What If ? . . . . On Intersectionality and Your Visual Backlog

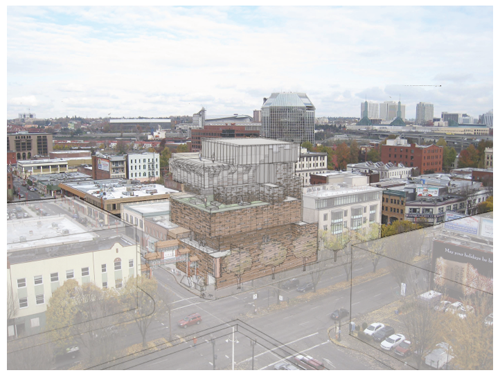

The WHAT IF? TEDxPortland Art & Design Exhibition is a curated collaboration by the University of Oregon and TEDxPortland. 26 artists donated their time, treasure and talent to make this possible. Every penny from the online auction will benefit the Children’s Healing Art Project (CHAP). The Nike Foundation will match the amount raised. The auction starts at 5:30pm on April 17th, ending at 5:30pm on April 27th The exhibit will be housed at the White Box in the White Stag Block from April 4-24th and then will be transported and re-installed for TEDxPortland at the Portland Art Museum on April 27th Celebrating Ideas & Art worth spreading.

In keeping with the mission of TED, the exhibition showcases work that mines the territory between art, design, technology and science in popular culture. The work illuminates natural and imagined worlds through form and function. Selected artists were invited to submit work that is an exploration of visual media that connects to these multiple histories. Responding to concept, object, new knowledge and technologies through creative process, exhibited works span discrete disciplines and burgeoning practices.

Co-curated by White Box manager, Tomas Valladares and Molly Georgetta (Compound Gallery), What If ? presents a diverse yet curiously cohesive body of works that delve into both the digital and the handmade: a sort of vibrant intersectionality. Upon further observation, streams of unity begin to flow through the show but rather than providing simply visual entertainment and explanation, these works united and merged together in this space play with the realness of things and ideas in ways that encourage a captivating uncertainty.

I stared for an unreasonably lengthly amount of time at Zach Yarrington’s signage-cum-art Say it Out Loud. It spoke at me, not to me: playing with the blunt, authentic, familiar, but something was different. A myriad of thoughts flowed, too: 1800s memorabilia, font obsessiveness, decoration with flourish, signage you read at a glance, yet it felt new and unexpected, shifty. Had I seen this before? Heard this before? [Look at Zach Yarrington’s Say it Out Loud]

We’ve all heard that words can be deceiving. And, things are not always as they seem. Objects, images and language can evoke memories, appear commonplace, create difficult or lovely feelings, even prompt new ideas. The work displayed in TEDx’s “What If?” bring together pieces at once provocative, questioning, comfortable and challenging.

Craig Hickman’s “LOVER’S LANE” lassoo’ed me in next. It looked real, it sounded real, it sounded appealing, but then there was that roadsign, grubby billboard delivery, itself lovable in its truthfulness. However, what might have seemed comfortable was challenged by context, materiality, my own memory. Then I saw that wayward apostrophe, and the added comment, “HIGH WATER.” Had I seen those two paired together before? The logic of it was almost taunting, shamefully so–like, well of course, why didn’t I see that coming? Is it difficult to cope with ambiguity and a subconscious awareness? Hickman has no qualms in suggesting that we look, and expose ourselves to his nothing-barred candor. [Look at Craig Hickman’s LOVER’S LANE or for even more, explore his book OXIDE].

The “What If ?” TEDx Portland art exhibit opened on April 4 and here it is minutes before the online auction opens, and I am wondering about familiarity, the proverbial, and “a fictional world only slightly different from our own” (Craig Hickman describing his piece in What If ?, April 3, 2013). The exhibit prompts a questioning and a curiosity about ideas and traversing the distance between comfort of the everyday and the uncertain novelty of the unknown. Every piece here transcends the conventional, and asks the viewer to consider a different reality. It is a challenge to face familiar concepts that are rife with the expected and the known but here ignited with deviation and innovation the works become an intersection of both.

I talked to a few of the artists and designers exhibiting in the TEDx “What If ?” show to find out more….and asked them to explain a few threads woven into the body of work on exhibit that contributed to a shared ground line: that of manipulation of the human experience and layering methodology to explore the unknown. The integrative thinking and the intersectionality of this exhibit offered the opportunity to embrace the show’s portal to fascinating new representations of reality, the future, and here, and now.

