Here we are assembling materials that might help with curricular design relating to the Mesoamerican ballgame across time. Archaeological sites and artifacts taken from such sites (not usually found in museums) provide physical remains helpful for understanding the game (or games, really, for it varied regionally) in ancient times. Mesoamerican ballgames have been revived in recent times, and have possibly had continuous play in some remote places.

Pre-Columbian Ballgames in Mesoamerica

Please visit the wonderful interactive website, “The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame,” as a starting point for understanding the game (which had many variations) in pre-contact times.

Justin Kerr’s Mayavase Database

Classic Period Maya vases have many scenes that relate to the ballgame. We have permission to use any of Justin Kerr’s photos of Maya vases. If you go to his database search page, you can search ball and other terms and get many results. One recurring feature is the kneeling position of some ball players. This can be a give-away when you view figurines in museum who represent ball players.

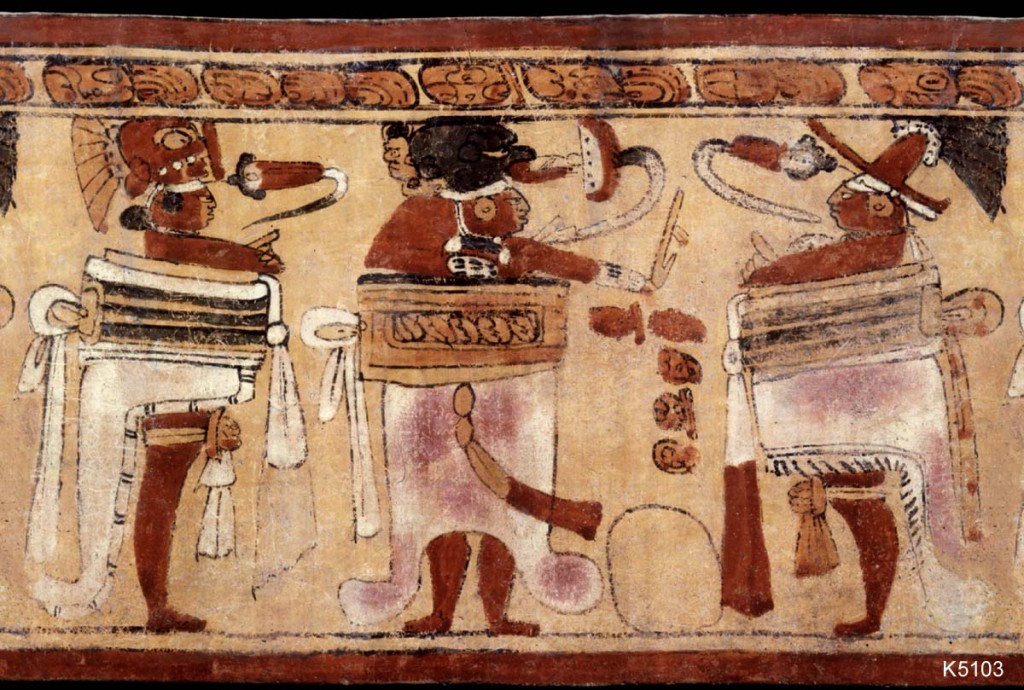

Here are some examples of the Maya vase art about the ballgame:

Game action in a Maya ball court. Note the large, black rubber ball at the center. The kneeling figure wears a jaguar skin. We see standing feather fans on either side of the play. You will see stepped buildings surrounding remaining ball courts yet today in the Oaxaca region (as elsewhere). K1209. (Photo, Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with his permission.)

Classic-Period Maya vase scene with many ballgame players. The kneeling pose in the center, is common. Note the clothing the players wear (blankets?) and their designs, as well as the headdresses that resemble animals. Glyphic texts explain some of what we are seeing. K1871 (Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with his permission.)

Ballgame. Men wearing three ridged yokes and knee pads. Two players wear monster mask headdresses. The third player wears a black bird headdress. The black rubber ball is extremely large here. K4407. (Justin Kerr Mayavase Database with his permission.)

