When Willamette Week arts critic, Richard Speer wrote his WW swan song and prepared to vacate his long-held position as arts-man-about-town, First and Last Thursday aficionado, and bastion of the Portland art scene to direct his insight towards several book projects, he first published a list of Portland’s top ten art exhibitions, 2002-2015. His taste and preference was readily apparent in this list—visual extravagance and fantasia reign supreme….and a sort of checklist for Portland’s favored exhibitions during a 13 year period was remarkably established as Speer lauded the extravagant or what “used to be better.” Into this list came the Portland2010 exhibition curated by the one-and-only Cris Moss. It was an extraordinary show, by any means, a “jaw-dropping” group collective with the likes of Shelby Davis and Crystal Schenk, Marne Lucas and Bruce Conkle, among others. And in a list that only includes ten exhibitions for an entire city and for an art critic’s career, as Speer gleefully points out, Portland played host to “146 (Speer-attended) First Thursdays and more than 3,120 exhibitions,” being included is no small feat.

Well done, Mr. Moss.

This same week we also read of Cris Moss in an online forum called PORT. Here there are a few words wrangling with the idea of Moss as a wanted entity…and a brilliant curator, or words to that effect.

And, so we come to the story of Cris Moss, highly sought-after curator, lauded gallery director, himself a multi-media artist who with one simple swipe of a google search engine comes up as something of a fantastic individual, (“Moss’ programming is considered to be some of the most notable in the Portland area”). The University of Oregon’s White Box recently brought on Moss as the new gallery director and curator, or in the words of one Portland arts writer, “the UO likely snagged Moss…” Indeed, perhaps we did, and it was a good move, to be sure. Already Moss is connecting, concocting and devising ways to move forward with the White Box with strategies and plans that would, I imagine, make Richard Speer pause. Speer challenged Portland galleries and gallerists to clarify their missions, focus programming and include local as well as international artists as a way to connect with the Portland populace. Calling for a cross-pollination of arts, dance, music, Speer left us with a sage prediction: the only way to save our city’s arts scene is to infuse it with public interest and active participation.

If Moss continues to rely on his pluck and circumstance, things, undoubtedly, will go well. He has much to call upon to help guide his position at the White Box. Hailing from the remoteness of a Billings, Montana upbringing, Moss remembers as a young child his parents constantly traveling and toting their offspring to historical museums, arts experiences and cultural excursions all over the eastern United States. The family always returned to homebase in Montana which only accentuated the remoteness and isolation to a youthful Moss. Surrounding the family with a plethora of “artist friends,” the Moss family saturated their children in a vibrant atmosphere of arts appreciation and comfort.

But despite a vibrant social exposure to arts and culture and a fairly affluent rural-based life (at those formative years committed only to the pursuit of snowboarding), Moss found the beautiful but desolate environment only propelled and heightened his curiosity and intrigue with what he saw on those frequent family vacations to large cities. His youthful exuberance culminated in his leaving home, he says “running away” at the age of 15, relocating to Seattle, Washington where very briefly he became a homeless kid of the streets. It was rough living for the teenager and Moss recalls eagerly returning to a high school situation in order to complete his education. He attended Garfield High School in Seattle’s Central District and experienced, for the first time, a diverse student body where Moss, as a Caucasian raised in the rural climate of Billings, Montana was now in the minority. He left the school dropping out again. But by his late teens, Moss was enrolled at NOVA high school, an alternative learning experience in Seattle. Here, he thrived taking courses in photography, and surviving on his wages earned working at night for various Seattle restaurants in jobs from dishwasher to lead cook; his mode of transportation, simply, a skateboard.

Eventually, Moss ventured back to Montana to attend University of Montana and turned his attention to a focus on the arts. He enrolled as a non-degree student excelling in his courses in ceramics, environmental studies, probability and statistics, and judo. He found himself immersed in his ceramics studies and entered a competition, NCECA, National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts –a competition his entry won.

Ceramics captivated Moss and he studied toward a BFA from the University of Montana in ceramics. Stopping mid-way through to move to Minneapolis where he worked for a snowboard shop and took classes at the local community college, Moss returned to UM, with the intention to finish his studies, however, friends had migrated to Oregon to Mount Hood and the snowboarding scene in the mid-1990s. Moss followed relocating to Mount Hood and living the life of a snowboarder on the mountain daily. A year later he moved to Portland where he got a job as a bike messenger and enrolled at Portland State University studying photography. From PSU, Moss transferred to Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA) where he worked with and studied ceramics (mostly sculpture) and pursued his growing interest in video, combing the two. He still had plenty of time on the slopes and worked part-time as a lift operator and snowboard instructor to support season passes at Mt Hood.

