Alisa Freedman (alisaf@uoregon.edu)

Associate Professor of Japanese Literature and Film

Using a comparative approach that focuses on Japan and the United States, one strand of my research and teaching explores how digital media is shaping publishing trends, engendering languages, forming communities of readers, and changing notions of literature. Perhaps more than in any other nation, access to the Internet and developments in computer and mobile technologies have influenced cultural production in Japan and have given rise to a new form of superpower based on the spread of popular trends.

New technologies have both blurred and cemented the boundaries between artistic genres and between readers and authors, raising questions about marketing, ownership, and copyrights. Japanese stories made possible by digital culture are inspiring younger generations’ world views and impacting upon international relations. Below I will discuss some online resources we use in my courses to explore how Internet and mobile technologies affect the creation, consumption, and circulation of stories. As texts change in the digital age, so do the ways that we study and teach them.

For example, we analyze how Japanese cellphones have changed the ways that people communicate, giving rise to new digital languages and literatures. Japanese cellphones have been on the vanguard of global trends, such as text messaging (Short Message Service, SMS) and emoticons. Japanese cellphones have had more uses than those in other countries, due to the provider system and technological developments, as well as the fact that installing landlines has been extremely expensive. In class, we analyzes how SMS altered customs of formal written communication, which has historically relied on set seasonal greetings and “mahō no kotoba,” magically polite words, to soothe social relationships. Abbreviations and visual languages have developed to save space and convey feelings but have demanded communal knowledge to be understood. For example, SKY, for Supā Kūki Yomanai, meaning “super clueless,” was popular SMS slang in 2007. Japanese kaomoji, or “face characters” are horizontal while American “smileys” are vertical, in part because Japanese writing has historically been written from left to right, up to down. Digital culture has promoted horizontal writing in Japan.

Kurita Shigetaka, the “Father of Emoji”

The first emoji (literally, picture characters) was a heart mark on the “Pocket Bell” pager in 1995. Colorful, sometimes animated, emoji were created around 1999 by NTT designer Kurita Shigetaka and have been preprogrammed into cellphones, differing slightly according to provider. The yellow faces, holiday symbols, and other now iconic emoji, are part of Japanese “kawaii” (cute premised on seeming vulnerable) aesthetics, characterized by big heads, missing noses or mouths, and large eyes to show emotion. A standard set of emoji has globalized on iPhones, Windows phones, Skype, Facebook and other platforms, while including images like the bowing man and masked sick face that require knowledge of Japanese society to be understood.

A fun website on cultural misunderstandings of Japanese emoji: http://www.buzzfeed.com/hillarylevine/emoji-explained-by-clueless-adults#.whOXjMNn8

For recent developments in global use of emoji:

http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/best-of-2014-the-year-in-emojis

The Line mobile application (started by a Japanese company based in Korea in 2011 and Japan’s largest social network in 2013) has promoted the use of “stickers,” large-size emoji depicting original and famous characters.

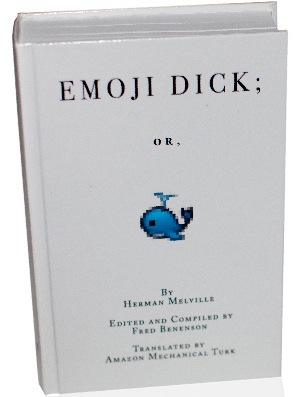

My classes analyze how emoji and kaomoji have changed interpersonal communication and social relationships. We speculate on their use in literature. For example, we analyzed the literary qualities gained and lost by rendering novels in emoji, as evidenced in the crowd-sourced Emoji Dick (based on Melville’s Moby-Dick). To better understand the challenges, we wrote and translated stories. Pictured below is UO student Kathryn Lovett’s translation of the first line of a famous nineteenth-century novel. Can you guess which one?

My classes analyze how emoji and kaomoji have changed interpersonal communication and social relationships. We speculate on their use in literature. For example, we analyzed the literary qualities gained and lost by rendering novels in emoji, as evidenced in the crowd-sourced Emoji Dick (based on Melville’s Moby-Dick). To better understand the challenges, we wrote and translated stories. Pictured below is UO student Kathryn Lovett’s translation of the first line of a famous nineteenth-century novel. Can you guess which one?

New book forms made possible by digital media include novels written to be read on cellphones (keitai shōsetsu) and novels collectively written on large Internet forums. In both cases, although the stories were available for free online, the officially published book versions sold millions of copies, showing the continued endurance of print media. Both forms were especially popular in Japan between 2005 and 2007, pivotal years in the spread of the Internet (i.e. Facebook and Youtube went public around 2005) and the globalization of Japanese popular culture. Both forms grabbed the attention of the international press and were adapted into television dramas and feature films, among other media, and inspired sequels and spin-offs. (Cross-media promotion has long been a dominant marketing trend in Japan.)

