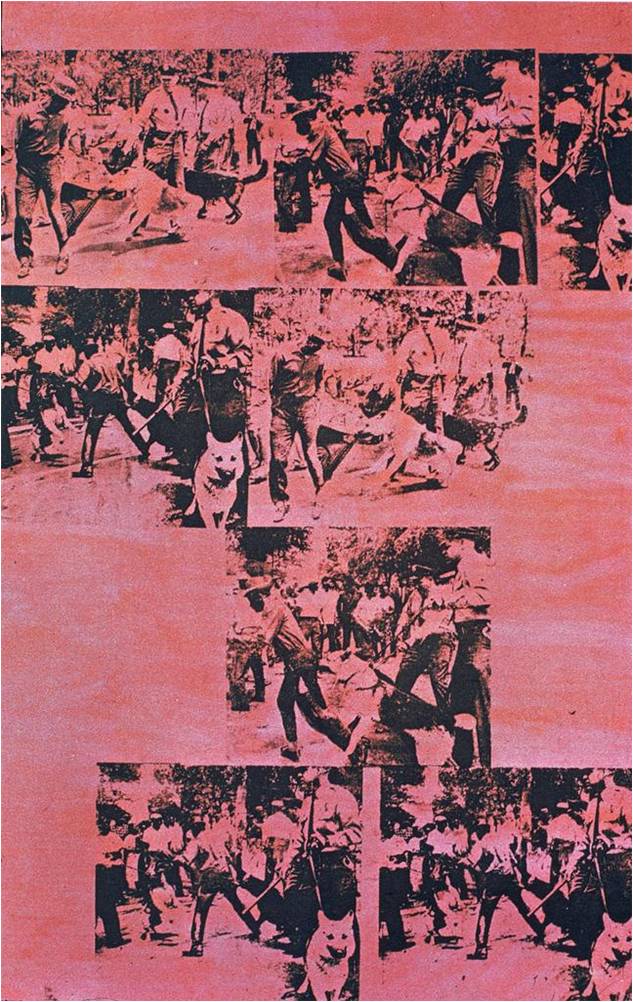

12. Andy Warhol, Red Race Riot, 1963 (silkscreen on canvas, 11 feet 5 inches x 6 feet 10 ½ inches)

Bechtle’s work is not overtly political or seemingly controversial as other contemporary uses of the photograph, such as Andy Warhol’s Red Race Riot, but the work of the Photorealists was nonetheless criticized. Meisel explains, “Even in the extremely liberal atmosphere of the sixties, it was still regarded as cheating or ‘against the rules’ to paint from or use the photograph” (again, from the Introduction to Photo-Realism, cited in the Resources section).

13. Roy Lichtenstein, Little Big Painting, 1965 (oil on canvas, 68 x 80 inches)

13. Roy Lichtenstein, Little Big Painting, 1965 (oil on canvas, 68 x 80 inches)

Like the work of Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, Bechtle’s work combines painting—a tradition associated with “high” culture—with “lowbrow” subject matter; Lichtenstein references the mechanically-printed comic book through his use of Ben Day Dots, while Bechtle employs the photographic snapshot. The process of transferring the image to the canvas in the latter case further emphasizes the mechanical nature of photography and alludes to the reproducibility of the photographic image; some Photorealists use a “grid” system to transfer the image, while others, including Bechtle, project the image directly onto the canvas. This process is demonstrated towards the end of the KQED video.

14. “Time-lapse Video of Robert Bechtle at Work,” SF MoMA

Thus Bechtle’s work functions on two different levels: the hyperrealistic rendering of a photographic image as well as the abstract portrayal of the individuals and objects depicted in the photograph; again, the primary subject of Bechtle’s work is the photograph—not the individuals and objects themselves. Bechtle elaborates on this concept in this video as he notes, “The nature of painting [is] all about shapes and color relationships and flat patches […] It’s really about making marks, not trying to capture subject matter.” The cars and houses in this painting appear realistic, but they can also be understood as abstract forms derived from two-dimensional photographic images.

15. “From the Archive: Peter Schjeldahl: The Story of the Image,” SF MoMA

Art critic Peter Schjeldahl presented this lecture in conjunction with the 2005 retrospective exhibit of Bechtle’s work at the SF MoMA. While the content of the lecture is rather fragmented, Schjeldahl makes some interesting points regarding the banal, everyday subject matter of Bechtle’s work in relation to human memory (towards the end of the lecture in the “Question & Answer” section). Further examination of this artist’s work may not only be pursued in terms of his use of photography, but also in terms of neuroscientific inquiry. Bechtle’s invites the viewer to closely examine the elements of everyday scenes that are typically ignored, and as Schjeldahl’s comments suggest, Photorealist paintings also bring attention to the limitations of memory and that which humans cannot remember.