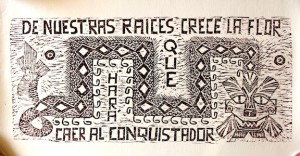

“From Our Roots Grows the Flower that Will Make the Conqueror Fall,” graphic art by Mojo, Oaxacan artist. (Photo, R. Haskett, 2014)

This piece (above), by Oaxacan artist “Mojo,” emphasizes how the power of the conqueror can be undermined through pride and cultural florescence. Oaxaca is certainly a place where communities are working hard to preserve culture and revive endangered languages in the twenty-first century.

Bartolomé de las Casas

Interestingly, some of the strongest and longest-lived protests about the Spanish colonial enterprise have come from inside the European camp. Historian Friedrich Katz (in Riot, Rebellion, and Revolution, 1988) sees Spanish officials and clerics as a force that moderated the impact of independent Spanish colonists. Settler-colonists were more likely out to advance their own interests at the expense of indigenous communities. He writes: “the crown and the church, because of their efforts to control the hacendados and the encomenderos, acquired legitimacy in many Indians’ eyes. For a long time, this legitimacy constituted a powerful deterrent to any serious attack [by indigenous communities] on the Spanish colonial system.”

Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas participated in a number of conquering expeditions, so he saw first-hand what they could entail. As a classic reward for participating in such expeditions, he was given an encomienda grant, which was the right to extract indigenous labor. Gradually, however, and possibly through his witnessing of colonists’ excesses, his views turned against certain elements of the colonial enterprise. He was perhaps the first priest ordained in the Americas, and he would eventually become a bishop, evangelizing the Maya most actively. He also became a passionate reformer, lobbying the king in Spain to insist that indigenous people have more protection. Partly as a result of his input, the New Laws of the Indies were instituted in 1542, and the gradual demise of the encomienda began. But its eventual replacement, the hacienda system, may have been worse.

Las Casas is partly famous for his debate in Valladolid, Spain, in 1550 with with Juan Inés de Sepulveda, about whether indigenous people were “men or monkeys, whether they were mere brutes or capable of rational thought, and whether or not God intended them to be permanent slaves of their European overlords.” (From: Marilyn Lutzker, Multiculturalism in the College Curriculum, 1995, 54.) It is hard even to imagine that conversation being anything other than ridiculous, but it gives us a window onto a mindset from that period.

Las Casas’ arguments against Spanish colonialism were seized upon by the British, who were fierce competitors in colonizing the America. They used his critiques to paint what is called the Black Legend of Spanish colonialism, which presented it as excessively cruel in comparison with other colonial approaches. To say that this was overdrawn is not to apologize for imperialism of any sort, but to ask that we take a closer look at the evidence and compare imperialistic methods.

Deterrents to Unified Resistance

Colonization has deep roots in Mesoamerica. Many communities faced colonization by other indigenous groups over the centuries prior to the invasions by Europeans. Then, of course, beginning in 1518–19 they would respond to the Spanish invasion and the launch of Spain’s colonization effort. On this page, we will gather materials that emphasize ways indigenous communities resisted—responding through active and more subtle forms of resistance to intrusions and efforts by outsiders to get them to change their ways.

As Historian William B. Taylor expressed in his book, Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages (1979), indigenous communities tended not to band together to resist intrusions but, rather, responded with rioting and small-scale uprisings when local conditions became impossible for them. In his book, The Nahuas (1992), historian James Lockhart emphasizes how the micro-patriotism inherent in the independent socio-political entities or ethnic states, such as the altepetl, discouraged indigenous people from seeing themselves as united with their neighbors; it undermined pan-Indian unification, which would be required for large-scale armed resistance.

One can imagine that fierce independence and community focus also ensured cultural survival to some extent; but these were not really “closed” communities. Eric Wolf was a scholar famous for theorizing about “closed corporate peasant communities.” But his assessment was an exaggeration that was not borne out by archival research into real life on the ground. Indigenous communities always traded with other communities, individuals moved around a lot, and many had marriage partners across communities. But they nevertheless maintained a ethnic identity that was rooted above all in their own community. Lockhart called this a micropatriotism.

Colonial Uprisings

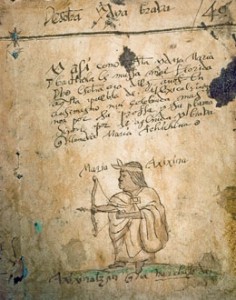

There were some exceptions to the rule. A central-Mexican, sixteenth-century resistance movement is described in the possibly apocryphal Codex Cardona. In it, resistance efforts were led by a María Achichina (also spelled Axixina), who organized and armed people, only to be arrested by Spanish authorities and then hanged.

A portrait of María Achichina in the Codex Cardona, possibly a late-colonial manuscript in private hands.

Lawsuits

Indigenous communities fought hard to defend their territories, especially at the local level, over the entire Spanish colonial period (1521–1821). They sought the application of a law that guaranteed them a minimal land base, not just for the housing core but also for farming. As the native population recuperated from the devastating waves of epidemics, which reduced numbers by up to 90% in some places, and after much territory had already changed hands and served as the basis for many Spanish-owned haciendas, indigenous communities were especially active in the late seventeenth century. The “six hundred varas” of the minimum town site were measured out in the four cardinal directions from the center of town after 1695, and then squared off.

