Thanks to a third year of funding from the Oregon Humanities Center and from the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship of Scholars in Critical Bibliography at Rare Book School (UVA), as well as to support from our co-sponsors, Special Collections and University Archives and the Clark Honors College, we are pleased to announce this year’s roster of exciting talks.

October 5, 2016

Cynthia Herrup (History, USC, emerita)

Why pardons fail

Whenever a presidency draws to its end, we Americans brace for the announcement of the president’s final pardons. We brace and then we complain: should George W Bush have commuted the sentence of Scooter Libby? Was it right for Bill Clinton to pardon financier Marc Rich? Had Gerald Ford promised in advance to pardon Richard Nixon? Pardons are meant to do good —to evoke mercy and to provide a necessary remedy to the sometimes overly harsh application of the law, but it is far easier to name scandals attached to them than wrongs righted. We accept the necessity of pardons but we fret that they are unfair, socially biased and too often products of special access. We don’t lack for critiques of pardoning, but these critiques usually concentrate on the specifics of who gives pardons, who gets pardons, and who benefits from pardons. In this lecture I want to turn in a different direction, to show how the history of pardoning in the early modern era suggests that the problem with pardons lies in the concept of pardoning itself. By looking at the history of pardons in the tumultuous world of seventeenth-century England, we can begin to rethink why we have pardons and whether they can ever do what we expect of them.

January 18, 2017

Evan Gottlieb (English, OSU)

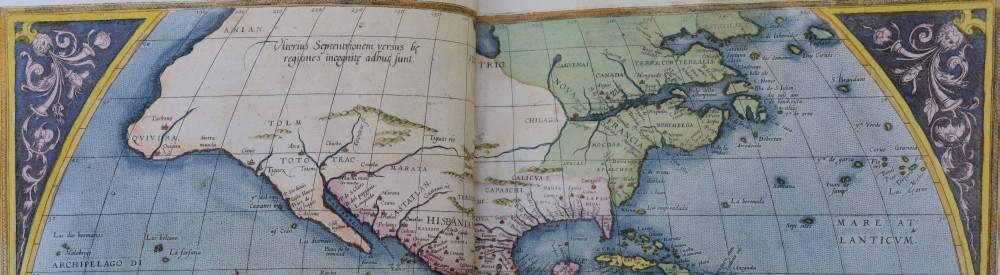

From Here to Utopia: Imagining Better Worlds from the Sixteenth Century to Today

Thomas More was not the first to imagine a world in which peace and plenty had been achieved, but his 1516 book gave this vision its modern name: “utopia.” This word, which More coined, comes from the Latin for “no place” (u-topia), but More was fully aware that his new term also sounded like “good place” (eu-topia). This ambivalence – the best place is by definition one that doesn’t exist – has dogged the concept ever since. How did we get from More’s earnest “good place” to today’s disdain for “utopian thinking”? This talk will consider the modern evolution of utopian thought in Western literature and related arts, looking for clues to help understand the shift from the Renaissance’s faith in the possibility of a better world to today’s pop culture obsession with dystopian visions. One important turning point, I will argue, came during the Romantic Era, when the democratic visions inspired by the French Revolution gave way not only to the Terror and the Napoleonic Wars, but also to a dispiriting conservative backlash following Napoleon’s defeat. Ever since, I will argue, utopian visions have frequently been met or accompanied by skepticism and even cynicism. But with ecological catastrophe looming, can we really afford to give up on imagining a better world?

April 19, 2017

Catherine Labio (English, University of Colorado-Boulder)

An Entirely Reasonable Madness: The Crash of 1720 and the Great Mirror of Folly

1720 was the year of the first international stock market crash. In Paris the value of shares in John Law’s Compagnie des Indes (aka the Mississippi Company) collapsed in the spring. In London the South Sea Bubble burst in the summer. Investors flocked to the Dutch Republic instead. On October 6, 1720, following a riot, the magistrates of Amsterdam forbade further trading in new companies. Within weeks an anonymous consortium of Dutch publishers published the first version of Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid (The Great Mirror of Folly), a compilation of the many texts and images that had been published the previous months on the subject of the windhandel, or trade in wind, code for worthless shares. The highly successful publication helped crystallize the belief that the events of 1720 had been driven by irrational beliefs and behaviors. Economic historians have tried to dispel that myth, but fiction has long trumped fact, in part because of the success and ongoing fame of the Tafereel. What is certain is that the publishers of The Great Mirror of Folly behaved very rationally and profitably when they created this monument to financial folly. In the process, they also enshrined some of the metaphors and images that have been used for almost three hundred years to make sense of stock market crashes.

All events begin at 4:45 p.m in the Browsing Room, UO Knight Library, 1501 Kincaid Street, Eugene, Oregon

SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR COSPONSORS:

Special Collections and University Archives, the Oregon Humanities Center, the Robert D. Clark Honors College, and the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship of Scholars in Critical Bibliography at Rare Book School (UVA).

ORBI is a research interest group of the Oregon Humanities Center co-organized by Elizabeth Bohls, Vera Keller, and Gordon Sayre.