A wooden yoke, much as the ones seen here worn on the chests of the players, was excavated at the Classic Maya site, Tikal. K5103. Museums are full of carved stone yokes, which seem to be too heavy to have been worn in actual games; they may have been used in ceremonies. (Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with his permission.)

The work done by Justin Kerr, in photographing and making accessible dozens of images of the Maya ballgame, has led to some re-thinking of how the game was played. Please see Michael Coe’s article (free, full-text), “Another Look at the Maya Ballgame,” (2003). And “The Royal Ball Game of the Ancient Maya: An Epigrapher’s View,” by Alexandre Tokovinine (n.d.), another free, full-text article. This one also includes references to sources about the Aztec ball game. Also, check out this video of a lecture (only in Spanish) by Ramzy R. Barrois, “El juego de pelota maya,” hosted by the Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala, from 2008 (58 minutes).

Images from Codices

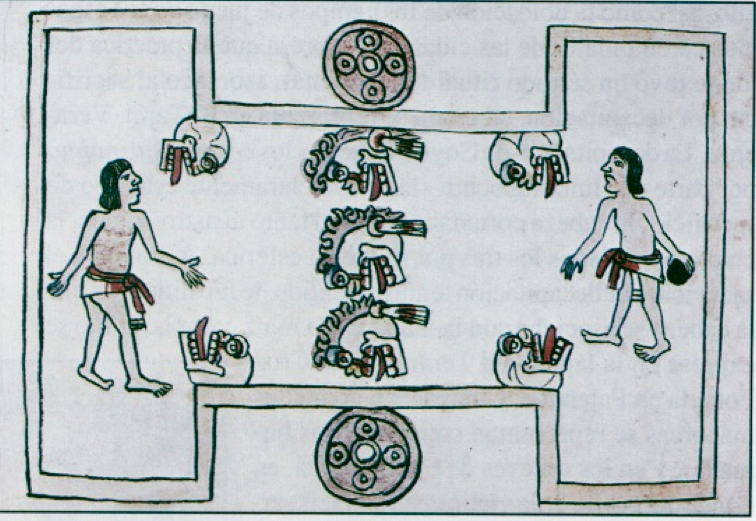

We can see some interesting details about the pre-Columbian ballgame (or at least early colonial) in sixteenth-century codices. Below, we find an image from the Codex Magliabecchiano.

Folio 80 recto, Codex Magliabecchiano, showing the classic ball court, two players, carved rings on the sides, and seven heads of sacrificial victims.

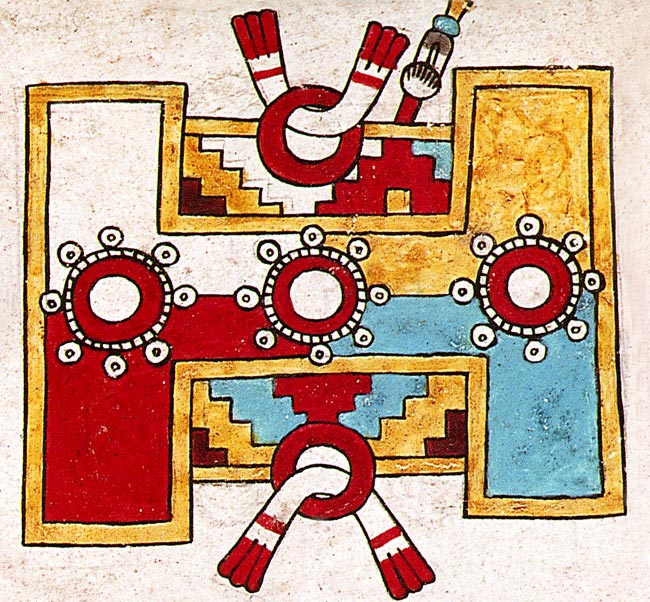

Next, we see a detail from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall. This is an accordion-folded, pre-Columbian document of Mixtec pictography, currently held by the British Museum. The codex derives its name from Zelia Nuttall, who first published it in 1902, and Baroness Zouche, who donated it to the British Museum.