Litigation between individuals—Spanish and indigenous— was prominent, too, from the sixteenth century forward. One María Quetzalcocoztli, a resident of San Hipólito Chimalpan, Ocotelulco, in what became the state of Tlaxcala, was quoted as staying “yn tla quinequiz no yolo uel justicia,” or, “lo que quiere mi corazón es mucha justicia” (what my heart yearns for is great justice). This is from the Catálogo de documentos escritos en Náhuatl, siglo XVI, v. 1, p. 27.

Twentieth-Century Anti-Imperialist Sentiment

Mexican murals of the twentieth century, such as we see in the work of Diego Rivera, below, explored the theme of indignation surrounding Spanish conquest and colonization.

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution exploded in 1910 and lasted a number of years (some say it ended in 1919 with the assassination of Emiliano Zapata). While it had many factions and various ideologies, one sector, led by Emiliano Zapata was in favor of breaking up the large landed estates and redistributing the land to the people who worked it. This was the most appealing to those who were concerned about the dispossession of the rural small holders and landless estate laborers. This idea had the potential of benefiting indigenous communities. This helps us understand how images of Zapata are linked to resistance. Zapata was also known to make pronouncements in Nahuatl.

The role of women in the Mexican Revolution is a topic that captures the imagination of people interested in resistance, too. Here is a link to PBS curricular materials about Mexican women in revolution.

Twenty-first Century Resistance

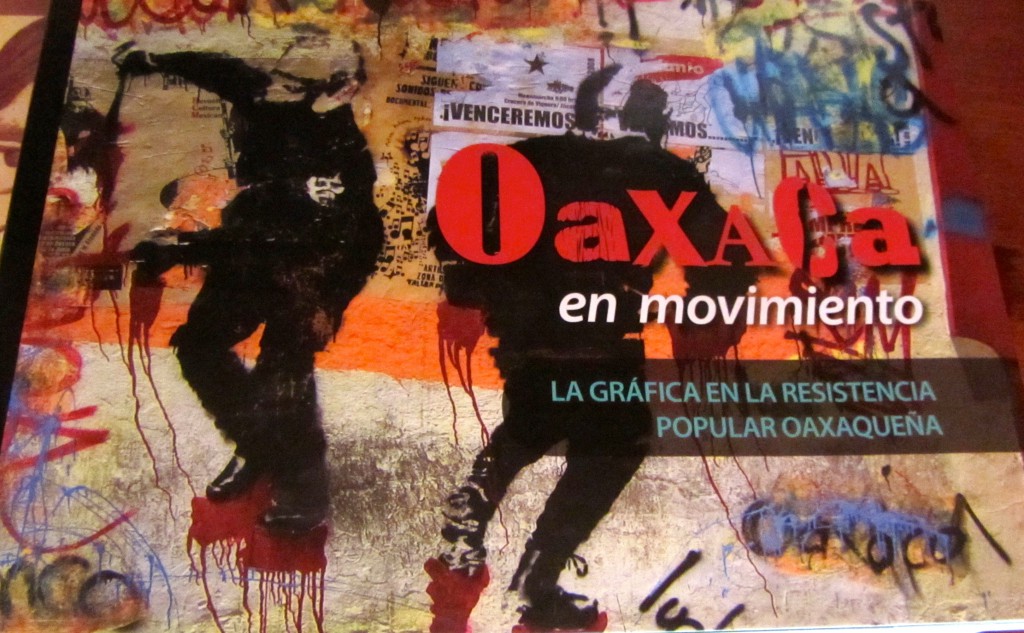

The teachers movement of 2006 in Oaxaca, Mexico, included many teachers from indigenous communities as well as their sympathizers. Their issues were wide-ranging, but improving conditions for the education of indigenous youth is a clear goal. Most of the teachers’ demands remain unmet, and the occupation of the zócalo, marches, and roadblocks were constants in Oaxacan daily life for a couple of years. Our urban art/protest art/graffiti page helps illuminate this type of resistance to the inequality of the status quo. Below is an example of a potentially illuminating book on this topic available for sale in 2014 in the Grañén Porrúa bookstore on Macedonio Alcalá (next to Café Brújula).

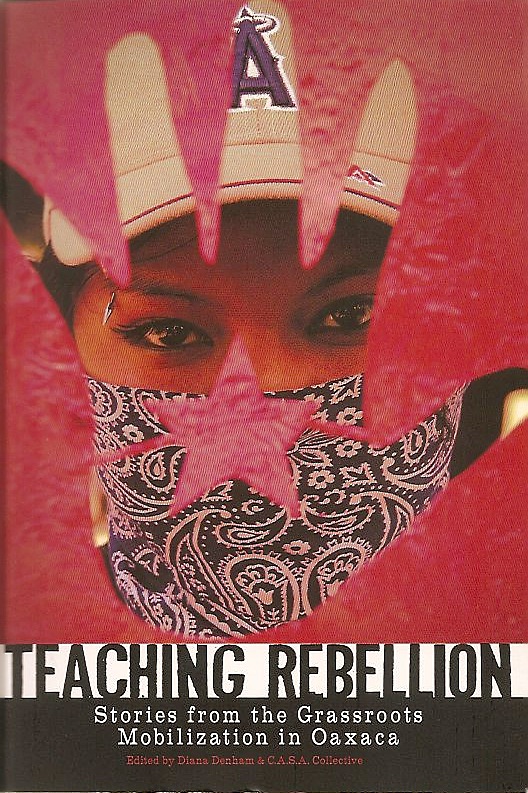

Another much-acclaimed book is Teaching Rebellion, a compilation of stories from participants, including indigenous community activists among many others, in the Popular Assembly of the People of Oaxaca (APPO) in the 2006 social movement. Economical copies of this book can be purchased on line, including some very clean, used copies.