Moss’ education in the arts quickly took precedence over his snowboarding lifestyle and he ceased boarding competitively to turn his attention to art school. By 2000, Moss had graduated from PNCA with a BFA in general fine arts. He had begun working closely with Portland gallerists and arts leaders, Elizabeth Leach, and (when he had been at PNCA) with Sally Lawrence (PNCA president), Gerry Snyder (PNCA dean) and the Philip Feldman Gallery. It was while working with the gallery directors that Moss was given the opportunity to work directly with the artists. This experience allowed him to learn the formalities of getting work into a gallery and instigated a broad range of connections. His interest in gallery work and representing artists quickly blossomed into the series of Donut Shops Moss opened –the inaugural shop being at 2nd and Alder in the SE Industrial area of Portland.

Moss used his experience and expertise he had learned from teaming with Feldman Gallery and working with artists in the Donut Shop ventures to combine video with sculpture installation and work in new ways with artists on the cutting edge of these technologies. Moss attributes the success of his Donut Shop exhibitions to “not being afraid, just talking to people.”

As his career grew and the success of his collaborations became evident, Moss was carefully formulating his philosophy on working with artists and creating meaningful exhibitions. The turning point came in the early 2000s when his work was written about in Seattle’s The Stranger,

All right, it’s in Portland. But gallery founder and curator Cris Moss is doing something I’ve heard a lot of artists talk about, but never finally do: starting a gallery that changes location with each show. This not only alleviates the ever-present real-estate problem, but also creates the challenge of a changing space. The first show, which concentrates on alternative media, features the work of Moss, Seungho Cho, Cynthia Pachikara, Nan Curtis, and Ginelle Hustrulid. Opening reception Fri Aug 4, 6-9 pm. The Donut Shop, 630 SE Third. Through Aug 18.–The Stranger

In June of 2001 Moss was invited to bring his Donut Shop #4 to the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington in what Moss describes as “[his] career taking a turn…[he] was getting attention in The Stranger..and now Whatcom was offering [him] a budget.” Being offered financial incentive to launch his Donut Shop was a somewhat revolutionary concept in the career of Moss who thus far had existed on the precipice of funding and accomplished most of his installations sans monetary assistance.

Hand in hand with his burgeoning career, Moss was developing a keen sense of how he wanted to work and the best practices in the field—and he was finding himself devoted to the idea that “each artist must be compensated and when there is funding, each artist must receive a cut of the money, a stipend,” he says. This is the Moss Mantra, so to speak, and is key in the support of visual artists —they are not just to be capitalized upon for their work– people need to make a living,” Moss encourages. The early 2000s were a time of Moss focusing on work of others, helping artists begin and maintain careers, and establishing connections with institutions, as he comments, “I had stopped putting my own work in the shows.” This was about to change.

Moss, now back in Portland, wanted to go to graduate school. Within a year he was heading to New York to study at NYU for studio practices and working as the director of the Steinhart Gallery in NYC.

In his first week of graduate school at NYU, Moss enjoyed a prestigious studio in the East Village where he had a pristine view of New York’s Twin Towers….until the fateful September 11. When the towers fell, Moss’ view changed, metaphorically and literally. He became interested in how this event saturated and effected different markets and sought to explore more the use of space, the absence of tangible objects and the presentation of physical entities and the interrelation of objects placed into spaces. Moss continued working with an internship at the Swiss Institute of Contemporary Art where he was involved in cutting edge exhibitions and helped with the installations and assisted the artists individually by brainstorming and “having fun with” the projects. Moss was delving further into his own work ethos and his philosophy on “inviting artists to go crazy with the spaces” was really taking shape. He encouraged the artists he worked with to “push the bounds of what the work is and to explore what [their] next level is…”

This work allowed Moss to realize that his “larger projects are wonderful to develop smaller projects and to let people see [one’s] talent in a different way.” As his curatorial practice flourished, Moss noticed that his “curating was becoming [his] own art practice.” And that his belief in the artist, first and foremost, as a person to be treated with respect and in a fair and considerate transaction-like process of monentary compensation, was surfacing as tantamount to his work practice.

In 2005 Moss was back in Portland, this time a willing-to-put-down-roots father and soon to be the curator at Linfield College’s gallery. He was offered teaching positions at Linfield as well, to instruct students in art and studio classes for digital photography and graphic design, gallery management and curatorial practices.

Ten years passed. And, this winter a career move back to the metropolis of Portland: Moss joined the White Box staff in January 2015. He comes to the University of Oregon with a varied work background where he has learned from his experiences to make good use of his education based in the arts. Addressing his education, he asserts, “it is a degree in problem solving, a degree in which you take your own steps and a degree in which you have to keep your head in what’s going on, build networks, and stay involved. You can’t be afraid, you have to look for your own solutions and promote your own ideas…don’t be afraid.”