Here is another detail of a ball court from the same codex, the Zouche-Nuttall, as published by Mexicolore.

Codex Zouche Nuttall, detail of a ball court. Note the geometrics, somewhat reminiscent of Mitla architectural friezes. From Mexicolore.

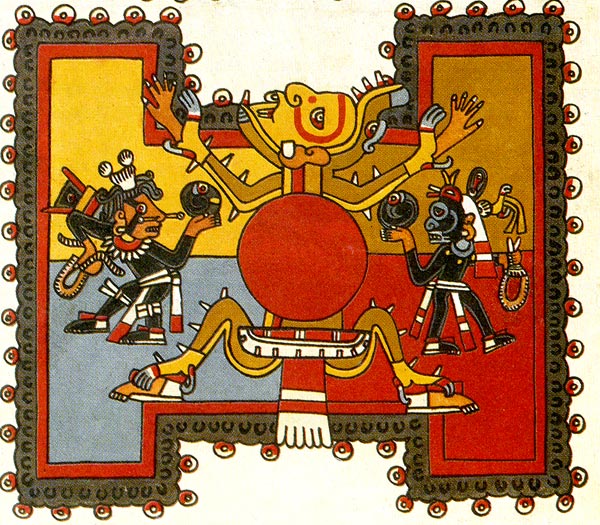

Below we have another detail of a ball court, this one from the Codex Borgia, also likely pre-Columbian in origin and with Mixtec-Puebla associations. This manuscript is currently held by the Vatican library and is named for its donor, the Cardinal Stefano Borgia.

Codex Borgia, detail of a ball court and players. From Mexicolore.

And another image, below, from the Codex Borgia (folio 45) shows players holding batons in the four corners of the court. This court has rings on the sides once again. The symbols around the perimeter are similar in both Borgia ball courts. Is that cultivated land (brown with u-shaped symbols) and stars (red and white circles within circles)? See this image of a star gazer in the Codex Mendoza. And milli glyph elements also from the Codex Mendoza.

Codex Borgia, detail of ball court, folio 45. Referenced in Wikipedia.

Ball Courts in Archaeology

A great many ball courts can still be found in the archaeological sites of Mesoamerica and beyond. Some type of ballgame was played in the Caribbean islands, too. Please take note of the courts we will be seeing in Monte Albán and Atzompa. The classic shape is a capital letter I. The number and placement of these courts is a testimony to their significant place in the city core, adjacent to palaces and temples.

Below we see what remains of the ball court at Yucundaa, in the Mixteca Alta. This was excavated and then had to be filled in again until a later date when it might be opened to the public.

Stone carving of the head of a ball player with a protective mask decorated with animal fangs, Monte Albán (R. Haskett, 2005)

Ball Game in Pre-Columbian Pottery

Late Pre-Classic ceramic representation of a ballgame from Nayarit (Western Mexico). Museo Rufino Tamayo. (S. Wood, 2010)

Ceramic depictions of the ballgame (however it might have been played in what is now West Mexico) are wonderful for what they convey of daily life and family enjoyment. Notice how the people have their arms around one another.

Looking down upon the game. Same ceramic piece from late Pre-Classic Nayarit. Museo Rufino Tamayo. (S. Wood, 2010)

Note the gear around the players’ waists (loincloths? yokes?) and their headgear. People in the audience (just fans? or some of them waiting their turn to play?) have something similar on their heads.