The Opulent Project’s Meg Drinkwater explained “the found files that are used to create [the] ring act as symbols for what we know to be rings….By appropriating and combining these symbols…we have further emphasized the caricature that is in our collective mind….we attempt to ‘manipulate the human experience’ by examining it and questioning it.” [Look at the Opulent Project’s Digital Ring]

Sara Huston of The Last Attempt at Greatness (Sara Huston and John Paananen] and the works, Expectation 03, smtwtfs 01, and smtwtfs 02, exemplify the studio’s “exploration of subjects of progress, expectation, liminal space, categorization, perception, value and the intersection and language of art and design.” Huston and Paananen’s work boldly aims at “provoking discourse and contemplation in the viewer or user in an attempt to disrupt conventional ways of thinking, induce reflection and challenge the boundaries of what is known.” Precisely, the work of The Last Attempt at Greatness is about, as Huston elaborates, “the ‘What if?’…[it is] about getting people out of their comfort zone to look at the world in a new way.” [View their work in the auction.]

Trygve Faste, an artist/designer is showing a work called Protoform Orange Red Blue in What if? Faste’s work is “about examining the creation of objects..currently and in the future, but especially in the future.” The piece in What If? endeavors to illuminate his concept that “somehow the future will be more promising than the present.” Acrylic on canvas, Protoform is a product of “studio art and industrial design.” Faste explains that he has given himself “the challenge of trying to convey the complex relationships we have with the dynamic landscape of objects that surround us through the use of abstract painting and form….” He also believes that designers strive to “create new objects and experiences that bring together appropriate materials and technologies to create innovative solutions to everyday problems,” thus making objects of our environment; for the most part, he postulates this “comes from a place of wanting to do good.” His work “tries to tap into a collective subconscious regarding the human aspirations imbedded” in our already existing creations. A self-professed optimist, Faste relates that his work “explore[s] the unknown, particularly from the vague human desire to embark on achievements….that lead to a bright and futuristic tomorrow.” [See Protoform Orange Red Blue]

Jennifer Wall’s Parametric Ring was “birthed from a process combining 6th century BC technology (cuttlefish bone casting) with neoteric technology (3-D printing from a parametric CAD file).” Wall speaks of her “pulling from discordant technologies to produce objects,” and explains her manipulation of the human experience as one where her research analyzes “the impulse to self-identify through the objects we make.” She continues, “time and history are necessary to understand the production of new ideas, which are often a reconstruction of that which already exists.” [See Parametric Ring]

What If ? may ask more questions that it answers, and prompt you to vacillate between emotions of familiarity and strangeness, between understanding and a sense of impulsive curiosity laced with insecurity. It may encourage you to recognize innovation and image as a way to explore new ideas and venture away from the expected. Yet, while the ability to leave a level of familiarity and comfort can precipitate a sense of entering a brave new world, it is this facing of dissidence that can bring the most rewarding drive forward. As Wall explains, we need contexts like this where objects “function as tangible indicator[s] of the space between past and present.”

Owning (and wearing) objects such as those available to you in this exhibit, is to “combine the past with the present so [you] can be doubly validated in ….an aesthetic taste and decision,” says Wall and achieve a greater understanding and perhaps connection. “It is plausible that all visual aesthetics are derivatives of one another, and that new ideas lie in seeing potential patterns in the visual backlog that already exists.”

It all starts today (Wednesday), my friends, tonight at 5:30 PST to be exact, here [The Auction]. This is your opportunity to be a part of this and actually have one, or more (!) of these pieces in your possession.

“What if…?” you wait until numbers start trickling in (and up) as aficionados of art and design find their way to this place and make their bid on . . . . Wait! A work that you might want? Bidding is a strategic thing, and somehow we might be made just a bit nervous that we cannot see our competition, no paddles to raise, no leaning gaze to see where that bid came from (how dare she!?), and no jocular teasing or outright disappointment when you are outdone. And, worst yet, no bidding wars?! Yes, this is a new and different way to hold an auction, just like “What If? contains novel approaches to art and design; and we hope you enjoy it.

I have to admit, there is something to be said for bidding from the comfort of your own online location. For wherever you are, I advise you to seize the moment: being online and secretly upping the bid is so deliciously satisfying……now you can add your click, in the name of healing children and buying something more than simply relevant but also something that appreciates the chance to accept both your own “visual backlog” and a voyage away from the status quo. Doesn’t that feel good?

Artists and designers with UO affiliation in TEDx Portland What If ? are

Zach Yarrington (BFA ’11 Digital Arts)

Trygve Faste (UO Assistant Professor, Product Design Program)

Laura Vandenburgh (UO Assoc Professor)

Craig Hickman (UO Professor Digital Arts)

Sara Huston with The Last Attempt at Greatness (UO Instructor), I, II, III

Jenene Nagy (UO Management Certificate)