I’ve published three papers this summer, and I’m finally getting around to blogging about them. So, expect two more posts shortly.

My good friend Jenny McGuire and I just got our paper published in the Journal of Biogeography. I can spend a lot of time bragging on the technical details, but I understand that it’s best to push the ‘Why it’s important’ to the top of popular science posts, so here it is: We can use fossils to test whether the methods we’re using to plan for future climate change work well or not.

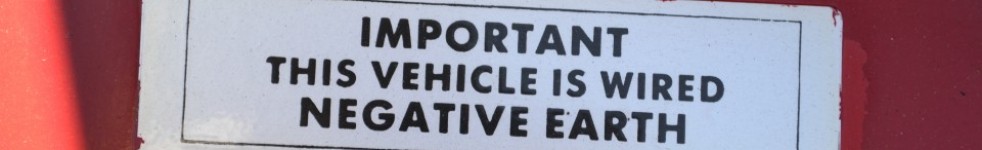

A gratuitous image of a Townsend’s vole, Microtus townsendii. Image from Wikimedia Commons by user ‘The High Fin Sperm Whale’.

Let me explain: We’re all agreed that the planet is warming at an unprecedented rate, and so we need to make plans for the future that can accommodate that warming. We also know (from the fossil record) that when climate changes, species either move their geographic ranges, evolve in place, or go extinct. The climate is changing much more rapidly than any reasonable expectations of evolution can accommodate (except for microbes!), so we’ll have to depend on range shifts to prevent extinction.

Nitpicky side note: these are range shifts, not migrations. Migrations happen cyclically, as animals move to accomodate seasons. Range shifts happen once, as a species accommodates changes in climate or other aspects of the environment.

So, range shifts right? But where will species shift? That sounds like a job for …. Science!

The current best way we have for predicting species range shifts under warmer climates is something called Ecological Niche Modelling. The fast explanation is that we measure all of the temperatures and precipitations (rainfall, snow, etc.) in areas where an animal or plant lives today and then look for those temperatures and precipitations under climate models of the future. We don’t actually know what the future will look like, but we can use several scenarios of global warming, coupled to models similar to those used to predict the weather, to come up with a suite of reasonable future climates. When all is done, we have a pretty map that shows areas where you could expect your species to be happy in, say, year 2100.

But… How do we know we’re right? Science is all about testing hypotheses, and these Niche Models are simply hypotheses. We’ll be able to test them in 2100, but by then their conservation usefullness will be past. Is there a way to test them now, you ask? Why yes, say Jenny and I: Look at the fossils.

After a lot of technical detials I’ll be happy to discuss with you in the comments, Jenny and I made hindcasts (like predictions, but backwards in time) of the ranges of several species of vole during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), the coldest time recently, around 20,000 years ago. Here are our maps:

Take home from the image: Most species were predicted well, but the two on the right were mostly wrong. What do those species have in common? Their niche models depend a great deal on precipitation, and climate models are apparently notorious poor at predicting rain and snowfall patterns.

The upshot for conservation? We can be relatively confident that our niche models are getting us in the right ballpark for future ranges, as long as the species doesn’t depend too much on precipitation for finding its ideal habitat. Additionally, Jenny and I point out that interactions between species, whether competition for resources or predator-prey interaction, could also be affecting these models’ success. In the end, the best way forward is to combine modern and fossil data to better test our conservation tools. This concept is central to the idea of Conservation Paleobiology, a field Jenny and I are pushing with our own work and outreach. My next post will be on our Conservation Paleobiogeography symposium we organized for the International Biogeography Symposium last January. Stay tuned!

Flosston Paradise! 🙂

We have a winner!

Wonderful blog post. This is absolute magic from you!

I have never seen a more wonderful post than this one.

You’ve really made my day today with this. I hope you keep this up!

제이나인 필리핀 카지노

제이나인 먹튀 링크

제이나인 보라카이 카지노

제이나인 세부 카지노

제이나인 에볼루션 카지노 가입

https://www.j9korea.com