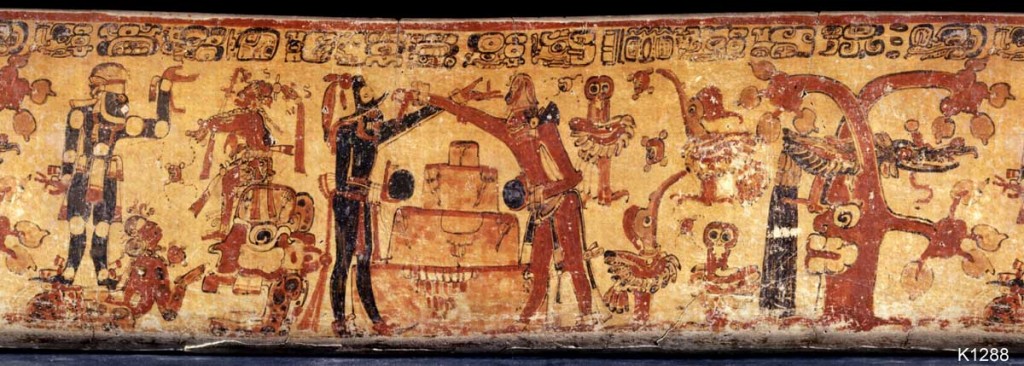

The Ball Game in Foundation Stories

A ball game is a major feature of the colonial Quiché (also spelled K’iche’) foundation document called the Popol Vuh, which is an impressive narrative from pre-contact times. The narrative features two figures, called Hero Twins, who are named Hunahpu and Xbalanque in the Quiché language. Classic Maya art (200–900 C.E.) appears to include what may be these same Hero Twins; if so, this would constitute a considerable longevity for the narrative. The twins may represent mythical ancestors to the Maya ruling lineages across time. Similar to their father and their uncle, the twins were were ball players. The legend states that their father and uncle were defeated in a ball game played against Lords of the Underworld, who sacrificed them. Then the Hero Twins avenged the deaths by defeating those Lords in a later ball game. The Hero Twins also turned their half brothers into howler monkey deities; these were patron gods for artists and scribes. Hence, monkeys are often seen in association with art representing the ballgame.

Ballgame with Hun Hunahpú and the journey to Xibalba (Popol Vuh ballgame connection). K1288. (Photo, Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with his permission.)

Research into the Rubber Ball

Note the size and the black color of the rubber balls that the Mayas used (in the various Maya vase images above). Some of the balls appear to have been huge. The size of the ball is also discussed in Michael Coe’s essay from 2003.

Researchers at MIT have been taking a close look at the processing of rubber more than 3,000 years ago, as reported in this article, “A Good Many Years before Goodyear.” (MIT News, 2010)

Research on the rubber ball of the Maya is described in this YouTube video of 2+ minutes. A massive number were sent to pre-Columbian Mexico City as tribute items. The approximately 50 surviving pre-Hispanic rubber balls have largely been excavated from natural wells in sandstone in the Yucatán called cenotes. They would have been thrown into the cenotes as religious “offerings.” Another short video piece on YouTube, “Exploring the Mayan Ball Game on Museum Secrets,” is 41 seconds.

La Pelota Mixteca/Zapoteca Today

The Mixtec/Zapotec Ballgame of pre-Columbian times has evolved but is still played today both within the region of Oaxaca and abroad, such as in Fresno, California, where many migrants from Oaxaca now reside. We will have a guest speaker whose father and grandfather play one of many versions of the game, and we will see some of the balls and mitts. We also hope to take an excursion to see a game in action.

Ballgame in Street Art Today

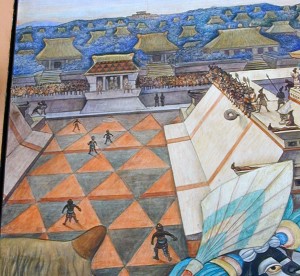

Dramatization of the ballgame in street art in Oaxaca today. Beta / ASARO. (Photo. Itandehui F. Ortiz, 2009)

Readings

- Varinia del Angel and Gabriela León, Juego de Pelota Mixteca/The Mixteca Ball Game (2006; 24 pages; see Amazon.com)

Curricula

Elise Weisenbach, High School Spanish or Social Studies

- “The Mesoamerican Ballgame” (Best viewed with Mozilla Firefox)

Lynn Fernandez, High School Spanish, “Juego de Pelota”

- Lesson Plan (DOC, PDF)

- Juego de Pelota Notebook (PDF)

- Juego de Pelota (PPT, PDF)

- Los jeroglíficos y códices (PPT, PDF)

- Juego Game Cards (PDF)

- Codex Example (PDF)