Magic Island Cellphone Novel (Keitai Shōsetsu) Website Screen Shot. In 2007, Magic Island had around 5 million registered users.

Deep Love: Ayu’s Story

The trend for new novels available for cellphone serialization began in 2000 with Deep Love: Ayu’s Story (Deep Love – Ayu no monogatari) written by a 30-something man under the penname Yoshi, who opened Zavn.net, a website for cellphone access, to publicize his original works. Deep Love, the story of the decline of Ayu, a 17-year-old who engages in enjo kōsai compensating dating, an issue widely discussed in the mass media at the time, was first available only to Zavn.net subscribers but was later picked up by a major publishing company. The novel became a bestseller, spawning sequels, manga series, television dramas, and live action films.

The best-known website for circulating cellphone novels has been Magic Island (Mahō no i-rando, “i” in “island” a pun for i-Mode digital services), opened as a homepage provider in 1999, preceding the launch of Japan’s local Amazon bookseller (Amazon.co.jp) by one year. Starting in 2000, Magic Island included a “book function” (BOOK kinō) enabling users to write stories in 1,000-character chapters, up to 500 pages, for free. The first Magic Island novel published as a print book was What the Angels Gave Me (Tenshi ga kureta mono, Starts Publishing, 2005) by Chaco, who became one of the most prolific cellphone novelists. In 2004, the Japanese provider DoCoMo began offering unlimited domestic text messaging in their monthly packet plans, a change that made the writing of novels on cellphones more economically feasible.

-Keitai shōsetsu are nicely explained on the English cellphone novel site Textnovel http://www.textnovel.com/keitai

-A fan-translated excerpt of the bestselling 2007 keitai shōsetsu Love Sky (Koizora) can be found at http://www.themillionsblog.com/2008/01/big-in-japan-cellphone-novel-for-you.html

Train Man (Densha Otoko) Internet Novel

The most popular Internet novel has been Train Man (Densha otoko), which, in 2005, became bestselling book written in the format of website posts in 2005, a film, television series, stage play, four manga, and even an adult video. An inspiring love story of an awkward nerd (otaku) and a fashionable workingwoman based on a supposedly real event, Train Man was created through anonymous posts on the expansive 2channel from March to May 2004 and reads like a dating guide to Tokyo. (Founded in 1999 by Nishimura Hiroyuki, 2channel is Japan’s most influential textboard and is comprised of more than 600 forums a wide range of topics.) The story centers on the couple and the online community who encouraged them.

Along with text messages written in slang created on 2-channel, subscribers posted ASCII artwork, both “kaomoji” and elaborate pictures comprised of letters, punctuation marks, and other printable characters. For the print book, the collective author was given the name Nakano Hitori, a pun for “one among us.” The real identity of Train Man remains unknown. In addition to changing notions of books and furthering the marketing trend of cross-media promotion, Train Man encouraged debates in the mass media about Japanese men and marriage during a time of national concern over falling birthrates.

Although the trend has died out, cellphone novels and Internet novels provided models for later commercialization of fan-produced culture. They exemplified what were becoming conventions of Japanese Internet use, including access patterns, visual languages, user identifications, and corporate tie-ins. At the same time, they encouraged public discussions about groups on the fringes of Japanese society, particularly delinquent girls and male otaku.

(Interested in learning some Japanese Internet Slang? Check out 2-Channel English Portal http://4-ch.net/2chportal/)

Other digital stories we study include both legal and unlicensed fan creations, from fanfiction and AMV (animated music videos) to manga scanlations (amateur scanning of manga pages and translation of speech bubbles) and anime fansubs.

(Winning AMV from the Nan Desu Kan anime convention can be accessed at http://ndkdenver.org/forum/index.php/topic,8666.0.html)

I argue that is important for teachers to make students aware of how they appropriate Japanese trends and resist copyrights to fully understand the role of the Internet in the globalization of culture. We also explore how digital media has changed the ways books are marketed. Favorite class activities include evaluating book trailers and designing book covers. These forms provide further insight into how digital media has shaped the creation, circulation, and consumption of stories.

______________________________________________________________

Are you a UO faculty member interested in getting involved with NMCC and/or being our next Prof Picks feature? Please contact us.

Are you a UO faculty member interested in getting involved with NMCC and/or being our next Prof Picks feature? Please contact us.