Along with his new career at the White Box, Moss is delving into videography projects that began while he was still at Linfield. Paradoxically, and yet another curiousity-inspiring aspect of the Moss career path, he has been the executive director of production and videographer for the Ultimate Cage Fighting (Sportfight) events –filming the fighters in the ring, directing the camera crew and creating commercials for sport cage fighting.

I asked Moss to comment further on his goals for the future and for the White Box and, just for fun, on his dream job. He responded with a mindfully delivered statement punctuated by reason, and experience. His reliance on drawing from an adventuresome and fearless life well-lived and an education grounded firmly in the very essence of what he loves and holds dear stands as evidence of Moss’ genuine dedication to his field, his craft, his art. He practices what he preaches.

The Portland art scene has a long history of supporting contemporary and cutting edge exhibits. With the unique location, non-profit status, and facility (there is nothing that compares to the Gray Box in the region), the White Box stands in a position to build a foundation and reputation that pushes the Portland art scene even farther. By bringing in local, national , and international artists, the WB can promote and challenge some of the preconceived notions of what qualifies as art. The curatorial role of the WB will serve as a platform to make the WB a renowned venue for consistent, quality programming.

Oregon is one of the lowest ranked states for money allocated to the arts. I believe at one time it was the second lowest, it still might be. I am working on building a large enough operating budget that can support artists by not charging them to use the venue and in turn even giving them honorariums. As an institution that promotes and teaches professional art practices we need to treat artists that we work with in a professional manner. It is their profession, we house it, we should support it.

Recent meetings on the main campus in Eugene with the Department of Art and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art have illustrated a desire to forge strong ties between UO Eugene campus and the WB. The individuals that I spoke with share my concept to bridge any gap and are eager to start the process. I would like to initiate a format that brings visiting artists that are exhibiting at the WB to Eugene for artist talks and one-on-one studio visits with both faculty and students, and vice versa, bringing Eugene-planned lectures to Portland. The Schnitzer and WB could collaborate on exhibitions. This format will help in securing funds that allow us to pay traveling expenses and honorariums for the artists. The benefits of quality programming should benefit all of UO.

I’m not sure what my dream job would be. My thoughts change on a regular basis. I think that is good. As the world changes so should our involvement. Although, it would be nice to be a guide for extreme back-country snowboarding. –Cris Moss

Thank you to Cris Moss, for your time and insight.

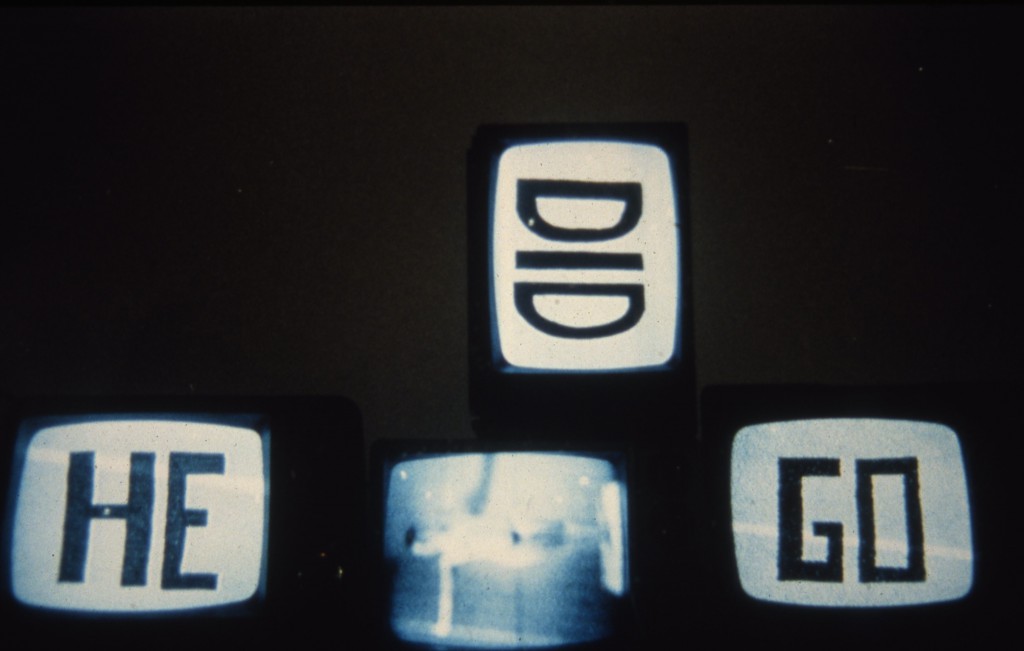

A Selection of Work by Cris Moss….