We visited Teposcolula in week 2 of the 2014 summer program with Dr. van Doesburg, primarily with the intention of learning about archives and manuscripts. We probably will not visit this town in 2015, but you are encouraged to take a weekend day and visit Teposcolula if you are interested. It has a number of fascinating historical sites.

Here is an aerial map of the town, which is part of a paper about the colonial architecture of the town as a fusion of European and indigenous ideologies. The focus of the article is the Casa de la Cacica (House of the Indigenous Lady). It is a remarkable building, so rare today in Mesoamerica, because it provides a sense of the nature of pre-Columbian palaces, with their substantial lintel over the door and their symbols of preciosity (simulated “chalchihuites,” or jade stones) around the top perimeter (of the type we see in codices). Here is an image of the house as it was before a recent restoration; and here is the nearly finished restoration that was financed by the Alfredo Harp Helú Foundation, which similarly restored the San Pablo cultural center where we are having our classes.

Casa de la Cacica (restored sixteenth-century house of a noble indigenous family), Teposcolula. (S. Wood, 2009)

Detail of the circular symbols of preciosity and nobility in the house of the Cacica. Teposcolula. (S. Wood, 2009)

The ex-Dominican monastery in Teposcolula is remarkable for its huge “open chapel” elements, which were an innovation in European church architecture that accommodated indigenous outdoor ceremonialism. Mixtecs, like many Mesoamerican peoples, had carried out many of their religious observations and rituals in the open air. The large atrium that was served by the open chapels also allowed for continuity in this type of practice. It is another example of how Europeans adjusted to Native ways to some extent.

The former monastery has been restored also by the Alfredo Harp Helú Foundation.

The museum in the ex-convento of Teposcolula used to have a wonderful exhibition about both archaeological finds and ethnohistorical research about the Mixteca that was taken down, unfortunately. But we have some images and texts that we have been able to preserve, which we present here in case this information might be useful in curricular development. Here, we wish to recognize the work of Ronald Spores, Laura Diego Luna, Fernando Padilla, and Areli Gutiérrez on this exhibition.

Creation

The following image is a detail from the Vindobonensis Codex that shows how the Mixtec life cycle was initiated in primordial times. Various documents speak of the birth of the first human beings in this region as emerging from the Ahuehuete trees in Apoala.

Eight Deer

The Codex Nuttall features an early Mixtec ruler who was allied with the important city-state of Cholula in Central Mexico. Cholula was a sacred site with considerable prestige, and a connection to Cholula gave the early Mixtec leaders legitimacy. The best known among these early leaders is Eight Deer, also called Jaguar Claw, who received the status of “Toltec” governor in Cholula by means of a perforation of his nose (ritual bloodletting), as shown below.

Town Founding

The image below shows a codex scene of indigenous town-founding activities. According to an early Spanish chronicler, such events would include a measuring cord, carved stones, foundations for the altars and stairways, and [temple] construction could take the form of a “pyramid.”

Local Governance

The next image is a page from the Acatlán Codex, an elite Mixtec manuscript that shows royal couples. In this fragment we see the first governing couples of the community of Acatlán. Such memories were preserved well into the Spanish colonial period, and descendants of these families continued to have an important role in local governance.

Codex Bodley: Marital Alliances

Codices such as this one (Codex Bodley) clearly show the matrimonial alliances between different yuhuitayu (city-states or pueblos). The marriages are represented with the couple sitting facing one another on platforms and woven mats, and nearby are the names of their communities written in glyphs.

Indigenous and Spanish Authorities

The following document, from Tilantongo, shows traditional authority, with the heir of the yuhuitayu seated above a glyph that represents Tilangongo, the new Mixteca authority (the governor wearing shoes), and the Spanish authority (a Spanish judge sitting on a chair).

Photograph of a photo of the manuscript on display in a temporary exhibit in Teposcolula. (S. Wood, 2010)

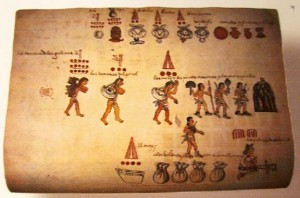

Carriers / Tamemes

Below we see a page from the Kingsborough Codex showing a group of carriers (tamemes) guided by merchants, transporting products such as maize, cochineal, birds, plumes, ceramics, cloth, salt, and chiles. Number glyphs indicate the considerable numbers of tamemes these few men represent. The man in the middle has a number glyph indicating 3 x 400, and the gloss mentions 1,200. See our exercise on deciphering Nahua counting glyphs. Here’s a link to a larger, clearer image of this page.

Agriculture

Probably the largest sector of the population in pre-Columbian and Spanish colonial times in Mesoamerica devoted itself to agriculture. In this image below we see a stylized representation of a man with his digging stick approaching the cornfield. The eight dots in the upper right corner of the scene suggest eight days of foretold labor. Note the flowering maize stalks and the snake among them. This has associations with continued life.

Mixtec Material Culture

The codices, or pictorial manuscripts, from the Mixtec region include representations of many objects of local significance. In the scene below we seen an assemblage of items of material culture that includes tied boxes that contained textiles and paper (lower right). We also see pots (lower left), textiles, tools for combing, painting, recording, magueyes for making ixtle fiber items (upper right), and beverages such as pulque and chocolate (upper left). This collection of items was presented as a religious offering.

Quetzalcoatl Temple

Below we see a representation of a Mixtec temple dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, taken from the Zouche-Nuttall codex. The sacred bundle pertaining to the deity can be seen resting to the left of the top of the stairway. Note the Mitla-like geometric patterns at the base of the temple.

Mediated Christianity

The stone carving below serves as a symbol of the meeting of indigenous and Spanish colonial iconography. At the center is a pre-Hispanic motif identified with two native halucinogenic plants that were important in ritual activities. Surrounding that are a cord and a star with points in the shape of a flor de lis, the latter an emblem of the Dominican religious order and associated historically with Western civilization and European monarchies. The disk is made from a soft stone and comes from the excavations of the chapel built in the pueblo viejo, Yucundaa, on the hill above Teposcolula. Early colonial period, 1521 to 1600 C.E.